BY LUIS ZAPATA

When the mode of the music changes, the walls of the city shake.

—Allen Ginsberg, paraphrasing Plato

ROCK ’N’ ROLL has been the soundtrack of youth rebellion for almost eight decades. It is one of the United States’ most powerful cultural exports to the world. It may seem cliché to say rock ’n’ roll is not just about music, but the moment it gripped a postwar generation of American teenagers, its anthems became words to live by—and future generations would never be the same.

Kids questioned the establishment and decided they did not need to follow parental rules and expectations. They stopped accepting the status quo, and their outside-the-box thinking contributed to accelerated technological advancement. Talented Latinx and Indigenous musicians who crossed cultural boundaries played a big role in the rise of rock ’n’ roll, and all that came with it.

When I was a teenager in the 1980s in an extremely violent Peru, rock’s metal subgenre provided some of us with shelter, pride, inspiration, and empowerment. It was one type of music that was so loud and powerful that it shielded me from the sounds of the violence going on outside in the streets. More than thirty years later, these musicians are still my heroes. But the tribal essence of Latinx in the metal lifestyle has not been understood properly by social scientists because its story has not yet been told.1

Technology: One Step Ahead of Your Parents

If country music arrived on horses and blues chugged in on trains, rock ’n’ roll came drag-racing on eight cylinders and roaring on motorcycles. But it spread via tiny transistor radios, which could be muffled under a pillow to allow clandestine listening to Wolfman Jack’s border-radio blasts, Alan “Moondog” Freed’s rock ’n’ roll dance parties out of Cleveland and New York City, and the jives of Dr. Hepcat (real name: Albert Lavada Durst) in Austin, Texas. Before the transistor, radio listening was a family affair; generations congregated around a large piece of furniture and developed musical tastes together.

I like to think that Marlon Brando gave birth to rock ’n’ roll in the 1953 movie The Wild One. When his character is asked, “Hey Johnny, what are you rebelling against?,” he answers “Whaddya got?” The more passionate, proletariat sector of 1950s youth gave birth to traditional rock culture just as the first hits of Latinx rock ’n’ roll appeared. Cuban mambo (the favorite music of zoot-suited pachucos), jump blues (loved by greasers), and African-American rhythms were combined to create the 1958 hit “Tequila,” recorded by the Champs.

Latin participation in rock ’n’ roll occurred from the beginning with Richie Valens, Chris Montez, and Little Julian Herrera (actually a Jewish Hungarian runaway adopted by a Latino family who had a No. 1 hit while impersonating a Latin rock ’n’ roll singer), as urban planning dictated home loans based on skin color, mixing Blacks, Latinx, and Jews in the same geographical areas.

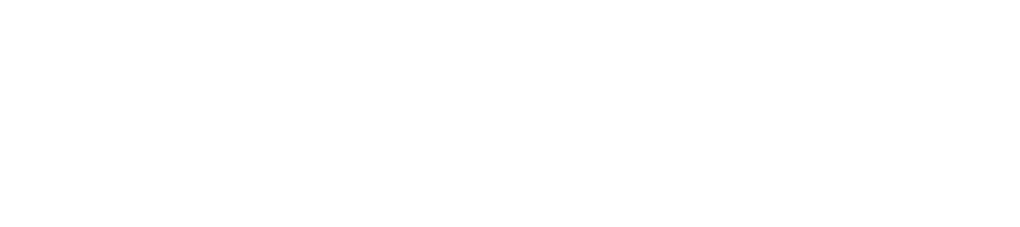

In 1958, Link Wray, a Shawnee, had a hit with “Rumble,” the only instrumental song that has ever been banned from the radio.2 E Street Band guitarist Steven Van Zandt said of its raw, angry sound, “Link Wray wrote the anthem for juvenile delinquency.” (There was no self-respecting high school cafeteria in America where at least a food fight didn’t break out when “Rumble” came up on the speakers.) The ferocity in the strumming and use of power chords, distorted signal, and driving drumming in the song would have a substantial impact on guitarists Jimmy Page, Jeff Beck, Pete Townsend, as well as Iggy Pop. This influence would be felt for generations.

In the 1960s, popular music took at least two marked directions in sound and sensibility: one was the folk-oriented “wooden” acoustic music of artists such as Bob Dylan, Richie Havens, Atahualpa Yupanqui, and Victor Jara; the other was the electric-charged sound of the British Invasion, delivered by the Beatles, the Kinks, and African-American guitar god Jimi Hendrix, who gained fame after moving to England. Hendrix, who also claimed Cherokee heritage, expanded the language of guitar and immortalized himself with the instrumental anti-war hymn “Machine Gun” and his version of “The Star-Spangled Banner,” performed at Woodstock in 1969. In both the Jimi Hendrix Experience and his Band of Gypsys, Hendrix incorporated beats reminiscent of traditional Native American drumming.

One of the British invaders’ major innovations was the notion that rock ’n’ roll no longer needed the roll; it could just rock. The distinction is later expressed in the sound of Led Zeppelin, Humble Pie, The Who, and Black Sabbath. Most rock historians credit Black Sabbath with the birth of heavy metal, characterized by dark lyrics, extremely loud, distorted guitars, and anti-establishment messages. When the band formed in Birmingham, England, that city was still in ruins from World War II. This was the new, angry, industrial sound of the people.

Let There Be Sound

Latinx and Native American musicians are present at the beginning of some very significant eras of loud rock, and have contributed to rock’s evolution. Generational renewal has kept alive a music to which critics would tend to attribute only shock value, making it a sixty-plus-year sound institution. Furthermore, metal has evolved into cultural reformulation by going against canonical establishment, finding echo in conquered populations around the world.

In the 1970s, war-painted New Yorker Ace Frehley, whose mother was Cherokee, became the quintessential heavy metal guitarist for the band KISS, selling millions of albums and tickets around the world and influencing countless loud rockers. Indigenous heritage was even more apparent in Southern hard-rock band Blackfoot, in which all but one original member had Native American blood.

Although they sold millions of records and concert tickets, heavy metal acts were heard mainly on college radio for years. Commercial radio actively avoided metal, particularly shying away from bands like WASP, led by the politically outspoken, often controversial Blackfoot Blackie Lawless. But in November of 1983, the album Mental Health, by Quiet Riot, a Los Angeles band including Cuban-born bassist Rodolfo Maximiliano Sarzo Lavieille Grande Ruiz Payret y Chaumont—aka Rudy Sarzo—and Mexican-born lead guitarist Carlos Cavazo, displaced the Police’s Synchronicity album from the No. 1 position on the Billboard Top 200 album chart, and the single “Cum on Feel the Noize” became the first heavy-metal song to reach the top five of the Billboard Hot 100. Sarzo went on to perform with Ozzy Osbourne, Whitesnake, Dio, Blue Öyster Cult, and many others.

Following Quiet Riot’s success, many metal bands came into the mainstream market, including Twisted Sister, with Nuyorican singer-guitarist Eddie Ojeda. The band scored hits with songs about teenage rebellion, which drew condemnation from then-Senate wife Tipper Gore. In a congressional hearing, vocalist Dee Snider testified brilliantly against Gore’s censorship efforts.

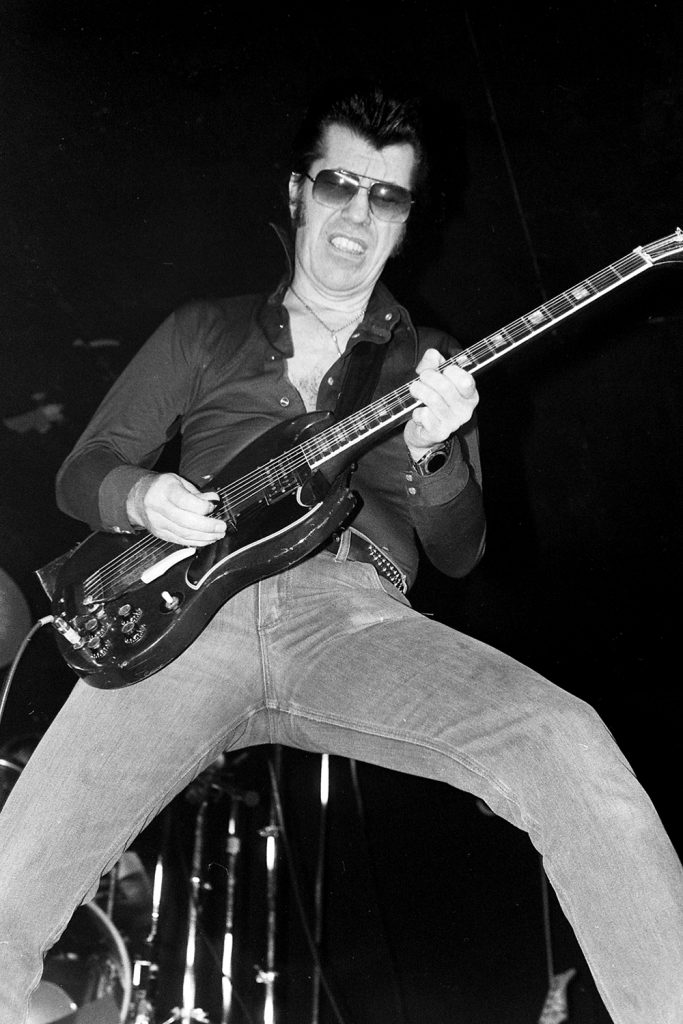

Notable Latinx metal players also include Cuban Juan Croucier, RATT’s bassist; Mexican-American Roberto Agustín Miguel Santiago Samuel Pérez de la Santa Concepción Trujillo Veracruz Bautista—aka Robert Trujillo—bassist for Suicidal Tendencies and Metallica; Bon Jovi drummer Héctor Juan Samuel “Tico” Torres, whose parents emigrated from Cuba; and Slayer’s Chilean-born bassist-vocalist Tom Araya and Cuban-born drummer Dave Lombardo.

Most of the top metal bands of the eighties, including AC/DC, Ozzy Osbourne, Whitesnake, Queen, and Iron Maiden, played Rock in Rio, one of the largest rock festivals in history, which debuted in 1985 as a ten-day event for which an entire City of Rock was built just outside of Rio de Janeiro. It attracted 1.5 million attendees, and has since been held in Lisbon, Madrid, and Las Vegas. Iron Maiden, Scorpions, Megadeth, and Sepultura (founded by Brazilian brothers Max and Igor Cavalera) will all headline at Rock in Rio VIII in fall 2019.

Louder Than Hell

As a kid in Peru, I already loved the Beatles and Santana, Teen Tops, and others. But I felt I needed something wilder, louder, faster, meaner than that. I hoped that this type of music existed somewhere but certainly it did not on the airwaves of a nationalist military government. And then my mother bought me KISS’s Alive!—the double live album. I was ten years old. That was the sound. Older kids hated KISS. You fought for their honor in the schoolyard. They prepared you for what was going to come up later on in life.

One of the most politically outspoken and influential bands in the world, Rage Against the Machine, fronted by Mexican-American vocalist Zack de la Rocha, was known for mixing rap and metal, and for supporting political efforts such as the Salvadoran Frente Farabundo Martí para la Liberación Nacional (FMLN).

In their most extreme expressions, death and black metal embrace more radical subjects and social commentary. Mexican death-metal band Brujería, formed in 1989, originally included Dino Cazares, Raymond Herrera, and Jello Biafra; Cazares and Herrera later formed Fear Factory. Brujería’s members use nicknames and sing about Satanism, sex, and drug trafficking. Tampa, Florida, developed a strong death-metal scene in the mid-eighties with iconic bands Cannibal Corpse, Deicide, and Morbid Angel. Salvadoran-born drummer Pete Sandoval of Terrorizer and Morbid Angel is known as “the father of blast beat”—a rapid-fire drumming style played with two bass drums, reminiscent of a semi-automatic weapon. It’s the signature beat of death- and black-metal bands.

Black metal likely began in New Castle, England, with Venom, an openly anti-Christian outfit, and was adopted by Scandinavian kids disgusted with the Catholic church’s pedophilia scandal. Similar philosophies have taken root in Latin American and Native American metal scenes, giving rise to the Indigenous black metal and “Rez metal” genres. Heard mostly on Navajo reservations, Rez metal is an angry and dark, yet powerful, expression of longing for cultural respect and survival. (As I write this, I am listening to the late drummer Randy Castillo, whose parents were Chickasaw; he played with Ozzy Osbourne, Lita Ford, Motley Crüe, and other heavy-metal icons.)

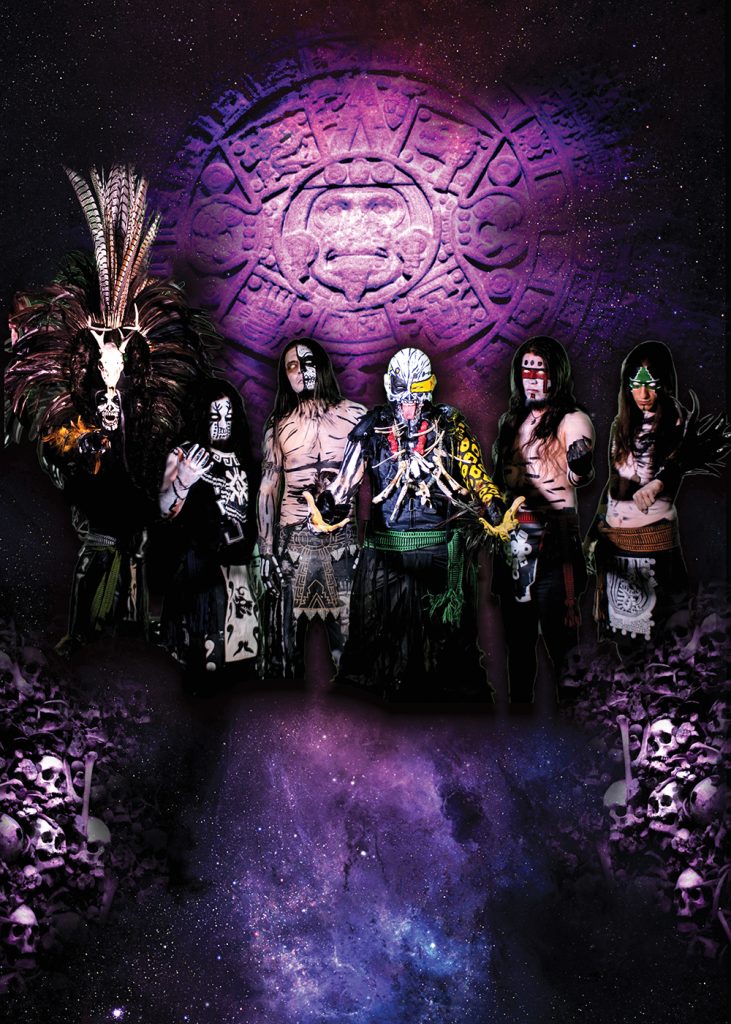

The most successful Indigenous metal band is Cemican, from Guadalajara. Cemican means “all the life” in Nahuatl, the language of the Aztecs, spoken today by over 2 million people. (“Indigenous” refers to the subgenre of metal, not the musicians’ ethnicity.) Using pre-Columbian instruments and Nahuatl names and lyrics, they have played the world’s biggest metal festivals, including France’s Hell Fest and Germany’s Wacken Open Air.

In a historical sense, metal and punk remain the most extreme cultural variations of rock. I would even venture that just as African Americans have preserved Gospel through various genres, including rock ’n’ roll, Native Americans are protecting some of their traditions using hard rock. Rudy Sarzo and Carlos Cavazo moved metal from underground to mainstream, and gave fuel to metal capitals like San Antonio and Los Angeles. Rock ’n’ roll has attended its own funeral at least four times that I am aware of. And in all those times, what saved the music and kept the flame alive were the loud rockers. The ones with the warrior mentality. Latinx and Native American musicians contributed to the innovation of the time. And I am happy to help tell their story.

Luis Zapata was born in Lima, Peru. He earned his bachelor’s and master’s degrees from The University of Texas at Austin. Working in the music industry since 1994, Luis spent time at record labels, ranging from blues to metal. He introduced Rock en Español to Central Texas, creating the Latino Rock Alliance. He owns specialeventslive.com, which entertains over half-a-million people in the Texas Hill Country yearly. He welcomes any comments at rocklectures.com.

Notes

- José Ignacio López Ramírez Gaston and Giuseppe Risica Carella, Espíritu del metal. La Conformación de la Escena Metalera Peruana (1981–1992) (Sonidos Latentes, 2018).

- George Lipsitz, “Cruising around the Historical Bloc: Postmodernism and Popular Music in East Los Angeles,” Cultural Critique, no. 5, Modernity and Modernism, Postmodernity and Postmodernism (Winter 1986–1987): 157–77.

Legendary rock guitarist Link Wray performs at The Showplace in Dover, NJ, November 1978.

KISS receives its star on the Hollywood Walk of Fame. From left: Ace Frehley, Paul Stanley, Peter Criss, and Gene Simmons.

Twisted Sister in concert. From left: Jay Jay French, Eddie Ojeda, and Mark “The Animal” Mendoza.

Metallica bassist Robert Trujillo.

Randy Castillo.

Rudy Sarzo at the God Bless Ozzy Osbourne premiere (2011).

Cemican. From left: Xaman Ek (rituals, dance, pre-Columbian instruments), Mazatecpatl (pre-Columbian instruments), Tecuhtli

(guitar/vocals), Tlipoca (drums), Ocelot (bass/backing vocals), and Yei Tochtli (pre-Columbian instruments). Costumes are interpretive.