BY BEATRIZ BUSTOS

CHILE is a country commonly known for its turbulent political past and its economic achievements over the last twenty years. Neoliberal policies such as privatization and deregulation have been implemented there under the premise that open and free access to global markets through commodity exports will lead the country to development. The result of these policies looks promising. As reported by the Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD), Chile’s macroeconomic indicators are in some regards comparable with those of other industrialized countries, and the government actively promotes industries of the extractive economy as key for foreign investment.

Historically known for its copper, Chile today continues as a global leader in copper production, and is the top global fruit exporter from the southern hemisphere. Chile is also among the top ten producers of wood and fish, particularly salmon. Yet the ecological and social effects of this export-oriented strategy are at the core of recent social upheaval that is challenging the country’s democratic present. A case that illustrates these tensions, and the effects on rural livelihoods, is the salmon industry in the Los Lagos region.

Chilean Salmon in the World

Salmon is Chile’s fifth main export, and Chile ranks second in the world for salmon production after Norway, with its fish reaching markets in Japan, Europe, and the United States. The three types of salmon produced in Chile—Atlantic, coho, and trout—were introduced by a public-private partnership that has transformed the regional economies of Los Lagos, Aysén, and Magallanes in the south of the country. When the industry started forty years ago, salmon did not exist in the wild, yet it was argued that the country was a paradise for salmon due to the existence of ecosystemic conditions required to foster production, as well as the availability of cheap labor.

The evolution of the salmon industry in Chile is nothing short of revolutionary. In less than twenty years, it took over the Los Lagos region and moved from being an industry of 100 percent small, national firms, to a concentration of fewer than thirty firms with important transnational capital presence from Norway, Japan, and the United States. The creation of this industry required labor and technology, and transformed whole landscapes in service of the production of one commodity. These territorial transformations, in turn, affected other activities, such as artisanal fisheries, mussel growing, and subsistence agriculture, and their ecosystems.

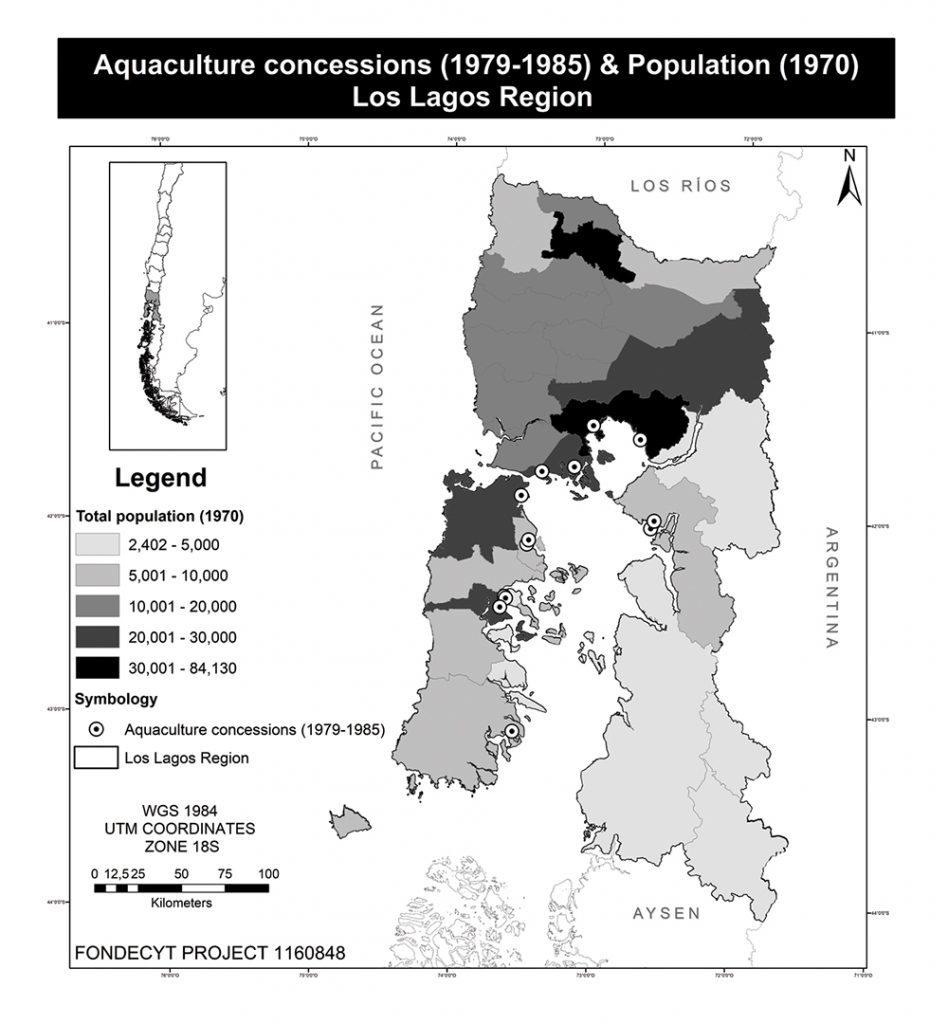

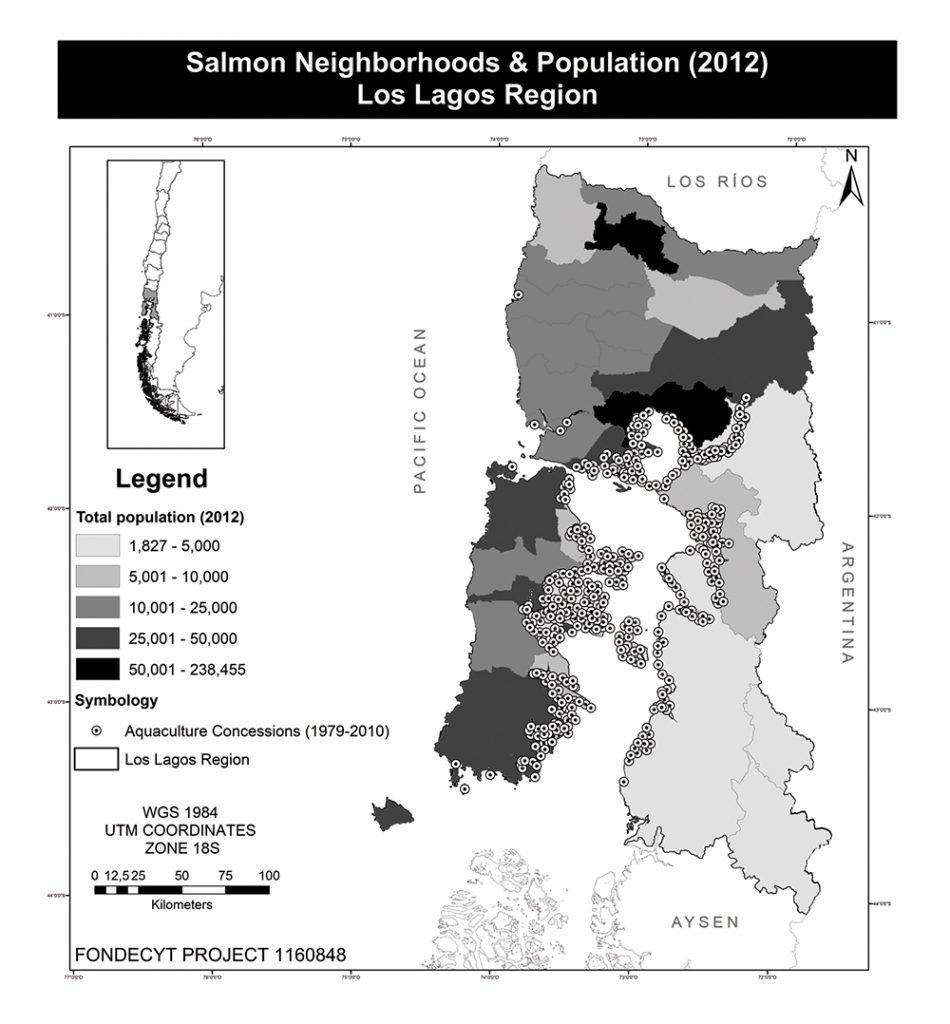

The pair of maps below show how the landscape of Los Lagos was transformed due to the influence and actions of the salmon industry. Specifically, they illustrate the evolution of salmon concessions and the way in which they took over the territory—both marine and terrestrial—of Los Lagos. As the industry became the main economic activity of the region, important cultural and social transformations took place as well: increased intra-regional migration, explosive and unplanned development of urban centers, concentration of services in the regional capital, the introduction of credit and wage salaries to the lower-income segment of the rural population, and, importantly, a redirection of state policies toward strengthening the industry as opposed to keeping it in check. To sum up, Los Lagos became richer in material terms, but the distribution of that wealth, and its long-term impact, is a subject of public debate.

Is Bigger Always Better? The Salmon Industry’s Effects on Local Communities

The industry has been quick to frame its presence and expansion in the region in terms that evoke modernization. In interviews, industry representatives convey a sense of accomplishment, pride, and the self-image of pioneers who have made a heroic gesture. Most of them are college graduates from other cities who came to Los Lagos to work for the industry and stayed. Their pride is based on the sense that they have built a global industry from scratch, with ingenuity and hard work. As opposed to the copper industry—which has always been there—salmon was made to work by these professionals. The narrative thus dismisses pre-existing economies and activities as “nonproductive,” “rural,” and “folkloric,” while salmon brought the modern world to the region.

On the other hand, for the communities of the region, the story is much more nuanced. People voice a sense of spatial disruption, of invasion and expulsion, but also of inevitability. In short, rural inhabitants wanted and embraced the promise of modernization brought by the salmon industry, the access to material well-being associated with contract jobs, the construction of public infrastructure needed to host a larger population.

More interestingly, the salmon industry fit well with preexisting economic practices in the region. For example, there is the notion of “fevers” that is used to explain historically local economic cycles: Locals were used to moving from one nature-based commodity to the next, and were at ease with the flexibility this entailed. The abundance of nature meant there was always something new to move to after the last bust. The salmon industry took the idea of farming, with its cycles of sowing and harvest, from the agricultural tradition. Artisanal fisheries contributed the understanding of currents and sea life involved in salmon production. Yet the industry transformed local mobility practices by creating conditions for locals to stay in one job and one place. This was considered both a cost and a benefit: more women were able to enter the labor force; men were able to stay home, changing gender dynamics; and the consistent paycheck at the end of the month allowed people access to material goods, while they stopped relying on community work for help.

Since its origins, the salmon industry has periodically suffered environmental problems. The first recorded algae bloom to affect the industry occurred in 1988. Since then, there has been a steady increase in the presence of pathogens in both the fish and the waters they inhabit. During the first decade of the new millennium, several salmon escape events caused health and ecological concerns. But the decade ended with the biggest crisis to date—outbreaks of the infectious salmon anemia (ISA) virus (2008–2010), which caused nearly 50 percent mortality in fish farms and significant financial losses, triggering new regulations and industry restructuring.

Spatial and Ecological Fixes for the Chilean Salmon Industry

New regulations implemented in 2010 were aimed at addressing the main effects of the ISA crisis, but not its root causes. As such, their purpose was to organize and coordinate production to achieve containment in case of a new outbreak. This translated into three spatial fixes—that is, solutions addressing the spatial challenges created by the industry’s mode of production: first, the freezing of aquaculture concessions in the Los Lagos region to secure control of existing producers and manage the level of production; second, the establishment of aquaculture “neighborhoods” that would force coordination among producers in the same group of concessions; third, authorization of farming concessions in the southern regions of Aysén and Magallanes.

Ecologically, the fixes involved two levels. At the level of the fish, the measures aimed to prevent salmon from catching diseases by establishing lower density levels per farm, implementing health management practices that included the use of antibiotics, and introducing genetic modifications to increase salmon resistance. At the level of the ecosystem, the regulations called for mandatory rest periods during the growth stage after each harvest to allow time for ecosystems to recover, and for a mandatory shift of the pisciculture stage to closed pool systems. Currently, firms are exploring offshore and land-based growing stages to minimize the ecological impact on the sea.

Despite the institutional changes that were implemented to address the crises, the ecological contradictions associated with salmon production remain. This is because the purpose of the reforms was to secure the continuity of the industry and not to mitigate its ecological impact. This is important because spatial and ecological solutions are deeply connected in the building of a landscape of accumulation that replicates more traditional extractive industries, such as mining.

Which is why when, in 2016, an algae bloom occurred, the industry once again faced significant losses (85,000 tons of salmon died, causing net losses over $US100 million). The 2016 algae bloom was actually two consecutive events: the first, in January–February, killed the salmon; the second, in March–April, was a more familiar and frequent algae known as red tide. This one affected fishermen because the government responded with a prohibition against fishing and shellfish harvesting.

Community reaction was fierce. Fishing communities held the government and the salmon industry responsible for the disasters, blaming the unusual power and spread of the red tide on mismanagement of salmon mortalities from the first event, in the coastal area of the Chiloé archipelago. During eighteen days, community members led massive protests, limiting access to the main island of Chiloé and causing public disruption. The grievances at the core of the protests centered on the way in which the industry and the state have interacted with this territory.

Challenges Moving Forward

In the ten years between the ISA and the algae bloom crises, the Chilean salmon industry focused on spatial remedies in order to continue production, but the ecological ramifications of the industry continue to be an obstacle, and policy responses from the state have increased social unrest against the industry and the government. As such, there is a need for sustainable and sound policies that integrate economic and environmental considerations into a coherent, locally based development project.

Beatriz Bustos is a professor in the Department of Geography within the School of Architecture and Urbanism, Universidad de Chile. Her research focuses on rural development, political ecology, and economic geography. As Tinker Visiting Professor during fall 2018, she taught the graduate seminar Political Ecology and the Geography of Commodities.