By CINDIA ARANGO LÓPEZ

EL PEÑOL AND GUATAPÉ are two towns in the mountains of the central Colombian Andes, in the Eastern Antioquia region. In the early 1960s, their inhabitants never thought they would have to migrate through the water with their belongings and stories on their backs. Generations of residents, primarily peasants, had spent more than 200 years in these same territories. Then, from one moment to the next, their life projects, territorial anchorages, and identities were disrupted by the construction in the 1970s of the Guatapé dam and the creation of an artificial body of water. Decades of history and roots were completely shaken in the span of a few years.

In the history of Latin America, the generation of hydroelectric energy and the commercialization of water resources have come to represent a means of land and natural resource grabbing. This has taken place under the prevailing model of economic development promoted since 1960. Water is perhaps the most debated nonrenewable resource on current global political agendas. At the same time, the demand for alternatives to biofuels and hydroelectric plants seems to be on a slower path.

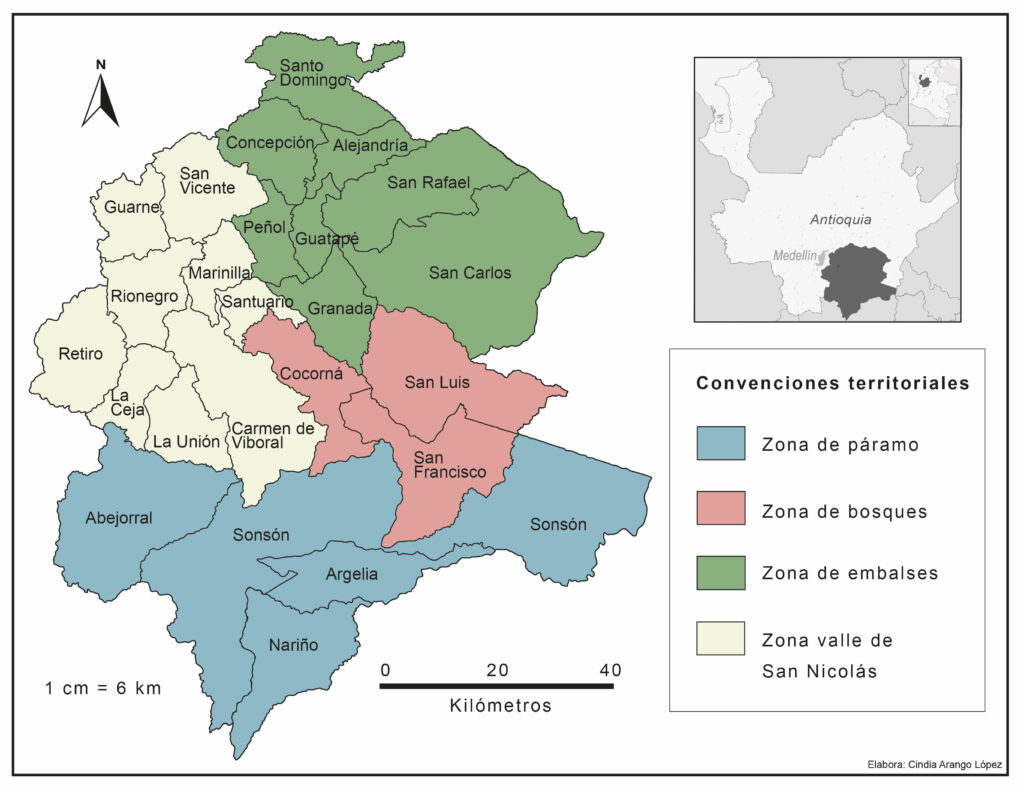

The inhabitants of El Peñol and Guatapé bore witness to a hydroelectric project that was presented in 1970 as the most significant development initiative for the Department of Antioquia and Colombia as a whole. The construction of the Guatapé dam in Eastern Antioquia allows us to understand the implications of the debate on water amid development projects (see Eastern Antioquia map). In addition, it makes evident the social, territorial, and cultural repercussions of infrastructure projects in rural communities.

Water Shortage and the Search for a Regional Solution

Colombian engineers have noted the hydroelectric potential of Eastern Antioquia since 1920, in particular the town center of El Peñol and rural areas of Guatapé, San Carlos, and San Rafael municipalities (area identified in green on map). Since 1930, the population growth in Medellín that accompanied the city’s period of urbanization and industrialization led to the widespread assumption that it would be necessary to look for drinking water beyond the city itself. Indeed, in the 1930s, an article was published in the newspaper El Zócalo with the headline “Medellín morirá de sed dentro de 50 años. Hay que salir del Valle de Aburrá” (Medellín Will Die of Thirst within 50 Years; We Must Leave the Aburrá Valley). One of Medellín’s closest subregions is Eastern Antioquia, at a distance of approximately 30 kilometers (about 18 miles). This prelude opened the door for engineers and technicians from the city to consider the importance of seeking alternative sources of potable water nearby.

In response, in 1955 the Public Companies of Medellín (Empresas Públicas de Medellín, EPM) was established in Antioquia as an autonomous provider of essential residential services such as water, telephone, and electricity. Locally, EPM is regarded as perhaps the best public utility company in Latin America. With its foundation, the company promoted the need to expand the city’s water supply. The first technical and inspection studies to explore a major hydroelectric project at Guatapé began between 1960 and 1963. This meant significant growth for EPM.

These studies were carried out in the urban area of El Peñol and rural areas of Guatapé due to their proximity to the Negro-Nare River, which flows into the Magdalena River. Between 1963 and 1970, the project was developed and proposed on a technical level, yet the impact on the local community remained unclear. In response, residents organized in opposition, realizing that an infrastructure project of this magnitude would reach the doors of their houses and the very boundaries of their properties without considering them. In particular, the inhabitants of El Peñol were facing the physical disappearance of their town and their own possible forced resettlement.

Meanwhile, EPM applied for loans from the International Bank for Reconstruction and Development, currently known as the World Bank. In contrast, the community of El Peñol organized massively to confront the project and prevent its installation. Their collective efforts bore fruit in 1969, when a document known as the Contrato Maestro was signed between EPM and the municipality of El Peñol on behalf of its inhabitants. In the document, 95 clauses were drafted that sought to mitigate the impact of resettlement and consider social readjustments for the population. The technical studies continued to advance, accompanied at the same time by the construction of houses on a new piece of land at a distance of approximately 57 kilometers (about 35 miles), also in Eastern Antioquia. Although some rural portions of Guatapé were flooded, its urban center was preserved. Currently, it is a town with a scenic pier in facing the great dam. In contrast, the new settlement of El Peñol was built on a mountainside, facing away from the dam.

Both processes were traumatic for the population. On the one hand, EPM began gradually violating the agreements made in the Contrato Maestro, including the pledge to build new homes that were like the originals. On the other hand, the residents of El Peñol had to decide whether to leave or to stay while the water rose to their ankles. Leaving meant carrying their territory on their backs—the dynamic space comprised of memories, practices, traditions, and the past.

Creation of a Reservoir, Destruction of a Town

El Peñol was built on the banks of the Negro-Nare River, giving its inhabitants easy access to water. Founded in the eighteenth century, it began as an Indigenous town, focused on growing corn, potatoes, beans, and carrots. The area’s inhabitants used the river for fishing, irrigation of crops, and for daily tasks such as washing clothes or transportation.

The sight of the peaceful river flowing by the central park in El Peñol changed with the flooding of the reservoir, which began in 1970 and culminated in April 1979. The river eventually engulfed the park and grew until it became a mirror-like body of motionless water. Resettlement activities included the exhumation of approximately 1,100 corpses from the cemetery of El Peñol, the disintegration of family nuclei, and selection of families who would populate the new settlement. The peculiarity of excluding single residents, including widows and widowers, was integral to the new social composition of El Nuevo Peñol. The resettlement process meant the forced forgetting of collaborative networks that were anchored to a traditional space. It meant adapting to the new urban plan, as the old town, built on a Roman grid, surrounded by the river’s waters, with crops on its slopes, was replaced by a new settlement with urban lines and tiny, homogeneous houses that did not meet the needs of large families so common in Antioquia.

The artificial body of water has partially reconfigured the vocation of El Peñol from an agricultural town to one focused on tourism. The reactivation of the agricultural sector in the rural portions of El Nuevo Peñol took years to achieve, and the promotion of new crops and their insertion into the regional market is still an ongoing process. Meanwhile, the urban center of Guatapé faces the dam, featuring varied gastronomic offerings and recreational activities for residents and visitors. At the same time, the dam continues to generate power in Antioquia and other parts of Colombia.

This entire process can be understood as a spatial and economic rearrangement influenced by the commercialization of water, a project carried out in the name of development that ignored and all but erased community ties. Even today, some ruins of El Peñol emerge from the water, like the cross of the main church, currently a reference point for religious and sporting events. Many memories still survive among those who lived in El Viejo Peñol, as the town that came to rest under the water is known. However, the inhabitants’ collective ties are among the most palpable traditions from the past.

The social organization among inhabitants of El Peñol during the 1960s was significant for Eastern Antioquia as a region. According to the National Center for Historical Memory, Eastern Antioquia was the industrial and commercial hub of Antioquia, an area where one-third of the country’s energy generation would be concentrated. Many leaders of El Peñol, as well as community members, opposed the dam proposal. Although it was impossible to stop the project, the Contrato Maestro included the first guidelines for human resettlement in Colombia. The 1970s and early 1980s saw the establishment of the Civic Movement of Eastern Antioquia (Movimiento Cívico del Oriente Antioqueño), which included leaders from El Peñol and other municipalities, such as Marinilla, and was mainly motivated by the high price of energy. Paradoxically, EPM and the government displaced an entire town to build a hydroelectric dam, yet residents of the territory ended up paying for the most expensive energy services in the country.

Local and subregional residents organized a series of strikes and protests in 1982 and 1984 during one of the most critical periods of social protest in twentieth-century Eastern Antioquia. On December 30, 1989, one of the leaders of the Civic Movement, Ramón Emilio Arcila, was assassinated in Marinilla, a few kilometers from El Peñol. With his murder, the paths of protest were closed, and the future of natural resource exploitation and its impact on the population remains uncertain.

In Eastern Antioquia, there is a proud memory of the social movements of the 1960s through the 1980s, which led many Colombians to realize that the development of territories should be mediated by awareness of the resources we have, but also by the active participation of people who reside in these territories. Water continues to be in the eye of the hurricane because Eastern Antioquia remains a waterpower for Colombia. The question is whether Colombia will continue with the same model of water development or if it will be inspired by new social movements to build alternative models.

The Meaning of Water

According to the World Bank, Colombia is rich in water resources, but this wealth does not reach all Colombians equally. Water administration in the country follows environmental policies that could be considered obsolete within the framework of sustainability. Hydroelectric projects have put entire communities at risk of disappearing, a lesson that continues to be relevant. Such is the current case of the Hidroituango dam, also in Antioquia. In recent years, this project has displaced more than 500 inhabitants and put hundreds of families at risk. A hearing on April 27, 2013, in the Congress of the Republic corroborated this violation of international humanitarian law. Thus, the case of the resettlement of El Peñol is not an isolated experience. On the contrary, infrastructure projects and the unsustainable use of natural resources continue to impose themselves on many Colombians.

It could be said that a population traditionally dedicated to smallholding-type agriculture was seriously disrupted by new, unprecedented vocations such as tourism and the water trade, all a result of the dam’s creation. The inhabitants of El Peñol had to relocate and reinvent themselves in view of hydroelectric development projects, which continue in the region. They had to adapt by creating new collective spaces and assume that the water that had accompanied them daily—for fishing, for irrigation, and for transportation—had also changed. Water now represents electrical energy for many Colombians in the central Andes. It also represents nautical tourism. It would be pertinent to observe how a resource can have multiple meanings and at the same time completely transform an entire town, disappearing or reinventing it. ✹

Cindia Arango López is a LLILAS doctoral student from Colombia whose research interests include environmental history, human geography, identity, and race.

References

Centro Nacional de Memoria Histórica. 2022. El resurgir del Movimiento cívico del Oriente antioqueño. January 14.

Flórez, Antonio. 2003. Colombia: evolución de sus relieve y modelados. Bogotá: Universidad Nacional de Colombia.

Franco Giraldo, Dana María. 2021. Incidencia del desarraigo en el uso y apropiación de los espacios públicos en el municipio de El Peñol. Graduate thesis presented for the title of Professional in Territorial Development, Universidad de Antioquia, Oriente campus.

García, Clara Inés. 2007. “Conflicto, discursos y reconfiguración regional. El oriente antioqueño: de la Violencia de los cincuenta al Laboratorio de Paz.” Presented at Primer Seminario Nacional Odecofi, Bogotá, March.

INER. 2000. Oriente. Desarrollo regional: una tarea común universidad-región. Medellín.

López D., Juan Carlos. 2009. “El atardecer de la modernización: La historia del megaproyecto hídrico GUATAPÉ-PEÑOL en el noroccidente colombiano, años 1960/1970.” Ecos de Economía 13 (28).

Sánchez Ayala, Luis, and Cindia Arango López. 2016. Geografías de la movilidad. Perspectivas desde Colombia. Bogotá: Universidad de los Andes.