By RODRIGO SALIDO MOULINIÉ

Historian Mauricio Tenorio Trillo was the opening keynote speaker at the 2022 Lozano Long Conference, “Archiving Objects of Knowledge with Latin American Perspectives,” an interdisciplinary online conference organized by Associate Professor Lina Del Castillo and hosted by LLILAS Benson in honor of the centennial of the Nettie Lee Benson Latin American Collection. This reflection on Tenorio’s work and thought was originally published in Not Even Past, a digital magazine of the Department of History at The University of Texas at Austin. View Tenorio’s keynote.

MAURICIO TENORIO THINKS WITH HIS FEET. As his soles touch the asphalt, he feels a piece of one of his dearest obsessions: the city. Not Mexico City specifically, although it might be the one he feels closest to, but the idea of the city. Cities have so much to say. A street in Barcelona, an old building in Chicago, an awkward monument in Washington, DC, a park in Berlin: they all have stories and a history. And Tenorio, a professor of history at the University of Chicago and profesor asociado at the Centro de Investigación y Docencia Económicas, Mexico City, tells these stories through his work.

I like to repeat one about a hidden monument in Mexico City. Inside the column of the Independence monument, the capital’s famous postcard-ready landmark with angel’s wings, the white statue of an obscure figure guards the ashes of Mexico’s founding fathers—a monument of a seventeenth-century Irishman. Tenorio tells the story of Guillerme de Lampart, the “Irish Zorro” who plotted an independence movement with religious undertones in the 1640s: a peculiar reading of the Bible led him to believe that Spain did not have sovereign rights over the Americas. He became a controversial figure in Mexican history. The Inquisition burned Lampart in 1650, making him a martyr for anti-Church Porfirian liberals. Placing his monument publicly would have surely triggered heated historiographical and political debates, weakening the process of national reconciliation. Thus, Lampart made his way into one of the nation’s central monuments discretely.1 Yet Tenorio’s driving curiosity lies elsewhere: it is not so much about what cities have to say, but how they say it. The location and concealment of Lampart’s monument suggest broader discussions on religion and independence, heroes and martyrs, history and the city. Tenorio explores how cities dictate these stories.

He also walks exactly the way he thinks: long strolls with scattered stops to contemplate a door, a monument, or a hallway; sudden excursions to renovated neighborhoods, abandoned places, and streets with dead ends. He wanders through these cities without a fixed route, yet always with some purpose—the walks become essays. I remember he once told me to meet him on the outskirts of Mexico City. Eight o’clock, sharp. “Let’s take a walk,” he said. What I expected to be a stroll around the block became a two-hour march to a coffee shop in La Condesa. “I’m writing a book about walking,” he told me. I failed to realize what he meant: he was right there, at that moment, writing. Reading and writing, Tenorio argues, are not simultaneous acts; but walking, reading, and writing are. “Because while we think the urban text we write it, we paraphrase it, we correct it. To walk a sentence is to write it.”2 The embodied experience of walking through cities intertwines the three acts. I witnessed how walks twin words and steps, language and history, body and consciousness. If they are not the same things, they are at least made from the same thing.

I first met Tenorio in 2017 during a talk in Chimalistac, Mexico City. He presented a paper on the concept of peace—an ugly, dirty, and corrupt business yet an indispensable one, he argued—and its implications in history. Exploring the peace after 1876 and dissecting what it was made of yielded two troubling conclusions: (1) War and decreed forgetting, not ideas or agreements, brought peace. (2) War crawls back in when its horrors vanish in the name of desecrating the dirty business of peace. Memory has an expiration date.3 After the talk, my mentor, Fernando Escalante, introduced us and asked if I would be interested in editing one of Professor Tenorio’s manuscripts. I then started working on the manuscript of La paz: 1876, a book that deeply influenced me. It worked, along with others, to steer me away from political science and drive me to history.4

“I am, first and foremost, a reader,” Tenorio replies when asked how he became a historian, “a reader that succumbs to the temptation of writing.” He blows the smoke of his cigar. After obtaining a degree in sociology from the Universidad Autónoma Metropolitana, he went to Stanford and had a rough start. He landed in California’s eye of an ongoing storm: the “culture wars” of the 1990s, or, as Tenorio calls it, the moment of the “post-this and post-that.”5 Learning the English language in those years entailed, for him, an effort in ventriloquism. It was a craft he had mastered in Spanish before: language not only as a means to communicate, but as performance. It seemed like mastering a discourse was more than a means to acquire knowledge, it was knowledge itself. To overcome it, to outgrow the puppet that can only speak about the tip of the iceberg, he started over. “Throw away the puppet and remain silent,” he wrote. “That’s what libraries are for.”6

Discarding the puppet meant finding a new voice, a learned English that works as our current Latin. And it worked. English-writing became something like a turbo engine, a style that demands clarity, structure, getting to the point quickly. Like a good soccer referee, the writer should become unnoticeable. But it is not a mirror of his voice in Spanish, where ironies, digressions, and quotes from his favorite boleros stand in the way. These obstacles make the writing richer, more interesting, honest, humorous, yet still different. They are experiments rather than expositions. For instance, a month after Mexican artist Juan Gabriel (known as Juanga) died in 2016, Tenorio published a beautiful, personal eulogy in Nexos.7 Intertwining song lyrics, memories, sociological and historical analyses, the essay embraces Juanga’s complexity and importance for the nation, but it also shows how indispensable Juanga was for Tenorio. For a moment, I thought an expanded version of the text would be a great fit for the Music Matters series of UT Press, a Why Juan Gabriel Matters. But the project crumbled the moment I went back to the essay and tried to imagine it in English. From the first line, “Quien esto escribe es un cursi,” I knew the idea was doomed to fail. That something that gets lost in translation is precisely the thing Tenorio seeks to communicate.

Tenorio’s life work thus resists translation and a clear-cut division regarding language. As with many multilingual academic writers, not only do the topics and types of publication differ between English and his native tongue, they are also separate tracks of thought. These tracks clashed recently in two published books. In Latin America: The Allure and Power of an Idea, Tenorio traces the origins of the idea of “Latin America” and not Latinoamérica, which is a different thing. The term feels more at home in English, and, against Tenorio’s prediction that the concept would vanish along with racial theory, it will not go anywhere in the near future. As a teaching engine, as a category used by consultants and regional experts clinging to the existence of their imagined region, as an identity marker for academic studies, or as a pristine border between north and south, “Latin America” will endure. Tenorio proposes, then, to use its power against it: to keep it as a moving target for critique, exploration, and reinvention. Every attempt to destroy it builds something new.8 The second book makes the clash more explicit. Clio’s Laws collects a series of essays written originally in Spanish. While these texts remain untranslatable for Tenorio, the project inspired both hope and terror in him—an experiment he could not refuse. Reviewers will say whether Tenorio’s voice in Spanish, the rusticity and playfulness of his erudite prose, makes its way into the translation. I believe it does, as it did in the popular music chapter of his Latin America, but I’ve read both tracks. Perhaps that judgment is forbidden to me, too.

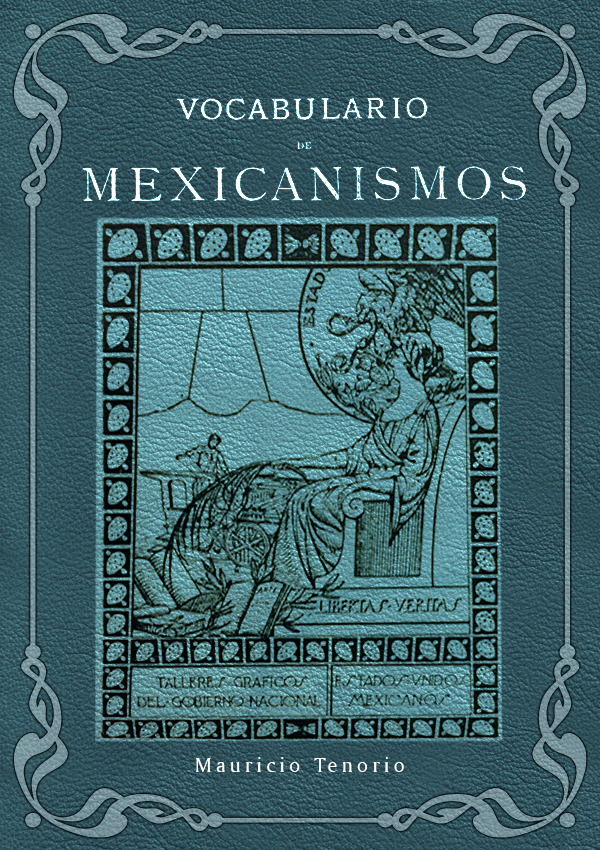

Far from those crossroads, Tenorio started another untranslatable online project, an experiment in philology: his Vocabulario de mexicanismos.9 The challenge of describing it here lies not only in the words he explores—amarchantarse, apapachar, achicopalarse, mamón, naco—but also in the shape of the entries. They do not read like definitions, etymologies, or explanations. The Vocabulario elucidates and elicits meaning by weaving in with anecdotes, memories, homages. The entries read like essays, like walks through the words. For instance, and I hope he will forgive me, the entry on achicopalarse begins:

The Diccionario de la Real Academia Española—which doesn’t bother to define Indian things—considers “achicopalarse” a Mexican and Central American word that plainly means “to shrink.” Nothing more. Since the word is not theirs, they do not feel it, that is enough for academics. For don Joaquín García Icazbalceta, however, the word meant much more: “to swoop, to be discouraged, to be excessively saddened, may apply to animals and even plants” (Vocabulario de mejicanismos, 1899).10

As I translate those words, the riddle and journey they tried to evoke disappear. I write them down to navigate the blurred yet still real boundary that separates these two tracks of thought, these styles of thinking and putting it on paper. Too many words in italics are usually a sign of trouble.

Beyond the concrete histories and arguments Tenorio makes in his books, the bulk of his work offers broader lessons on the worlds between history and language. While he feels uncomfortable with the label of global history, his work crosses national boundaries because the subjects demand it. The city, the nation, world fairs, war, and language, they are all objects scattered across place and time. This more-than-national approach allows some apparently impossible mergers: Mexico City and Washington, DC, at the turn of the twentieth century; the myths of Buenos Aires and Mexican legends; Brazilian, Spanish, and American histories. But it also exacts knowing these histories and showing their specificity. Things do not care to fit in methods or frameworks. And to follow them rigorously, one needs to become more-than-national.

Perhaps it is late for disclaimers, but foolish honesty prevails. I tried to write an overview of Tenorio’s work, an introduction. Against my better judgment, however, I ended up implicating myself and wrote something closer to what philologist Antonio Alatorre called estampas: imprints or vignettes of a shared story.11 The student defeated the professional reviewer in me. Not because my personal experience matters in any way to showcase the rigor, scope, and importance of Tenorio’s work, but because of an endemic problem that I am not the first to encounter: when we write about our teachers, we are always writing about ourselves. ✹

Rodrigo Salido Moulinié writes, photographs, and is a doctoral student in history at The University of Texas at Austin, where he is a Fulbright–García Robles Scholar and a Contex Doctoral Fellow. His first book, El pasado que me espera: bosquejo de etnografía cinemática (Mexico City: Bonilla Artigas, in press), explores the politics and poetics of ethnographic representations of religious beliefs in the case of Santa Muerte.

Editor’s note: Mauricio Tenorio was interviewed in Spanish for the podcast series celebrating the Benson Centennial. Escucha: Entrevista con Mauricio Tenorio

Notes

1. Mauricio Tenorio Trillo, I Speak of the City: Mexico at the Turn of the Twentieth Century (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2012), 22–24.

2. Mauricio Tenorio Trillo, A flor de pie (Xalapa: Univ. Veracruzana, 2020), 19.

3. Tenorio attributes this conclusion to one of the Laws of History he once transcribed. Herodes’ Law: “In history, everything turns out badly in the long run.” Evil comes, it is just a matter of time. See “The Laws of History,” in Tenorio, Clio’s Laws: On History and Language (Austin: University of Texas Press, 2019).

4. Mauricio Tenorio Trillo, La paz: 1876 (Mexico: Fondo de Cultura Económica, 2018). Fernando Escalante tried to steer me away from political science à l’américaine months before that morning in Chimalistac, but my stubbornness prevailed. I thank him here for letting me take my own crooked road.

5. “Llegar a saber,” in his book Culturas y memoria: manual para ser historiador (México: Tusquets, 2012).

6. Ibid., 40.

7. “Juanga,” Nexos, October 1, 2016. Tenorio contributes regularly to Nexos and other publications in Spanish as an essayist and public historian.

8. Mauricio Tenorio Trillo, Latin America: The Allure and Power of an Idea (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2019). For a previous essay along the same lines but with different results, see his Argucias de la historia: siglo XIX, cultura y “América Latina” (Barcelona: Paidós, 1999).

9. Vocabulario de mexicanismos (mauriciotenorio.net).

10. “Achicopalarse,” in ibid., author’s translation.

11. Antonio Alatorre, Estampas (México: El Colegio de México, 2012).