By HALEY SCHROER

On June 8, 1685, Don Diego de García, cacique, or Indigenous leader, from Tlapa (now in modern-day Guerrero), petitioned the viceroy of New Spain to intervene on his behalf. As the “legitimate son of Don Alonso García and Doña María Bárquez de Sandoval, themselves caciques principales from the same province,” García insisted that he held unique privileges. According to the noble, “his parents, grandparents, and ancestors have always possessed the great honors and preeminence bestowed upon caciques, including the ability to wear Spanish clothing and carry a sword, a dagger, and a harquebus.” Yet, despite such access, García complained that “town justices had impeded him” from carrying himself in this manner.

In response, imperial scholars debated the legitimacy of García’s claim. Although “his father and grandfather were caciques and lived reputably,” colonial law forbade the use of weapons among Indigenous populations. Ultimately, authorities acquiesced that “indios principales may be permitted by Your Majesty to acquire a license.” Thus, the viceroy reaffirmed the cacique’s right to carry personal weapons and García won his case.

The case filed by Don Diego was not a unique event. Rather, it represented just one example of the conflicts that arose in colonial Mexico surrounding sumptuary laws—statutes that barred select groups from wearing certain garments or using particular items. Between 1575 and 1693, Indigenous individuals from over 277 different towns submitted 505 petitions against these restrictions. Yet, in spite of the high number and geographic diversity, this phenomenon reflected an overwhelmingly male endeavor. Only two women requested sumptuary exemptions. The remaining 503 requests belonged to Indigenous noble men facing discrimination for sporting European attire and using status items like swords and horses. As a whole, the documents represented a majority privileged, male perspective.

Such a gender imbalance does not reflect the overall distribution for Indigenous litigation in the colonial period. Scholars of colonial Mexico and Peru have demonstrated that females actively participated in the legal sphere.1 Not only did they actively protect their right to inherited assets, they often fought for fair treatment from fathers, brothers, and husbands. The male-dominated nature of sumptuary petitions thus created an anomaly within the Indigenous legal experience. An important question arises from this imbalance: why did sumptuary requests exist as a uniquely male endeavor?

Sumptuary Laws against Indigenous Communities

In order to understand the gendered nature of sumptuary requests, we must first consider the legal precedents. Spanish restrictions against natives developed throughout the sixteenth century. As early as 1501, the Crown warned natives who “carried a sword, dagger, or any other weapon” that they faced confiscation and “may be condemned to more punishments, according to what the court sees fit.”2 In response to a perceived disregard for the law, the monarchy reissued the restriction six more times over the course of the next 70 years.

By the 1560s, imperial authorities feared their hold on the Americas was waning and launched a series of new policies aimed at strengthening Spanish control.3 In 1568 and 1570, the Crown further prohibited indios “from riding a horse and demand[ed] that authorities enforce and execute the law with no hesitation.”4 At the same time, the 1570s witnessed the beginning of the juridical transition of Indigenous populations into miserables, or legal dependents. Spanish administrators increased efforts to appropriate native lands and replace local authorities with outsiders from other towns. Early modern European ideas of political succession centered around masculinity and patrilineal succession. The petitions developed at a time in which native elites experienced threats to their legal rights, territorial ownership, and political influence.

Cultural Origins and Gendered Implications

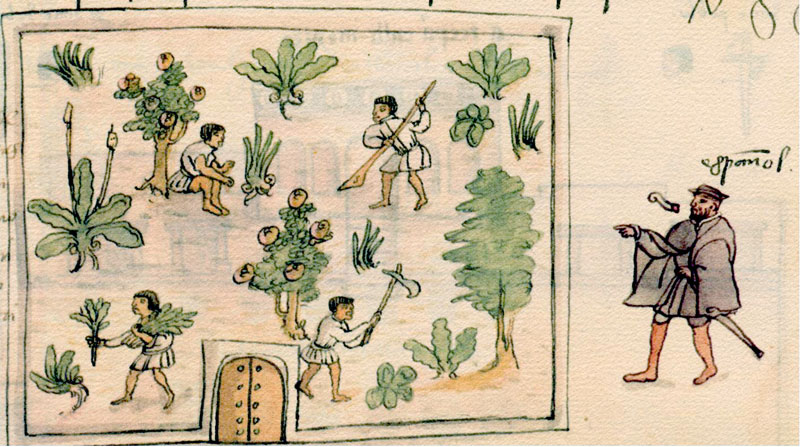

By the time petitions began in 1575, Indigenous men faced increased control over their personal possessions and their participation in colonial society. Yet these laws did not develop in a vacuum. Rather, they built upon pre-existing ideals. At the time of contact, native groups were not strangers to clothing regulations. Pre-Columbian Nahuatl and Mixtec cultures possessed a long-standing tradition of utilizing garments to regulate status and identity.

Within Aztec society, leaders imposed specific laws against their own tribes as well as subordinate groups. Such laws also tended to focus on traditionally masculine items. Rules determined the length and level of decoration on items like capes (tilmatli) depending on one’s standing as an elite, a warrior, or a peasant.5 For example, only nobles gained access to turquoise (both as a color and a stone), sandals, and specific headdresses.6 Similarly, seasoned warriors received capes and jewels decorated specifically for recognition in battle.7 Thus, in everyday life, one’s garments spoke directly for one’s standing and achievements.

At the same time, similar items possessed profound connotations in Spanish society. In particular, military attire played an important role in defining masculine honor. The possession of personal arms assisted in maintaining one’s masculinity. Furthermore, the rise of the espada ropera, or dress sword, by the sixteenth century created new sartorial meanings for the weapon. Meant to complement and enhance men’s clothing, fashionable rapiers became integral to everyday masculine attire.8 Swords, in part, became markers of affluence and upward mobility. For sixteenth-century Indigenous nobility, the combination of native and European elements became critical markers of elite power as they straddled both worlds.

Just as weapons served as status items, so, too, did horses. Steeds possessed deep ties to Spanish society. Within Iberian life, horses acted as a key tool for war and success in military arts. Sixteenth-century scholars applauded the animal as “the most apt for things of honor and the advantage of man.”9 Spanish imperial society valued animals as a means visually to portray dominance in public life.10 Corresponding equestrian accessories, much like clothing, assisted in self-expression in early modern Europe. This gear became critical to the successful portrayal of elite status.11 Not only did a horse provide more efficient transportation, but it also projected images of power upon its rider.

Such colonial values built upon pre-existing Indigenous relationships to material objects. After the conquest, native elites incorporated the shared “social currency” of military garb in both Indigenous and Spanish cultures and focused on items reminiscent of martial service.12 This took the form of European garments, weapons, and equestrian equipment like those requested by Don Diego García.

For native elite men, then, the right to bear arms highlighted much more than their privileged status. It demonstrated colonial acknowledgement of their once dominant standing and partially vindicated their marginalized reality.13 American residents thus conceptualized the sword as intimately representative of its wearer. With the rise of such trends in the colonies, sumptuary restrictions against natives and other non-Spanish ethnic groups situated honorific items like swords within the European sphere. Not only did such possessions provide advantages for transportation and personal protection, but they also connoted inclusion in Spanish culture.

Sumptuary regulations thus emphasized masculine objects like warrior attire, weapons, and horses that possessed profound connotations in both Indigenous and European cultures. The overly masculine nature of laws and subsequent requests correlated directly to early modern gender norms. In Spain, seventeenth-century definitions of manhood similarly privileged visual markers and centered on performative masculinity. Men proved their virility through external markers, such as behavior and appearance. In particular, demonstrating substantial martial skill acted as one of the key tenets to becoming a man.14 By the 1550s, swords became a crucial aspect for elite dress, acting as a sort of male jewelry. In part, this is due to the fact that early modern conceptions of Spanish honor centered around appearance. Building upon the pre-Columbian awards given to successful warriors, Indigenous men incorporated European sartorial values as well. Male apparel possessed greater potential for subversive power because items of attire directly appealed to definitions of masculine honor and reputation in public life.

The items requested by Don Diego García reflected both Indigenous and European definitions of masculinity. By focusing on European attire and personal weapons, García took advantage of the social currency imposed by Spanish colonizers. As an elite, García faced decreased political power and increased marginalization under the new regime. Garments and swords provided the ability to visually assert himself in everyday life. Ultimately, petitions submitted by García and his peers reflected not just a request for special status items but an attempt to assert their belonging as elite men in colonial life. ✹

Haley Schroer is a PhD candidate in the Department of History at The University of Texas at Austin. Her work focuses on the intersection of race and material culture in colonial Latin America.

Notes

1. Susan Kellogg, Law and the Transformation of Aztec Culture (Norman: University of Oklahoma Press, 1995), 32; Jane Mangan, Transatlantic Obligations: Creating the Bonds of Family in Conquest-Era Peru and Spain (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2016); Adrian Masters, “A Thousand Invisible Architects: Vassals, the Petition and Response System, and the Creation of Spanish Imperial Caste Legislation,” Hispanic American Historical Review 98, no. 3 (2018): 392.

2. Recopilación de Indias, Tomo 2, Libro 6, Título Primero, Ley XXXI.

3. Alex Hidalgo, Trail of Footprints: A History of Indigenous Maps from Viceregal Mexico (Austin: The University of Texas Press, 2019), 9.

4. Recopilación de Indias, Ley XXXIII.

5. Patricia Anawalt, Indian Clothing before Cortés: Mesoamerican Costumes from the Codices (Norman: University of Oklahoma Press, 1990), 27, 105.

6. Justyna Olko, Turquoise Diadems and Staffs of the Office: Elite Costume and Insignia of Power in Aztec and Early Colonial Mexico (Warsaw: University of Warsaw, 2005), 225–227.

7. Ibid., 244.

8. Scott K. Taylor, Honor and Violence in Golden Age Spain (New Haven, CT: Yale University Press, 2008); Robert C. Schwaller, “‘For Honor and Defence’: Race and the Right to Bear Arms in Early Colonial Mexico,” Colonial Latin American Review 21, no. 2 (2012): 46, 239–266.

9. Pedro Aguilar, Tractado de La Cavalleria de La Gineta (Seville: Casa Hernando Díaz, 1572), 5, 9.

10. Abel A. Alves, “Individuality and the Understanding of Animals in the Early Modern Spanish Empire,” in Animals and Early Modern Identity, ed. Pia F. Cuneo (Farnham, UK: Ashgate, 2014), 281, 282.

11. Maria Hayward, Rich Apparel: Clothing and the Law in Henry VIII’s England (Farnham, UK: Ashgate, 2009, 179; Peter Edwards, “Horses and Elite Identity in Early Modern England: The Case of Sir Richard Newdigate II of Arbury Hall, Warwickshire (1644–1710),” in Animals and Early Modern Identity, ibid., 131.

12. Monica Dominguez Torres, Military Ethos and Visual Culture in Post-Conquest Mexico (Farnham, UK: Ashgate, 2013), 20–23.

13. Delfina E. López Sarrelangue, La nobleza Indígena de Páztcuaro en la época virreinal (Mexico City: Universidad Nacional Autónoma de México, Instituto de Investigaciones Históricas, 1965), 117.

14. Elizabeth A. Lehfeldt, “Ideal Men: Masculinity and Decline in Seventeenth-Century Spain,” Renaissance Quarterly 61, no. 2 (2008): 464, 470.