BY IRMA ALICIA VELÁSQUEZ NIMATUJ

Transitional justice refers to measures both judicial and non-judicial that are intended to redress large-scale human rights abuses. In this article, I focus on two recent cases of transitional justice in Guatemala. The first is the 2013 trial against General and Former President Efraín Ríos Montt and General Mauricio Rodríguez Sánchez on charges of genocide and crimes against humanity against the Ixil people. The second is the 2016 trial against retired colonel Esteelmer Reyes Girón and former military commissioner Heriberto Asij, who were charged with crimes against humanity for sexual violence against fifteen Q’eqchi’ women from the community of Sepur Zarco, Izabal. Both cases reflect the struggles and obstacles faced by indigenous people of Guatemala, especially indigenous women, when demanding justice and confronting members of the state’s security apparatus.[1]

My aim is to highlight how these demands for justice, and diligent, decades-long efforts in the courts, are complicated by the poverty of most of the indigenous and mestizo communities who are fighting for justice, but also by the fact that the justice system is unequal and foreign to them.[2] Reaching the trial stage requires an intense effort against defense lawyers who are experts in sabotage, and who rely on the passage of time as a deterrent to witnesses. It also requires standing up to a justice system that is racist, sexist, often politicized, and easily corrupted. Furthermore, in recent years this struggle has become more complex since economic and military powers have joined forces to discredit survivor testimonies, especially those of women who were victims of sexual violence.

Context

Guatemala is a small but highly unequal country where over 60 percent of the population lives in conditions of poverty or extreme poverty, the numbers higher for indigenous communities. The country is run by eight families who control just over 250 companies, arable land, banks, and almost the entire economy. This small, historical elite, known as the G8, also controls the state for its own benefit.

Guatemala is an indigenous country, a fact that is often hidden by government officials and census data. It is also a country with acute ideological conflicts stemming from a 36-year armed conflict that lasted from 1960 to 1996 and cost the lives of an estimated 200,000 people. The United Nations Truth Commission Report published in 1999 estimated that 626 massacres took place during the war and that over 90 percent of these were committed by state security forces. Within this conflict, indigenous people and women bore the weight of the violence: an estimated 83 percent of the victims were indigenous. Indeed, the UN report concluded that acts of genocide were committed by the state against the indigenous population. Since the end of the war in 1996, survivors from all around the country have organized to demand justice for themselves and their communities.

Two Cases

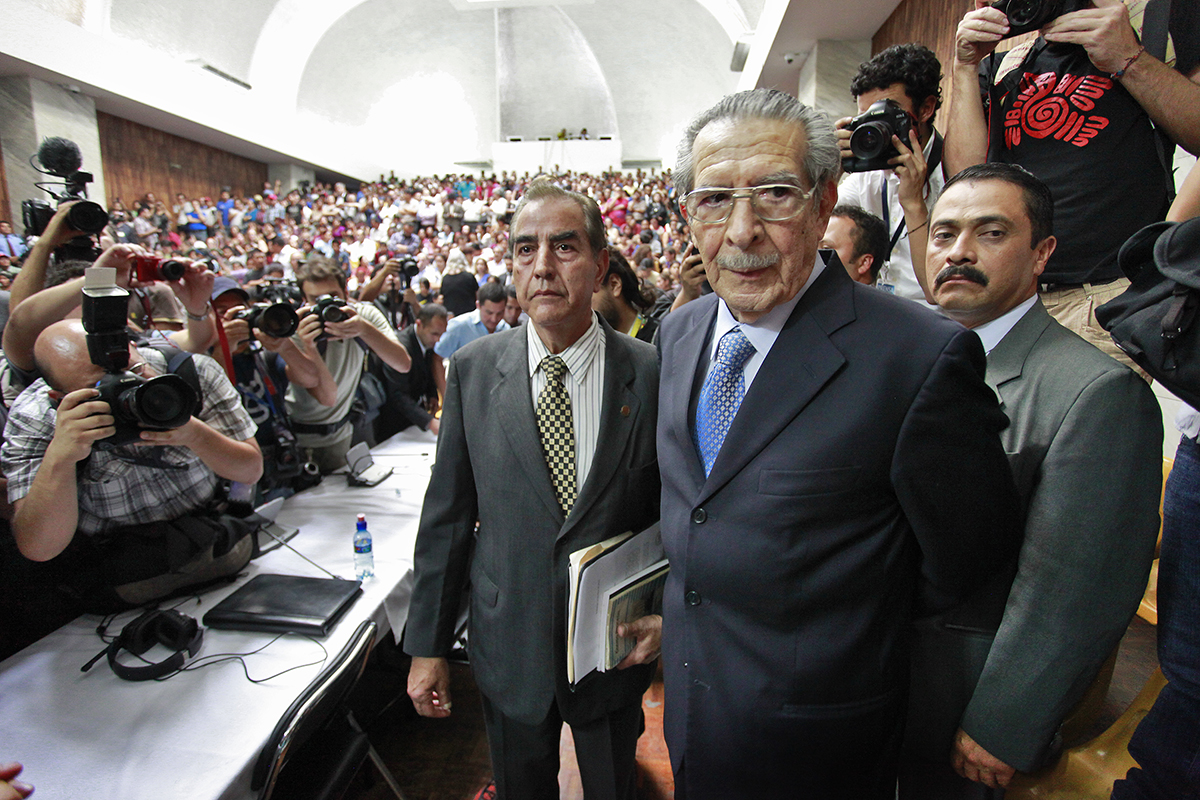

The first case I will discuss is the trial of Ríos Montt and Rodríguez Sánchez, which took place from February to May 2013, more than a decade after the judicial process first began.[3] Both men faced charges of genocide and crimes against humanity for scorched-earth campaigns carried out between 1982 and 1983 against the Ixil people of Santa María Nebaj, San Gaspar Chajul, and San Juan Cotzal. It is estimated that half of the war’s deaths occurred during Ríos Montt’s regime (March 1982–August 1983), which means that in 17 months, an estimated 100,000 people were killed.

One of the most important aspects of the trial was that, for the first time, the voices and the testimony of survivors of the genocide were given national press coverage. Additionally, international coverage made it impossible for the Guatemalan media, which tends to be racist, not avoid publishing fragments of the testimonies, especially those of women, who reported acts of cruelty committed by troops against their families and their worldview, against their bodies and those of their daughters, mothers, and sisters. In one of the most heartbreaking days, one witness, whose identity was protected, revealed that a seven-year-old Ixil girl had died after being gang raped by soldiers and civil patrollers. Until that point, the subject of sexual violence was seldom discussed publicly. Two reports published in 1998 and 1999 made mention of this crime, but due to limited time and obstacles of the postwar era, they were unable to show the extent to which the security forces used sexual violence as part of their counterinsurgency strategy to destroy an imagined “internal enemy,” embodied largely by indigenous communities. In the context of counterinsurgency, the state saw indigenous women as the mothers of future guerrillas and thus a necessary foe.

During the trial, the voices of the survivors were captured in legal documents, pushing back against the official discourse that called them “lying Indians,” and claimed that “Indians exaggerated and twisted reality . . . they could not be raped since they were ugly and dirty.” The women’s testimonies of their suffering also exposed the effects of state-sponsored racism.[4]

The second noteworthy case is a very recent one. In a trial that took place in February 2016, fifteen Q’eqchi’ women from the community of Sepur Zarco, department of Izabal, were called as witnesses against Colonel Esteelmer Reyes Girón and former military commissioner Heriberto Asij, both charged with crimes against humanity. From 1982 to 1988, the military set up a camp in Sepur Zarco on the orders of landowning families who wanted to take control of lands that the indigenous community was trying to legalize as its own. Soon after their arrival, the security forces murdered the husbands of fifteen women, who were then raped and forced into sexual and domestic servitude for six years.

I served as an expert witness for this case, an experience that allowed me to learn and spend time with the women from 2011 to 2013. During those years, and through several trips to Sepur Zarco, I heard their stories and observed their surroundings. It was painful to see the extreme poverty in which they lived because it meant that to this day they are being subjected to a form of state violence. All of the women are poorer now than they were before the military set up camp in their community. One of them has since passed away, at a relatively young age, but this is not surprising given that most of the women suffer from long-term illnesses due to the rape and other abuses to which they were subjected. The Sepur Zarco case set a precedent nationwide with the courts accepting sexual violence against indigenous women as a weapon of war in the Guatemalan context. Internationally, it marked the first time that such a trial took place in the country where the abuses occurred.

During the trial, the fifteen Q’eqchi’ women sat in open court with their faces covered, the stigma of sexual violence still too much to bear. Some agreed to testify in this setting, and with the help of a translator told the judges and the country of the abuses they endured. Others found public testimony too painful, and only their recorded testimonies were presented. Hours and hours of video were played in which, weeping, the women spoke about the horrific way in which the army violated them while destroying their family structure and overall way of life. The violence was such that even the interpreters had a hard time translating these testimonies. In spite of the pain, with their presence and their voice, these women spoke for the thousands of others who have remained silent or who have died without obtaining justice.

These judicial processes are often celebrated due to their implications for transitional justice worldwide, yet the victories do not always translate into concrete changes for the victims and their families. This by no means diminishes the value of the justice or the potential of reparations (as yet unrealized), but it is something to keep in mind. The Ixil and Q’eqchi’ women who testified, most of whom are illiterate, achieved with their courage what indigenous professionals or academics have been unable to do—they reclaimed their dignity. This has implications not only for indigenous peoples of Guatemala but also for the more than 5 million indigenous peoples worldwide, who in different moments of history have faced genocide and other crimes against humanity.

The annulment of the Ríos Montt and Rodríguez Sánchez genocide sentences on May 20, 2013, put a stop to court-ordered reparations. At the time of this writing, a special trial is under way against Ríos Montt. However, these proceedings are taking place behind closed doors, without press access or international observers, preventing accountability and leaving the reparations ordered in 2013 in a legal limbo. In the case of Sepur Zarco, the accused have appealed their sentence and time will tell if court-ordered reparations are instituted.[5]

When we talk about reparations in the Guatemalan context, these often include commitments that should already be the responsibility of the state. In the Sepur Zarco case, for example, some of the measures included the construction of a health center and housing for the women, as well as scholarships for youth in the community to attend middle school and high school. Yet providing access to education and health services should not constitute reparations. These are basic obligations of the Guatemalan state to guarantee the life of its citizens, especially those most affected by poverty who live in remote regions and permanent exclusion.

In the context of counterinsurgency, the state saw indigenous women as the mothers of future guerrillas and thus a necessary foe.

Obstacles

While these cases have provided hope in matters of justice and human rights, the political, military, and economic sectors in Guatemala are to this day campaigning forcefully against these proceedings, using strategies aimed at criminalizing the survivors, family members, and witnesses who are seeking justice.[6] Similarly, as the lack of reparations shows, the Guatemalan state has done very little for the victims of state-sponsored crimes committed during the civil war.

Since 2013, diverse sectors in Guatemala have waged a battle to shape the historical memory of the country. With the start of the genocide trial, sections of the army and the national elite began a campaign to discredit witnesses, survivors, and human rights activists. That same year saw the creation of the Foundation Against Terrorism, an extreme right-wing organization with secret financing, composed of former military. The foundation uses propaganda, paid ads, and media manipulation to defame members of civil society, academics, diplomats, judges, and anyone else, national or foreign, who works on human rights–related topics. Under the banner of freedom of expression, it promotes hate speech in television programs and opinion columns, facing no legal consequences to date. It has even gone so far as to bring charges against human rights activists.

Similarly, the Association of Military Veterans of Guatemala, AVEMILGUA, has focused on creating rural and urban support bases. In rural areas and communities affected by war, the association has tapped into community divisions created by the civil defense patrols to generate support.[7] In Guatemala City, members of AVEMILGUA founded the political party of the current president of Guatemala, Jimmy Morales, and its members now serve as senior advisers and congressmen. During the Sepur Zarco trial, members of the association and their recruits installed themselves outside the courthouse with banners and megaphones, defending the accused while denouncing the Q’eqchi’ women as prostitutes. This argument was even used by the defense lawyer, who in his closing statements claimed that due to their poverty, the fifteen indigenous women had resorted to prostitution in the military barracks. Thus, went the argument, no crime was committed against them.

To this day, the military maintains control over the state and the public sphere. The narrative of the security forces and army as national heroes is undefeated in the popular discourse and has now found its way into academic history books. Additionally, the military has mobilized indigenous populations to protest against the trials and to deny genocide.

The economic elite of Guatemala has joined the efforts of the military associations, fearing that the trials will reveal their direct involvement in the genocide as financers of scorched-earth campaigns. In 2013, it was the country’s chamber of commerce, CACIF, that forced the Constitutional Court to annul the Ríos Montt genocide conviction. During the Sepur Zarco trial, evidence and survivor testimony made it clear that the military detachment had been placed in the region to defend the interests of area landowners against the land claims of Q’eqchi’ peasants.

The actions of the state do not differ from those of the extreme right-wing associations. Through institutions created to focus on the “peace process,” the Guatemalan state has blocked access to files related to the armed conflict, spreading a culture of silence about the past that denies genocide. At the same time, many communities that are still fighting to protect their land and natural resources are being remilitarized.

One official who has pushed to promote impunity and silence is Antonio Arenales Forno, who served as Secretary of Peace during the government of General Otto Pérez Molina (2012–2015), heading an institution created to ensure compliance with the peace agreements. In testimony before the Inter-American Court of Human Rights in Costa Rica and at a meeting on the Convention against Torture in Geneva, Arenales Forno not only denied Guatemalan genocide but attempted to minimize the severity of human rights violations, emphasizing instead the army’s civil security functions. In April 2016, he penned an op-ed in the national newspapers arguing against the ongoing fight for justice. As a general, Pérez Molina was stationed in the Ixil region during the genocide campaigns, yet he has publicly denied that genocide took place in Guatemala. Eyewitness testimony says otherwise.[8] Pérez Molina is currently serving a sentence for corruption.

Conclusion

I would like to highlight three points on the courageous struggle of Ixil and Q’eqchi’ women survivors of the armed conflict in Guatemala. First, we must be careful to not idealize the legal proceedings. These are not just legal precedents, but cases that directly affect the lives of people, many of whom live in conditions of extreme poverty and for whom justice is long overdue. It is important to remember that the struggle does not end when the trial does; survivors still face a society and a state that continue to criminalize them with accusations that they are communists, guerrillas, terrorists, and freeloaders.

Second, the cases mentioned in this article dealt with topics that are taboo in Guatemala. To speak about and denounce sexual violence is not only difficult, but dangerous. Guatemala is still a patriarchal society and indigenous communities are not immune; these crimes affect the internal dynamics in the victimized communities. Fear and shame have forced many indigenous women to remain silent and keep these crimes hidden, even from their own husbands and families. To this day, the majority of indigenous women who were victims of sexual violence have not come forward and many have died. Denouncing these crimes requires work and awareness within indigenous communities, and will necessitate an even more tenacious fight against the patriarchy that plagues the country.

Finally, I stress once again that reparations, while difficult to achieve, are necessary for a country as unequal as Guatemala. Judicial processes are required so that one day, the official narrative will change, and Guatemala will once and for all force its citizens to accept difficult truths: that the state, its security forces, and the economic and cultural elites, guided by racism and economic greed, committed inhumane acts against indigenous people. The struggle of this group of Ixil and Q’eqchi’ women is an inspiring example of hope for the future. That these survivors and their descendants might reclaim their dignity is a small step toward repairing the damage and brutality of the armed conflict.

Irma Alicia Velásquez Nimatuj is a journalist, social anthropologist, and international spokeswoman who has been at the forefront of struggles for respect for indigenous cultures. A LLILAS alumna, she is the first Maya-K’iche’ woman to earn a doctorate in social anthropology. As a Tinker visiting professor during spring 2016, she taught the graduate seminar Gender and Politics of Indigenous Peoples.

Notes

[1] The 1998 report Guatemala: Never Again! prepared by the Human Rights Office of the Archdiocese of Guatemala (Spanish acronym, ODHA) contains detailed information on activities of the army, national police, civil defense patrols, commissioned officers, and death squads during the armed conflict. A 1999 report by the Historical Clarification Commission, “Guatemala: Memory of Silence,” details disparate levels of suffering among indigenous peoples. It lists 626 massacres attributed to state forces as part of a campaign of extermination.

[2] In December 2015, the National Institute of Statistics released the results of the “2014 Survey of Living Conditions” (Spanish acronym, ENCOVI), which shows that poverty and extreme poverty have increased considerably. The national poverty rate reached 59.3%, an increase of 8.1 percentage points over levels found in a 2006 survey, while extreme poverty increased from the 2006 level of 15.3% to 23.4% in 2014. It is estimated that poverty affects 9.6 million people out of a total of 16 million (that is, nearly 60% of the total national population), with 3.7 million living in extreme poverty, most of whom are indigenous.

[3] The film Dictator in the Dock (October 2013) documents the trial of Ríos Montt on charges of genocide and crimes against humanity. See Dictator in the Dock.

[4] Audio available at Peritaje Cultural—Caso Sepur Zarco.

[5] Audio of Sepur Zarco sentence available at Sentencia Sepur Zarco.

[6] Attempts to discredit the victims and their families have included accusations that they are guerrillas, that they are parasites taking advantage of the system, that charges were brought for economic gain and revenge, and that foreign governments have bankrolled their lawyers and stand to gain from convictions.

[7] These paramilitary-style patrols, strengthened during the war years, are composed of rural men forced to monitor their own communities

[8] Otto Pérez Molina has been linked to human rights violations during the time he was stationed at the military base in Nebaj, one of the regions hardest hit by the counterinsurgency, where he was known as Major Tito. It has also long been thought that he was involved in the 1998 plot to murder Bishop Juan Gerardi, a theory documented by the Guatemalan-American writer Francisco Goldman in his book The Art of Political Murder (2007).