by Angela Kang, Alyssa Ashcraft, Simona Gabriela Harry, and Tasnim Islam

Angela Kang:

In late October 2019, a student-led movement sprang up to protest faculty sexual misconduct at The University of Texas. Social media had begun circulating the names of professors who had been found in violation of sexual misconduct and yet were found on the course schedule. The University of Texas administration had made no effort to let students know that we could be in classes with these professors; the onus was on students to inform and keep each other safe. And what students were finding was that the conversation was unfortunately not a new one. In previous semesters, The Daily Texan and student legislative organizations had uncovered a pattern of moving professors who had been found in violation of misconduct policy from graduate supervision to undergraduate classes. This strategy not only denied justice to graduate students who brought forward complaints in the first place, but also endangered undergraduate students, the subjects of an even greater teacher-student power dynamic.

The only public information we could find on faculty sexual misconduct was through stories in The Daily Texan and local news outlets. Student legislation had passed and opinion editorials had been written. Yet, despite semesters of traditional student advocacy, the administration made no commitments to increasing transparency, ensuring safety, and terminating professors who were found in violation of the university’s own policies. Previous attempts to change the status quo ended in closed-door meetings with no changes in policy or practice.

Faculty sexual misconduct is problem that goes well beyond the University of Texas, yet few protections exist for graduate and undergraduate students. At the premier institution of higher education in Texas, students expected and demanded better.

Alyssa Ashcraft:

After several discussions, a group of four students decided to hold a public protest to call attention to this inequity. We created a Facebook event for the “Sit-In for Student Safety” for the following Friday and set to work spreading the word and reaching out to both student and local organizations to garner support. We also drafted a list of student demands that detailed why students felt the need to protest the university’s handling of sexual misconduct as well as outlined changes in university policy that the student body demanded. We presented both the university president, Greg Fenves, and vice-provost, Maurie McInnis, with the document.

The first protest took place on Oct. 25, 2019 in the UT Tower. The event garnered widespread student support. Over a hundred students skipped class, missed shifts at their places of work, and gave up their valuable time in order to show solidarity for their peers and community. Students sat for hours, chanting, crafting signs, and banging their fists on the doors to the vice-provost’s office. As university officials came in and out of the building, students demanded that they be heard and demanded change in the system that had allowed individuals in positions of power to expose their classmates to abuse. That evening, before students left the building, they covered the walls of the tower with their words – of anger, frustration, fear, and passion. While this show of community outrage and support was undeniably powerful, students realized that a single protest was insufficient if our ultimate goal was to achieve structural and institutional change.

Simona Gabriela Harry:

Restlessness. Frustration. Anger.

These were some of the emotions that intruded on my daily life after the first protest. Even though it felt right to confront the university, I couldn’t help but feel unsettled, realizing that the administration hadn’t moved an inch towards justice. Registration came and went; another protest was staged; nothing happened. We received only empty words that blew away a few days later with no action to keep them grounded.

It was a Sunday afternoon. I was sitting at my desk but couldn’t stay focused on the homework I was attempting to finish. That was when I called my best friend, Lynn. One conversation turned into two, and that turned into the creation of a google drive, which birthed a group message, as we expanded. Then, Sit-In 3.0 was in motion, all in one night.

The next two days were a blur. I went to classes. I turned in assignments. I went to meetings. But I had other things on my mind. If we weren’t strategizing how to effectively stage the action, we were researching how to keep consenting protestors safe, or we were crafting phone scripts or contacting the press. School became secondary, an afterthought at most.

Nine in the morning on November 20th, I skipped class to sit outside the Provost’s office and wait. People started to arrive slowly, early even. Professors brought snacks, student organizations brought boxes of coffee, and people came. Yet, the day went fast. Hours felt like minutes as we yelled, made phone calls, and banged on wooden doors and cement walls.

As much as I felt like we had contributed to the momentum that made this issue public, I won’t forget how they laughed at us behind the glass doors or left the phones off the hook, so they didn’t have to hear us. They didn’t really care. We were a show they didn’t feel like paying attention to. I will never regret it. My participation connected me with an amazing support system. I got to protest alongside others who wanted to fight against the powers of administration, and I wouldn’t trade that solidarity for the world.

Tasnim Islam:

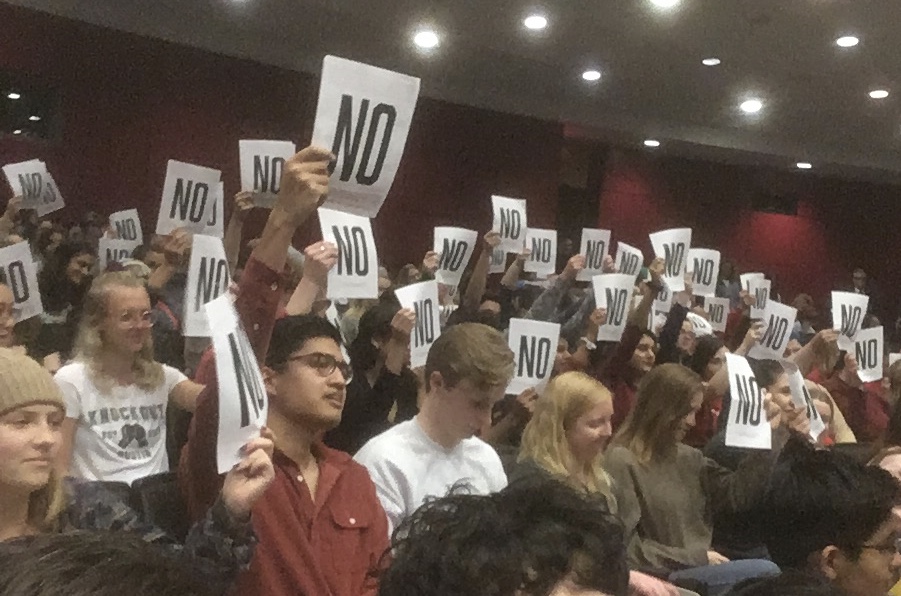

Flash forward to January 26th, 2020. Our fall protests had succeeded in getting university leaders to agree to a public Town Hall Meeting to account for their actions and inactions. In a last-minute attempt to disarm us, the administration began advertising the event as a “student-led forum.” We knew we had to organize if the three administrators slated to appear—President Greg Fenves, Provost Maurie McInnis, and Dean of Students Soncia Reagins-Lilly—were to be stopped from taking the whole event out of our hands. We were invited by the Center for Women’s and Gender Studies to a training hosted at allgo, the statewide queer people of color organization. The training was guided by well-known activists M Adams and Paris Hatcher (M & P). The town hall was high on our student list of demands, so we students had been preparing for the next day ever since October. The training helped solidify some key organizing tactics for the event itself plus our timeline for the rest of the year. All of the “NO” signs held up by audience members at the town hall—a very effective tactic, especially when photographed for the news and social media—were the result of a strategy encouraged by M & P! The town hall was planned by the Misconduct Working Group, which included a few of the students in CASM. We were ready.

However, on the day of the town hall, we were blindsided by the number of police officers on the scene. We had asked for there to be no police at the event because of the racist, sexist nature of policing and law enforcement. We wanted our queer and trans Black, Indigenous, survivors of color to feel safe at this town hall. We were told by the administration that they would not have police there, but shockingly, we were lied to. The rest of the night was an emotional roller coaster for everyone there. People expressed all of their grievances to one another and to Fenves, McInnis, and Reagins-Lilly. Many of us grilled them on the many forms of survivor’s injustice that they had caused or contributed to. There were about 300 members of the UT community in attendance, including students, staff, and professors. We were all fired up with anger and hurt. We were all exhausted. But we got President Greg Fenves to make the admission to survivors that would appear on the front page the next day: “WE FAILED YOU.”

Now it’s Fall 2020 of the era of Covid. After vigorously protesting for our safety for the past eight months, another unnecessary battle is placed in front of us: The Trump Administration’s Education Secretary, Betsey DeVos, has issued Title IX rules to further protect perpetrators of sexual violence, along with eradicating any hope for survivors.

And we’re tired. We’re tired of the gymnastics our physical and mental health have been going through to endure this never-ending fight for survivors. It should not be this difficult to ask for protection from abuse. These new, abhorrent rules do absolutely everything and more to ensure survivors experience as much pain and suffering as possible. Before Devos’s new rules, the original Title IX processes and structures were already difficult to navigate—we’ve witnessed these struggles through decades of community organizing at UT Austin. At the Town Hall, survivors had begged for a crumb of justice from the powerful institution leaders of our university because the Title IX office was atrocious. We have fought tooth and nail over the past few years to finally achieve changed university policies around sexual misconduct. But in spite of these few small wins, DeVos’s new rules feel like a horrific defeat. We’re running out of energy. As college students, we’re all feeling burnt out, especially after advocating for change that affects us all so deeply. Nonetheless, whenever we’re feeling down like this, we constantly have to remind ourselves that while it’s ridiculous that these political obstacles exist, we must use our privilege to continue pushing back against the harmful initiatives of those in authority. We will let it be known that our community won’t stand for our protection to be ripped out of our hands. We will ensure that survivors everywhere receive the justice and healing that they deserve. No one can stop us. No person in power can stop us. No institution can stop us.

Angela Kang is a graduate of The University of Texas (as of spring 2020) and studied Biology and Social Inequality, Health, and Policy. She is passionate about interpersonal violence prevention and committed much of her time to the Interpersonal Violence Peer Support office during her time at UT. She enjoys reading fiction, making lattes, and discovering new music. You can find her on Instagram at @angela_kang.

Alyssa Ashcraft is a senior at the University of Texas studying Government and Humanities with a minor in Arabic and a certificate in public policy. She is passionate about issues relating to educational access and economic equity as they relate to underserved communities. Outside of her professional interests, she spends her time reading, gardening, and travelling. Find her on Instagram @_alyssash.

Simona Gabriela Harry is a senior at The University of Texas at Austin (as of spring 2020) where she studies English and Black Studies with a focus in language, history, and behavioral sciences. She is passionate about education reform at K-12 and higher education institutional levels along with the implementation of thoughtful and inclusive policies that improve educational environments and experiences for marginalized students. She spends her time baking sweets of all kinds, reading poetry, and journaling. You can find her on Instagram @simonathelibra.

Tasnim Islam is a junior at The University of Texas at Austin (as of Spring 2020) where she studies Plan II, Women & Gender Studies, and Portuguese with certificates in LGBTQ+ Studies and Pre-Health Professions. She is passionate about incorporating social justice issues within healthcare curriculum while alleviating healthcare disparities in our system. She spends much of her time trying new recipes and taking hip-hop dance classes. You can find her on Instagram @tasnimislam_.