by Hartlyn Haynes

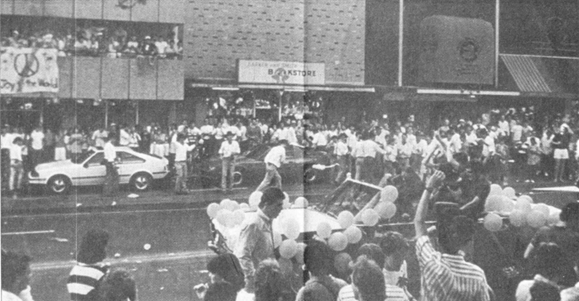

On a Friday afternoon in April 1985, Alex Bernal was attempting to merge into traffic on The Drag when he found himself forcibly blocked out by the other drivers clogging up Guadalupe Street. Bernal was driving the car that served as the Gay and Lesbian Students’ Association’s (GLSA) official float in that year’s Round-Up parade—an event already known for its history of anti-Black racism and minstrelsy—and the other drivers were parade participants attempting to blockade the GLSA float from merging onto the parade route and joining the festivities. When Bernal was finally able to maneuver the float onto the route, students perched on the balconies of the Goodall-Wooten dormitory loudly jeered and pelted GLSA members with rocks, trash, and other debris, hitting one member in the head with a glass bottle. GLSA members sped through the parade route and ended with only minor injuries, but were fearful and intensely angry at the physical attack.

The Round-up assault occurred during a period of intense organizing and action by queer students at UT, particularly those involved in the GLSA and the Subcommittee on Lesbian and Gay Issues (SLGI). The SLGI was an offshoot of the Students’ Association’s Minority Affairs Committee (MAC), which created the SLGI in February 1984 as concern grew about homophobia on campus. A graduate instructor had been fired after asking two queer students to guest lecture about LGBTQ+ rights in her Government course and UT’s radio station had been accused of censoring LGBTQ+-related content. In the minds of student activists, these incidents represented the systemic homophobia at UT. This concern was not new—queer students had been organizing against campus homophobia since the 1940s after multiple professors were ousted over claims that they were “homosexuals” during the rise of McCarthyism.

The SLGI was initially created to investigate “four areas of concern” related to the needs of the campus LGBTQ+ community. These included amending the university’s educational and employment opportunity non-discrimination policy (henceforth, “non-discrimination policy”) to include sexual orientation, investigating grievances concerning on and off-campus housing of queer students, testing KUT-FM’s new policy statement to ensure that LGBTQ+ content would no longer be the subject of censorship, and designing educational programs for resident assistants’ training programs. The first issue was especially pressing for members of the SLGI as it would, if achieved, set a helpful precedent to guide organizing around the other issues.

The SLGI led an extensive campaign to add what they ultimately termed “affectional and sexual orientation” to the university’s non-discrimination policy, spearheaded by its first chairperson, Jay Cherin. Cherin and other activists selected this term quite specifically. As they described to the University Council at one point, the inclusion of “affectional” orientation intended to encapsulate “the part of the spectrum of human rapport which does not overtly involve sexuality.”

Early in their efforts, the SLGI discovered that university administrators placed the burden of proof of on-campus discrimination squarely on their shoulders. To demonstrate a need for the inclusion of “affectional and sexual orientation” in the non-discrimination policy, the SLGI designed a campus-wide survey to assess how community members felt about the LGBTQ+ community and the presence of homophobia on campus. They polled over 1,000 people and found that fifty-one percent of those surveyed agreed that “discrimination against homosexuals does occur on this campus” and nearly fifty-five percent agreed that sexual orientation should be included in the non-discrimination policy. However, the data also indicated mixed feelings about whether or not “same-sex attraction” was immoral and concern among students about having a queer person as a roommate, with sixty-one percent of people responding that they would be unwilling to do so.

As they solicited survey responses throughout 1984, SLGI chairperson Cherin and his eventual successor, Marc Moebius, also undertook a vast letter-writing project to secure the support of deans, regents, and other administrators for their campaign. In mid-1985 and with survey results in hand, the SLGI and GLSA brought their proposed policy amendment to the Student Senate for consideration. If approved there, it would move next to the University Council, then to University President William Cunningham, and finally to the Board of Regents. The updated policy would have UT systemwide implications if the Regents approved the change as major legislation.

Putting the amendment through the Student Senate proved to be another fraught task. When the amendment eventually made it to the floor for a vote in October 1985, a group of student senators who opposed it staged a walkout in protest. This faction was led by senator Scott Scarborough, whose tenure included a checkered history on LGBTQ+ issues. While he condemned the 1985 Round-up attack on the GLSA float, he also voted in 1984 to abolish the SLGI (then known as the “Subcommittee on Homosexual Affairs). Before walking out of the Senate meeting in 1985, Scarborough expressed concerns that the proposed non-discrimination policy “may have been written with the intent of endorsing homosexuality” and distributed unsubstantiated statistics about the average number of sexual partners gay men have in a lifetime and made reference to “unnamed diseases.” Though Scarborough was purposely vague, it was clear he was referring to the ongoing HIV/AIDS epidemic, which experienced one of the deadliest years of the decade in 1985. Despite this attempted interruption of legislative proceedings, the proposed policy amendment passed easily, with twenty-six of the remaining thirty-one senators voting to approve it.

After the Student Senate approved the amendment, it moved next to the University Council (UC), a board made up of student representatives, administrators, and faculty from across campus. As UC members discussed the implications of the amendment in December 1985, some cited similar concerns to Scarborough, worrying that it surpassed a statement of equal opportunity and acted instead as tacit approval of homosexuality from an official university body. To mitigate these concerns, UC members revised the proposed policy amendment before voting. In their revised amendment, they excluded the phrase “affectional and sexual orientation” and the clause that would “ensure equal rights for all individuals.” What remained of the amendment was as follows:

Whereas the University Council of the University of Texas at Austin finds every reason for an individual to be guaranteed all of his or her civil rights regardless of his or her sexual orientation, although by this resolution is does not in any way endorse a particular form of sexual conduct,

Be it resolved that the University Council supports the right of any homosexual member of the University community to equal opportunity in all aspects of campus life, and

Be it resolved that this resolution may not be used to grant any special privileges whatsoever to any particular individual or minority group; it only intends to reaffirm the civil rights of all human beings.

After UC members voted on and passed the revised amendment, they sent it to the desk of President Cunningham for approval, after which it would go to the Board of Regents for a vote. Cunningham, however, took no further action on the amendment. It remained untouched and unsigned until it was passively vetoed in 1986. After that, the amendment effectively died.

Student organizing for the inclusion of sexual orientation in the non-discrimination policy continued through the late 1980s and witnessed an energetic resurgence in 1990. Earlier that year, Toni Luckett became the first Black, lesbian student body president in UT’s history. Her election was a watershed for student organizers—members of the Black Student Alliance and the University Lesbians (UL) had collaborated to spearhead her campaign, and her win demonstrated the immense power marginalized groups could wield if they organized in a coalitional political model. Equity-focused campus politics were experiencing an upswing, and student organizers tried to maintain the momentum of Luckett’s win to push for systemic gains for Black and queer students across campus.

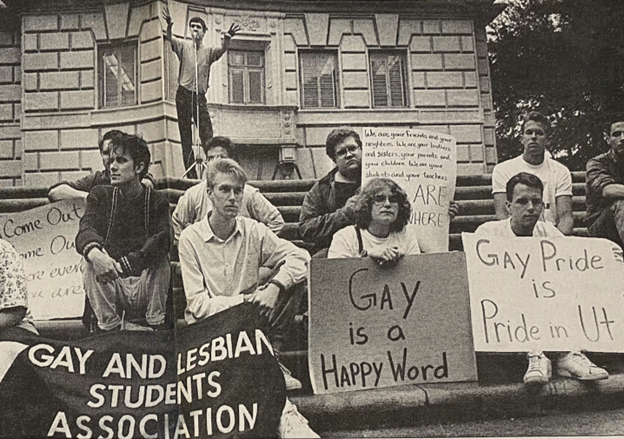

In April 1990, nearly five years to the day since the violent Round-up attack of 1985, 150 students and community members gathered on the West Mall to protest campus homophobia and demand protection from the university, including a non-discrimination clause which was, at that point, “still unwritten.” The April protest inaugurated a new wave of organizing around the issue. In July of that year, a surge of political demonstrations occurred to agitate for an updated policy and protest campus homophobia at large. Shortly after the demonstrations, the UL crafted a petition to demand the inclusion of sexual orientation in the non-discrimination policy.

These events led the university to pass the following non-discrimination policy on August 10, 1990:

It is the Policy of The University of Texas System to strive to maintain an educational and work environment free from impermissible discrimination. In addition to compliance with all applicable federal and State laws and regulations, no person is to be subject to discrimination on the basis of sexual orientation regarding admissions, employment, or access to programs, facilities, or services of the UT System. External users of UT System facilities should also be encouraged to adhere to principles of fair treatment and equal opportunity except as otherwise authorized by laws or governmental regulations.

The policy prevented discrimination on the basis of sexual orientation but did not require any off-campus organizations (“external users”)—many of which operated on-campus due to student membership and the use of campus facilities—to comply with the updated policy. Student activists criticized the change as a “token policy.”

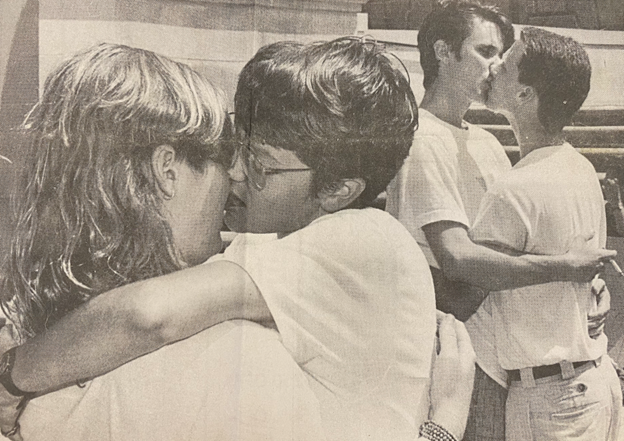

At the beginning of the Fall 1990 term, a coalition of LGBTQ+ student organizations reserved the West Mall for two full weeks of demonstrations aimed at pressuring UT into enacting further, more robust policy reform. The groups’ demands were spelled out in a manifesto authored by the student coalition known as “QUEERS,” which stood for “Queers United Envisioning an Egalitarian Restructuring of Society.” Their demands also included expanded rights for domestic partners and funding for a proposed “Center for Lesbian and Gay Studies.” On the very first day of action, student activists Pam Voekel, Danalynn Recer, Rob Nash, and Derek Roberts staged a “kiss-in” that was documented on the front page of the next day’s Daily Texan.

The photo and accompanying article, penned by Dinica Quesada, created an uproar in the campus community, with Daily Texan editors receiving over 100 responses within a week of its publication, including letters of support and outrage. Quesada, Recer, and Roberts individually received anonymous menacing phone calls and voicemails, some of which included death threats. In early September, someone mailed copies of the Daily Texan issue in question to the parents of Voekel, Roberts, and fellow UL member Liz Henry in an attempt to out them. While the contacted parents were supportive of their children, they nonetheless expressed fear for their safety and concern over the viciousness of campus homophobia.”

As many students pointed out at the time, such actions directly disproved the administration’s common refrain that homophobia was not a concern at UT, despite immense evidence to the contrary. Earlier that year, student activists witnessed Vice President for Academic Affairs Edwin Sharpe approach their protest against homophobia and, at the last second, changed course to avoid interacting with protestors. Members of the UL also described that “after receiving a detailed report on violence against queers at the University, [President] Bill Cunningham told a gay student that he knew of no harassment against gays and lesbians.” These events thoroughly debunked that notion.

The West Mall demonstrations and homophobic fallout exacerbated cracks already present between LGBTQ+ student organizations. One group of students, concerned by the “negativity” and “radicalism” expressed by the QUEERS coalition, formed University Lambda shortly after the demonstrations to provide a politically moderate and “socially oriented” organization for queer students. The in-your-face direct actions created a rift within the GLSA, as well. Recer stepped down from the GLSA board shortly after the demonstrations, critiquing the group for neglecting the demands of women and people of color and challenging members to take a more activist stance. Other students with the QUEERS coalition felt frustrated trying to work within a system that was “racist, sexist, and homophobic,” and turned their attention to other issues in the coming years. Students like Recer, Chapin, and others demanded organizations engage more directly with intersectionality in their politics. These demands were related to larger campus conversations occurring at the time about vast disparities in the racial, class, gender, and sexual demographics among students and a demand for increased structural supports for equity for marginalized groups.

Today, the UT systemwide Handbook of Operating Procedures still includes the sexual orientation non-discrimination policy passed in August of 1990. While the university prohibits discrimination based on “race, color, religion, national origin, gender, age, disability, citizenship and veteran status” in accordance with federal and state law, discrimination based on “sexual orientation, gender identity or gender expression” is, of yet, prohibited only by university policy. While the policy is deeply imperfect, it reflects decades of student organizing and is part of a long legacy of LGBTQ+ activism at UT.

While the QUEERS coalition did not attain every demand in their 1990 manifesto, their demand that the the university fund various research and resource supports for queer students was eventually realized. The critical momentum they and many other LGBTQ+ campus organizations spurred in the 1990s helped galvanize the 2004 founding of UT’s Gender and Sexuality Center, which acts as a critical resource and advocate for the campus LGBTQ+ community to this day, and the LGBTQ/Sexualities Research Cluster, out of which grew the LGBTQ Studies Program and this online publication. These histories, along with the other histories featured on QT Deep Dive, demonstrate the immense power of queer political coalition even when facing a culture of homophobia and an inflexible and often conservative administrative system—a political power we must continue to utilize today.

Hartlyn Haynes is a Ph.D. student in the Department of American Studies and a graduate research assistant at the Harry Ransom Center at the University of Texas at Austin. She serves as a research assistant to Dr. Lauren Gutterman studying UT’s LGBTQ+ history as part of the Campus Contextualization and Commemoration Initiative, which aims to create public history and commemorative projects that shed light on marginalized histories across campus. Her academic research focuses on the intersections of political economy and memory politics in HIV/AIDS memorials in the United States.