Behind this accomplishment was a process that Williams had begun to master, that of transforming individual life experience into art. Place, family, hopes, dreams, and desperation converge in this “memory” play in ways that highlighted the universal qualities of individual experience and that changed the American theater. Theater audiences of the 1940s, fed on a steady diet of “realism and prosaic dialogue,” eagerly embraced Williams’s presentation of a “plastic theatre” that employed multi-media elements suggesting an allusion of reality. Combined with Williams’s poetic prose, it offered up a novel voice that continues to transport audiences into a private world of the human condition.

After his disastrous experience with the 1940 Boston production of Battle of Angels, Williams traveled around the country in near penury for two years before signing a promising but briefly held contract with Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer in Hollywood. As Williams recalled: “From a $17.00 a week job as a movie usher I was suddenly shipped off to Hollywood where MGM paid me $250.00 a week. I saved enough money out of my six months there to keep me while I wrote The Glass Menagerie.”

Just prior to his arrival on the West Coast, his sister Rose was lobotomized. His anxiety and guilt over her fate may have impelled him to concentrate on completing The Glass Menagerie over other plays he was working on at the time.

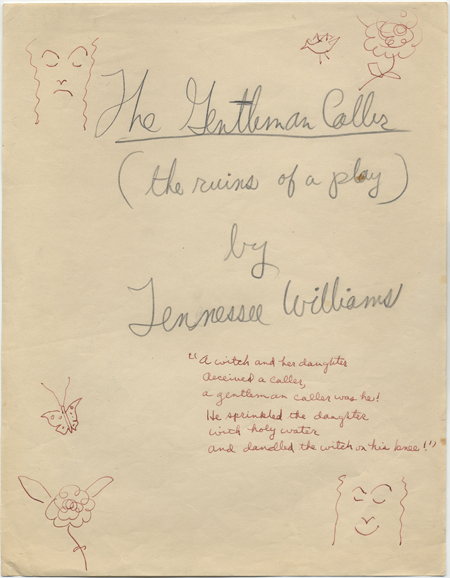

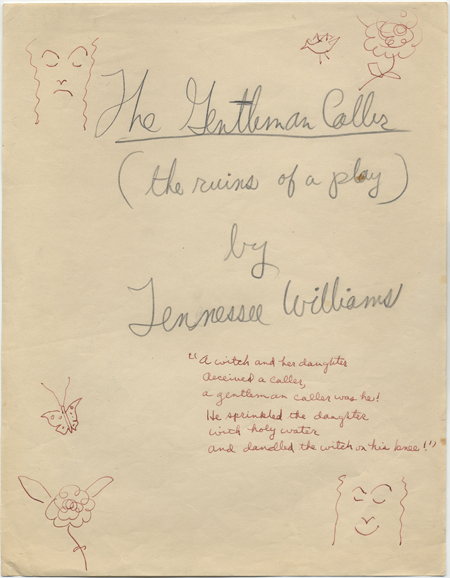

On an early draft of The Glass Menagerie, then titled by a hesitant Williams, due to the negative reception of Battle of Angels, as The Gentleman Caller: Ruins of a Play, are various doodles of flowers and faces. The central point of the title page is a poem of Williams’s:

“A witch and her daughter

received a caller

A gentleman caller was he!

He sprinkled the daughter

with holy water

and dandled the witch on his knee!”

Williams was perhaps daydreaming about the uncertainty of this “play in ruins.” In a letter to the Texas-born director and producer, Margo Jones, Williams, still gun shy from his traumatic experience with Battle of Angels, writes about Eddie Dowling’s enthusiasm for The Glass Menagerie. Williams says he will keep his distance during rehearsals so “they won’t plague me so much about little changes that occur to them. . . You know how frightened I am of everybody! Especially people in the theatre.”

As we all know, the final product of The Glass Menagerie blasted Williams into stardom. He would later write masterpieces such as A Streetcar Named Desire and Cat on Hot Tin Roof. Lyle Leverich writes in Tom, The Unknown Tennessee Williams (1995) that “for the first thirty years of [Williams’s] life, he was living The Glass Menagerie, and it was from that traumatic experience that his masterpiece—this ‘little play,’ as Williams disdainfully called it—evolved.”

This manuscript can be seen in the Ransom Center’s exhibition Becoming Tennessee Williams, which runs through July 31.