Since July 2011, Harry Ransom Center archivist Amy Armstrong has been processing and cataloging the Denis Johnson papers, which are now available for research. Armstrong shares her insight about processing the Johnson materials.

“Guess what collection I just started processing?” I asked my husband in a voice that implied he would be jealous. “Denis Johnson!” Johnson is the author of Jesus’ Son and Tree of Smoke. I have his books in my house and he is one of my husband’s favorite writers. So from the beginning, I felt lucky. But then again, I always do. As an archivist at the Harry Ransom Center, every day I have the honor and privilege of interacting with fascinating material.

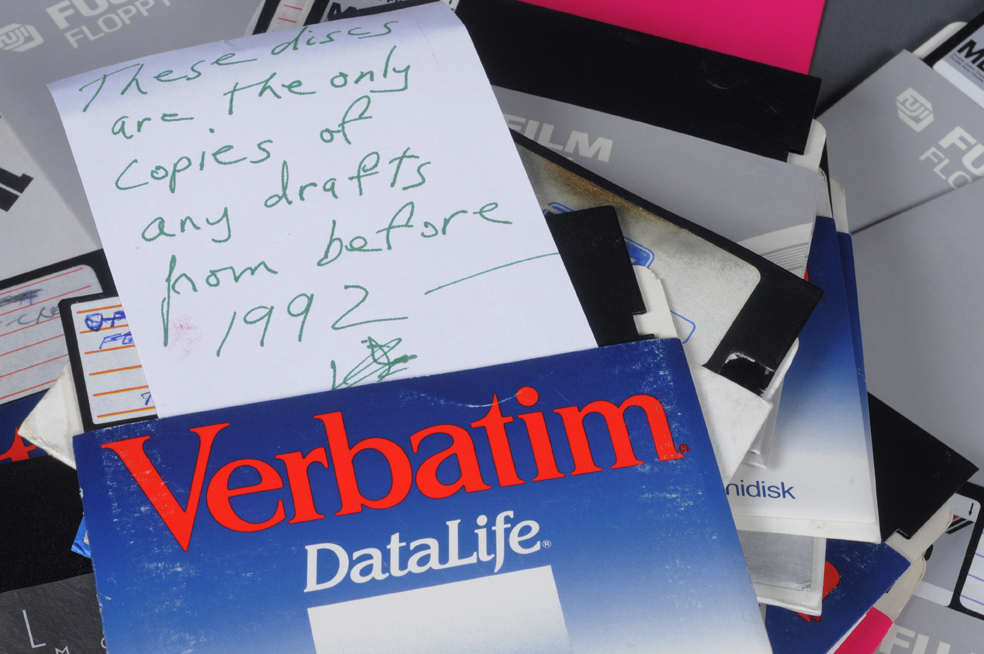

Though primarily composed of writing notes and drafts, Johnson’s papers have a definite intimacy. He created extensive notes and drafts for most of his works, and, at times, he wrote on whatever was at hand, including the back of checks, envelopes, receipts, a set of paper coasters, a paper plate, and a paper towel. One can’t help but picture Johnson sitting at a table somewhere, moved by something he heard or saw, which sparked a thought he just had to get down immediately on whatever he could grab. This may not be what happened at all, but seeing this note written on a paper plate allowed me to connect with Johnson in his everyday life and envision how he lives and works.

Though there is not a lot of professional correspondence in the papers, there are some early personal letters Johnson wrote as a teenager to his parents. These candid letters reveal a young man who already seems to possess the writer’s eye and a gift for observing, assessing, and describing the human condition. In a letter written when he was 17, Johnson, who is working away from home for his uncle in South Carolina, reports on members of his extended family:

Uncle C. S. told me tonight to take engineering in college, and he would give me a job…I told him I wanted to become a writer. He was shocked and completely unable to understand why anyone would want to devote himself to such a worthless occupation. I think if I were one of his own children, he would have beaten me.

Self-assured Johnson goes on to say, “It doesn’t really bother me what C. S. thinks, though, because our values are at such opposite extremes.” Later in the letter, he provides a snapshot of his aunt.

She is so wrapped up in taking care of her home and family that she has little time for anything else. Today in the news there was a story about a Buddhist monk burning himself. She commented that he was not very devout because it says in the Bible that suicide is wrong. I tried to explain to her that Buddhist monks aren’t interested in being good Christians. I don’t think she understood what I was trying to say.

Letters written from college about expected subjects (please send some money, my grades are improving) report Johnson’s struggles in his unmistakable voice and demonstrate his ability to turn a humorous light on some of life’s more trying moments. Johnson updates his parents about his writing in almost all the letters. Here’s an excerpt from one letter:

The stories are coming as fast and furiously as stories can come. Unfortunately my ability to criticize is fast outstripping my ability to write, and I am disappointed in everything. But a good writer is able to quickly fix the blame on a typewriter, the lighting, the weather, the president, and so on.

He also recounts stories of his daily life such as this excerpt about his infant son:

He still does his morning chores, which he picked out for himself and which consist of turning over the wastepaper baskets, emptying the ashtrays (onto the floor), and de-shelving all magazines. He seems to look upon himself as something of a hunter also. Only yesterday he captured my cigarette papers and drowned and mangled them, leaving me smokeless for today.

Though few in number, these early letters reveal a story about Johnson’s early writing and the talented author he was to become.

The Denis Johnson papers are now open for research and consist of professional and personal papers that document Johnson’s diverse writing career and showcase a broad range of creative output that includes poetry, short stories, novels, essays, journalism articles, screenplays, and scripts.

To celebrate the opening of the papers, the Ransom Center will be giving away ten signed copies of Johnson’s Tree of Smoke. Visit the Ransom Center’s Facebook page to see some of the Johnson materials—from a paper plate to coasters—and select your favorite for the chance to win.