Cataloging of the approximately 14,000 titles in the Texas collection of comedias sueltas at the Harry Ransom Center is well underway, funded by a grant received from the Council on Library and Information Resources, Cataloging Hidden Special Collections and Archives program. Appropriately named, this program seeks to support “libraries, archives, and museums that hold millions of items of potentially substantive intellectual value that are unknown and inaccessible to scholars.”

The suelta collection is not a recent acquisition. The first batch arrived in 1925 with a purchase from Professor Clifford M. Montgomery, Professor of Spanish and Portuguese at The University of Texas at Austin. Several other sets of sueltas constituting the bulk of the collection were purchased from various Madrid booksellers, with the last lot acquired in 1939. Thus, for almost 87 years, the sueltas have been awaiting their fate and aging like a good Spanish wine, ready to be opened and enjoyed.

A comedia suelta can be described as a pamphlet-like publication published before the twentieth century containing a single dramatic work. The Texas collection includes works from the second half of the seventeenth century through the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries with a few titles published in the early 1900s.

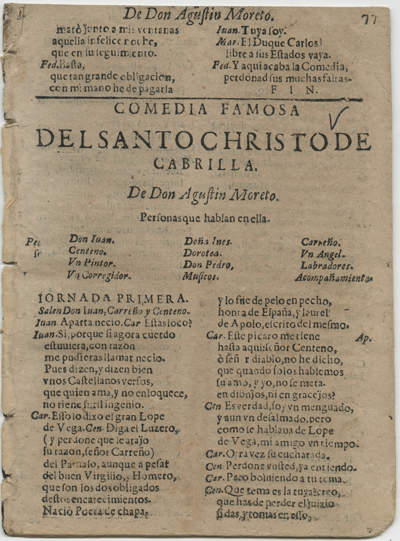

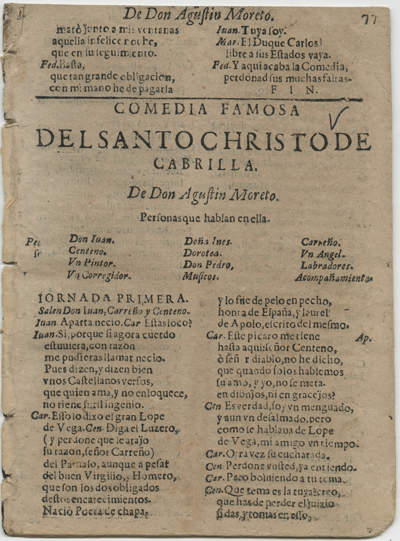

The earliest suelta in this collection dates to 1670. Titled Del Santo Christo de Cabrilla by Agustín Moreto, this work illustrates some of the distinguishing characteristics of the early sueltas. These publications were typically 15 by 20 centimeters in size, with text printed in two columns. While the two-column format accommodated more text, the pages were crowded and left little white space. The orthography and diacritics are irregular and archaic.

After around 1833, the appearance and themes of the sueltas began to evolve with developments in printing and publishing, and societal changes. Printing style and format of sueltas took on a more modern appearance. Language and usage were beginning to normalize after the establishment of the Royal Spanish Academy of Language in 1713, and published dictionaries appeared soon thereafter. The double column format of the sueltas evolved into a single column of text, extending pagination. Title pages with imprints became more common and in the nineteenth century became the norm.

Literary themes of the sueltas also evolved with the material developments. Most of the early sueltas dealt with religious and serious historical subjects written expressly for the Spanish royals. There followed a brief period of romanticism in the early nineteenth century, and then a trend toward satire (of the romantic themes) and what is called alta comedia, a literary realism focusing on social and moral issues.

Acknowledgement and gratitude are owed to Mildred Vincent Boyer, bibliographer and translator and Professor Emeritus at the University, who published her descriptive bibliography of 1,119 sueltas in 1978. Boyer’s Texas Collection of Comedias Sueltas covers the second half of the seventeenth century until 1833. Boyer’s work has been vital in establishing the suelta database currently being created at the Ransom Center. Her hope was that the “10,000 dramatic serials at Texas published after 1833 will have their identity and their whereabouts made known in a much shorter time” than it took her to produce this bibliography.

The sueltas present an array of features that invite further inquiry in addition to the literary content. Upcoming posts will describe some of these facets in further detail: the “cast lists” naming the actors in the repertory, some of them celebrated stars of their day; the “prompt-copies” used for actual performances, with handwritten markings and notations; and “wrappers,” or paper covers, some improvised and others elaborately decorated that provided some protection from handling. The ubiquitous censor and his mark are a common appearance, particularly in the early sueltas. Also of interest are the many inscriptions and effusive dedications from the authors to their benefactors. Indeed, one seemingly ordinary suelta contains a handwritten confession to a murder on its back page. Certainly the cataloging and uncovering of this collection will provide scholars a valuable path to exploring the Spanish national literature and culture of the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries.