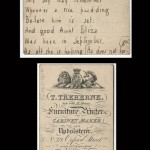

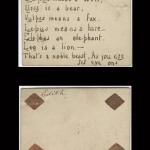

“John Lockland. One thousand one hundred and ninety nine, John his brother to him succeeds: Magna Carta he’s forced to sign: that in truth was the best of his deeds.” This stylized anecdote is but one example of the 399 handwritten verse cards—penned by the English translator, editor, and writer Sara Coleridge—housed at the Harry Ransom Center. The undated cards, written on scrap paper, calling cards, playing cards, advertisements, and invitations, form the foundation of what became Coleridge’s Pretty Lessons in Verse for Good Children; with Some Lessons in Latin, in Easy Rhyme, which was published anonymously in 1834.

The daughter of British poet and author Samuel Taylor Coleridge, Sara Coleridge spent most of her life separated from her father. Despite distance from her father during the poet’s life, Sara became an advocate of her father’s work after his death in 1834. Sara spent much of her adult life editing and protecting the late Samuel Taylor Coleridge’s work, thus, helping to secure his place as a central figure of romantic British poetry.

Yet the legacy Sara ensured for her father’s work often eclipses that of her own work. Indeed, at the crossroads of Victorian womanhood and nineteenth-century intellectualism, Sara Coleridge produced many works that remain largely unpublished.

A child of a prominent English family, Sara Coleridge studied informally alongside her brothers but was excluded from formal schooling. From an early age, she displayed broad intellectual capacity and was a talented linguist. Her education, however, was hindered by the expectations that Victorian women should remain in the domestic domain. Even with her proficiency in several languages, including French, Spanish, Italian, and Latin, Sara Coleridge struggled to overcome nineteenth-century societal constrains.

Despite failing health, by July 1826 Sara Coleridge had published two translations of French and Spanish texts. Acutely aware of the Victorian social pressures imposed on women, Coleridge wrote about the conflated meaning of beauty and the limited role of women in British society. Because of her opium abuse and her extended and clandestine engagement to her first cousin Henry Nelson, anxiety plagued Sara in the late 1820s, and she published little writing.

The verse cards provided an avenue for Sara Coleridge to exercise her intellect. Because the public intellectual character of nineteenth-century Britain was inhospitable to women, Coleridge’s audience was limited to the private sphere. Coleridge delineates her son, Herbert, as the exclusive audience for her verse cards, and she frequently writes his name affectionately in the beginning lines.

The cards reveal not only the breadth and scope of Sara Coleridge’s knowledge but also her style as a writer. Coleridge does not simply list facts to be memorized but presents material about British history, animals, Latin, and geography in stylized verse.

Facing societal obstacles and bouts with poor health and addiction, Sara Coleridge published over ten works, including poems and translations. The verse cards shown here, along with unpublished letters, poems, and manuscripts are available for research at the Ransom Center.

Please click on the thumbnails below to view full-size images.