Andrew J. Walker, Director of the Amon Carter Museum of American Art, presents “Westering America: Frontier Thinking and the Amon Carter Museum of American Art” for the 2013 Amon Carter Lecture on Thursday, December 5 at 7 p.m. at the Harry Ransom Center.

In his talk, Walker will explore the concept of “westering,” which originated from the first director of the Amon Carter Museum of American Art as an innovative approach to the institution’s process of collecting. Borrowed from Frederick Jackson Turner’s famous 1893 declaration that the West had been won, the idea suggests that there was always a “west,” a frontier, from the very early days of America’s establishment. “Settlement,” whether in New England or Cincinnati or the west as it exists today, has been a thread that, 50 years later, reveals a subtle historical point of continuity that has guided the growth of the museum’s collection.

Below, Walker shares his thoughts on “westering,” regionalism, and his museum.

CC: What is “westering?” How is the concept related to the collecting focus of the Amon Carter Museum of American Art?

AW: The concept of “westering” gave a focus to the early collecting patterns of the Amon Carter Museum, when it was actually known as the Amon Carter Museum of Western Art. In those early years, the leadership at the museum attempted to find a way to preserve Amon G. Carter’s interest in the American West—largely in the work of Frederic Remington and Charles Russell—as his principle focus. To carry out his vision, there had to be some acknowledgement of the West as a guiding principle. However, at the same time there was an ambition to be more inclusive of the American experience generally. The solution came about in the notion of “westering.” To the early settlers of our nation, the East was the West and the frontier proved to be a concept that began, for instance, at Plymouth Colony and over time moved progressively across the territory of the United States. In this spirit, the Amon Carter would build on the existing holdings and enlarge its scope to include the whole of the term “western.”

CC: How has the Amon Carter Museum of American Art explored regionalism in the past, and how is the museum’s perspective on the movement unique?

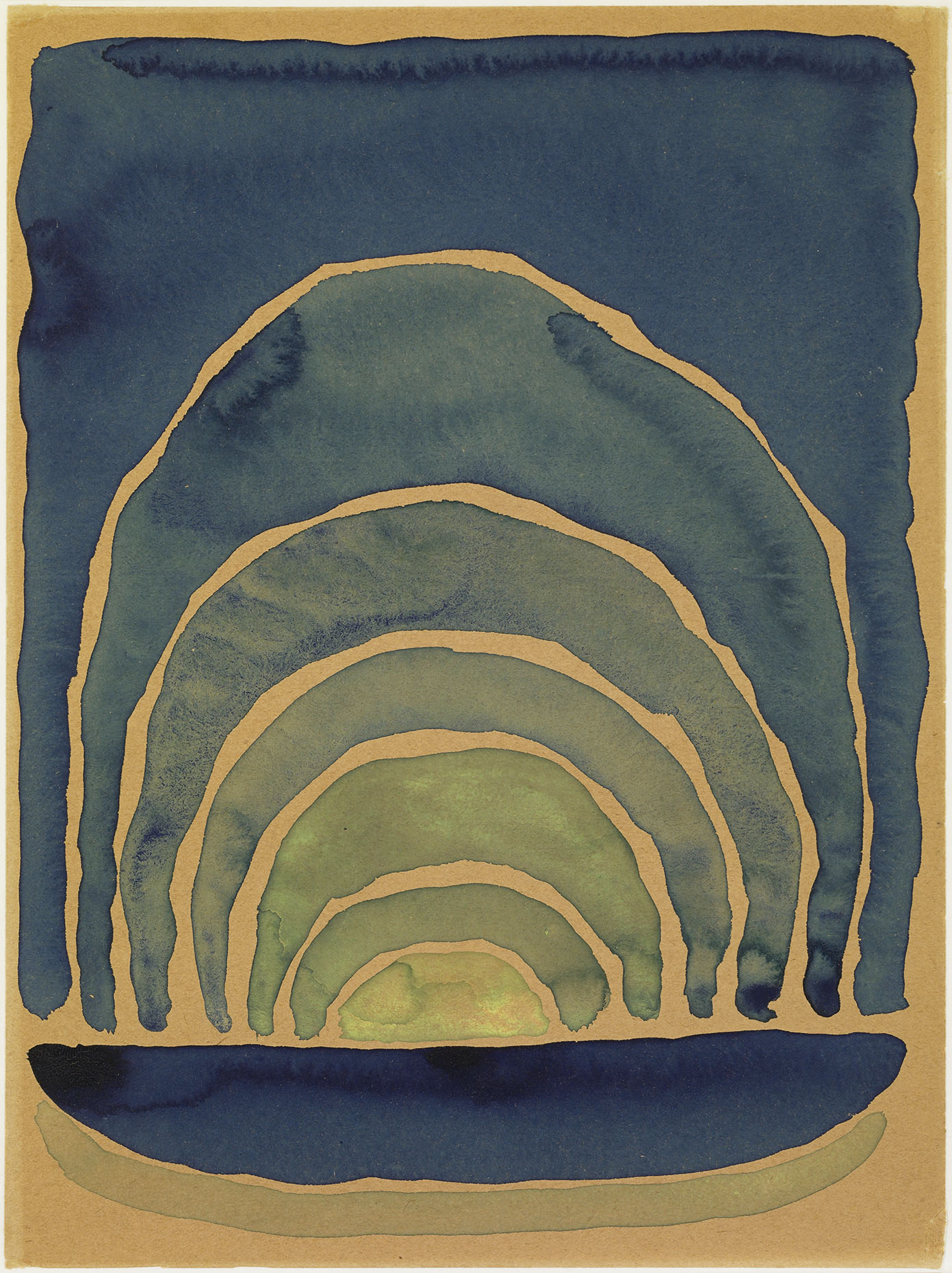

AW: Regionalism as a concept is one that has been episodic but consistent. It has, however, defined its spirit of innovation. As noted in the concept of “westering,” the collection has grown with an understanding of the deep connection people (of diverse backgrounds) have to the land in which they live. But more narrowly, the museum has taken moments to explore that idea more deeply and relevantly to Texas and its impact in the artistic growth of the country. Sometimes it took the form of acquisitions, such as the magical group of watercolors that Georgia O’Keeffe made while teaching in West Texas. They were acquired by the museum in 1966, after being shown for the first time in a major re-examination of the artist’s career that year. My favorite moment, however, came in the late 1970s when the museum commissioned Richard Avedon to explore the identity of the modern American West. The result was the photographer’s transformative series, “In the American West,” which came about through the museum’s particularly assertive stance and is still powerful today.

In the past couple of years, the museum has taken a slightly different approach, recognizing the more specific importance of Texas artists, not only to art history but to the communities of collectors who are drawn to regionalism as a focus. As a continuation of an initiative begun with the 2008 exhibition, Intimate Modernism: Fort Worth Circle Artists in the 1940s, the museum is mounting exhibitions of works in local collections of the best Texas art from the 1880s to the 1950s. Not only is this about great American art, but it is also about relationships of those individuals who find collecting to be rewarding.

CC: How did your personal interest in regionalism begin? How has it expanded?

AW: My interest in regionalism really started through the relationships with various collectors, particularly when I lived and worked in St. Louis, and the inspiration they found in local artists who influenced their collecting. This drew me to names of local artists with whom I was unfamiliar but who had made remarkable achievements in the art world. That ultimately led to a large and important study of the artist Joe Jones, a midwestern social realist who in his day achieved great importance nationally, whose reputation and significant achievement had become lost, forgotten even to his children. The exhibition and book made me realize how significant it is to balance the regional in the national story of American art.

Image: Georgia O’Keeffe (1887–1986). Light Coming on the Plains No. I, 1917. Watercolor on newsprint paper. 11 7/8 x 8 7/8 inches. Amon Carter Museum of American Art, Fort Worth, Texas.