John Mraz is a research professor in the Instituto de Ciencias Sociales y Humanidades “Alfonso Vélez Pliego” of the Benemérita Universidad Autónoma de Puebla. He received a fellowship from the David Douglas Duncan Endowment for Photojournalism and the Andrew W. Mellon Foundation Research Fellowship Endowment to study “Jimmy Hare’s Photographs of the Mexican Revolution.”

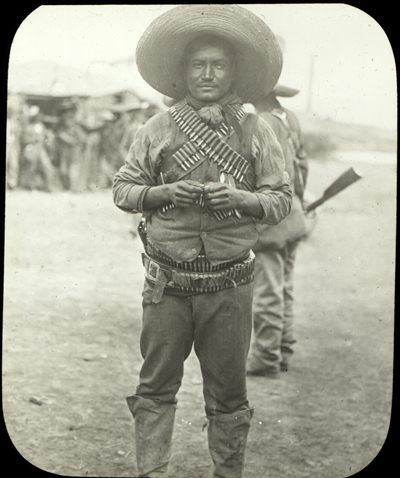

In 2012, my book Photographing the Mexican Revolution: Commitments, Testimonies, Icons was published by the University of Texas Press. The leading combat photographer of that struggle was Jimmy Hare, who brought to Mexico the experience he had acquired in the Cuban-Spanish-American War (1898) and the Russo-Japanese War (1905). The Ransom Center is home to the James H. Hare collection, and, as my book had concentrated on the Mexican photographers (and specifically on determining their commitments to the different factions), I decided to investigate Hare’s photography of the Mexican Revolution in greater depth, with the idea of producing a short monograph on his imagery of that struggle. There are approximately 120 images (largely in the form of lantern slides) in the archive relating to the Mexican Revolution (1911–1917). The great majority of these are of the 1911 battle of Ciudad Juárez, though some ten images of the 1914 U.S. invasion of Veracruz also can be found in this archive.

I had hoped to find new images, especially of the Veracruz invasion, and documents (diaries, field notes, letters, clippings, etc.) written by Hare that could be incorporated into the monograph. It appears, however, this Hare gave that material to his biographer, Cecil Carnes, for the book published in 1940, Jimmy Hare: News Photographer. Furthermore, many Hare photographs that I encountered in the Carnes book and in the illustrated magazine Collier’s are not part of the Ransom Center’s archive. The monograph I had wanted to write will have to wait until the discovery of other parts of Jimmy Hare’s archive.

Although I could not carry out my proposed project, I did find convincing evidence that Jimmy Hare must be considered among the world’s first modern photojournalists. This is an important discovery for scholars of press photography, as we have generally argued that modern photojournalism begins with the Spanish Civil War of 1936–1939 and photographers such as Robert Capa, Gerda Taro, and the Hermanos Mayo. Modern photojournalism is defined by several elements: the photographs are spontaneous rather than posed; they have been taken in the midst of action and with a small camera that permits the photographer to get in that situation without being exposed to enemy fire; the imagery often contains movement within the frame, either because that actually occurred or because the photographer created it by moving the camera slightly or by leaving the diaphragm open longer than necessary; and the photojournalists are committed to one side rather than being neutral observers. Hare alluded to such imagery in his foreword to the Carnes book: “I want to stress the fact here that what I did was to try to obtain pictures of action in the early days of war photography— not just static group scenes.” Obviously, modern photojournalism required gaining access to the front; the censorship practiced by all the armies engaged in World War I prohibited photographers from taking the pictures Hare and others were able to make in the Cuban-Spanish-American War, the Russo-Japanese War, and the Mexican Revolution.

Working in the Ransom Center allowed me to compare Hare’s imagery of struggles where he obtained access to the front to those he made of the Russo-Japanese War and of World War I, which are largely posed scenes of daily life behind the lines. It also permitted me to contrast his photography with that of another early photojournalist whose archive is found in the Ransom Center, Ernest William Smith, who took pictures of the Boer War in 1899. Smith’s images are almost entirely posed—British troops and Boer rebels stand in front of the camera in groups—or they are taken from a distance, in what might be described as “establishing shots.” I have no idea which camera Smith worked with, but there are no “pictures of action” such as Hare described.

Hare was not the only photojournalist to cover the Cuban-Spanish-American War. John C. Hemment photographed that struggle for Hearst publications, and hundreds of illustrated books were produced to celebrate the U.S. triumph over Spain. Whether Hare can be considered the first modern photojournalist will require work in the archives of individuals such as Hemment. Yet, at this early point in my research, it is clear that Jimmy Hare is certainly among the first modern photojournalists in the world.

Related content: