The atria on the first floor of the Ransom Center are surrounded by windows featuring etched reproductions of images from the collections. The windows offer visitors a hint of the cultural treasures to be discovered inside. From the Outside In is a series that highlights some of these images and their creators.

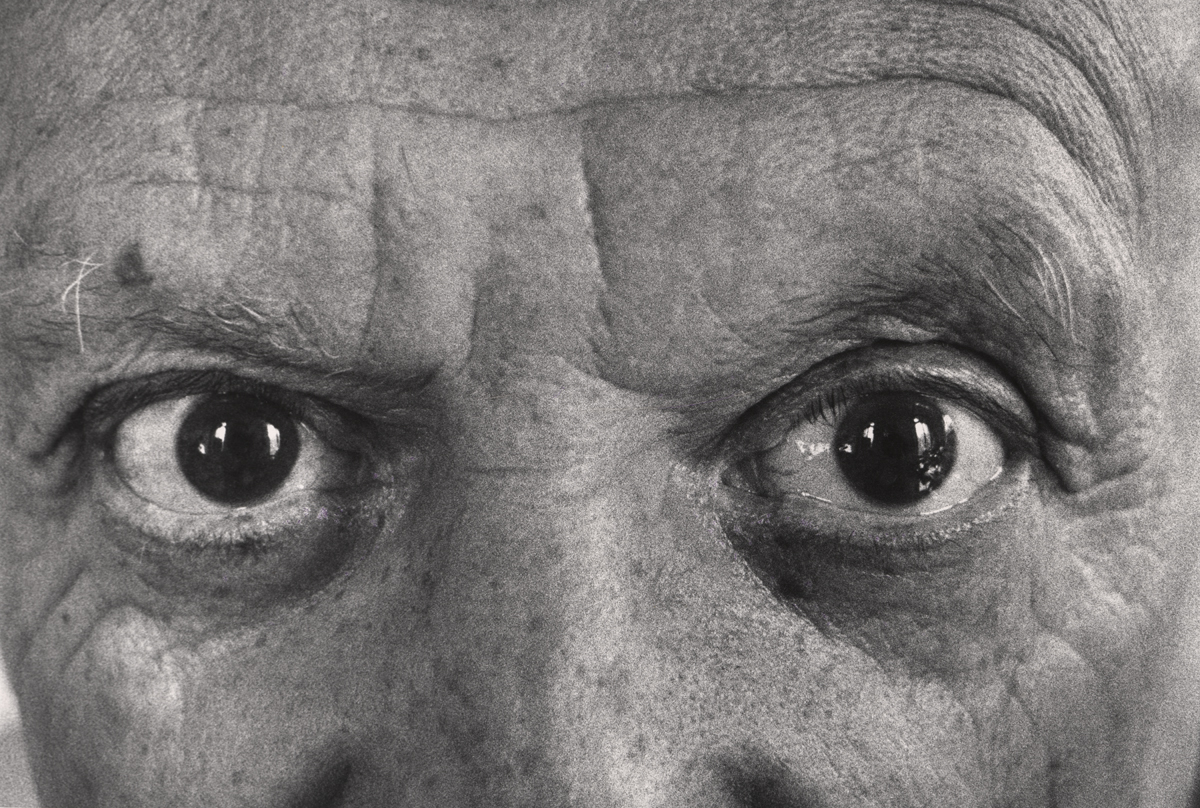

When Pablo Picasso walked into a room of people, his intense gaze commanded attention. He could seduce, caress, or even frighten people with his piercing eyes. His gaze still attracts many Harry Ransom Center patrons, even young school children, when they walk into the south atrium. There they see the window etching of David Douglas Duncan’s photograph of Picasso’s eyes, which calls attention to the Center’s archive of Duncan’s work and to his connection with the artist.

Duncan, an American photojournalist, began his professional career selling his picture stories to newspapers and magazines. In 1943, Duncan enlisted in the U.S. Marine Corps Reserve and was sent to the Pacific Theater. There, he took photographs of aerial missions and operations on the Solomon Islands, the Battle of Okinawa, and the Japanese surrender aboard the USS Missouri. Duncan’s training and experiences during World War II prepared him well for future assignments covering both the Korean and Vietnam Wars. His ability to capture not only the action but also the human face of war, frequently at significant risk to himself, cemented his reputation as one of the greatest war photographers of the twentieth century.

In 1946, just one month after discharge from the military, Duncan was hired by Life magazine to be its correspondent to the Middle East, a position he held until 1956. The magazine sent Duncan all over the world to cover important events, including the end of the British Raj in India, various cultures of Africa, Afghanistan, and Japan, and conflicts in both the Middle East and—most notably—Korea. His photographs and captions reflect the viewpoints of ordinary people as well as those in power. While working for Life, Duncan grew increasingly frustrated when his images were used to illustrate articles by writers with whom he strongly disagreed. So in 1951, he published This Is War!, his own photo-narrative of the Korean War. Since then he has published 25 photography books on a number of subjects.

Duncan has said that his favorite person to photograph was Pablo Picasso. The two met in southern France in 1956, and were friends for the remaining 17 years of Picasso’s life. In 1957, Duncan published The Private World of Pablo Picasso, the first of eight books about the great artist. For the photograph of Picasso’s eyes, Duncan cropped the original image to achieve a dramatic effect. Two copies of the cropped image—which Duncan mounted to canvas—became the foundation for Picasso’s self-portraits as an owl. The Ransom Center holds several original works by Picasso resulting from his close friendship with Duncan; these include a sketch of Duncan at work and a lunch plate painted with a portrait of Duncan’s dachshund, Lump, signed and inscribed to the dog.

Ransom Center volunteer Carol Headrick wrote this post.