This week marks the 70th anniversary of the end of World War II. I grew up in Holland where the fifth of May is celebrated as “Bevrijdingsdag,” named for the liberation from German occupation that my father, who was 14 years old in 1945 when he stood by the side of the road and cheered a stream of Allied tanks and trucks into The Hague, still vividly recalls.

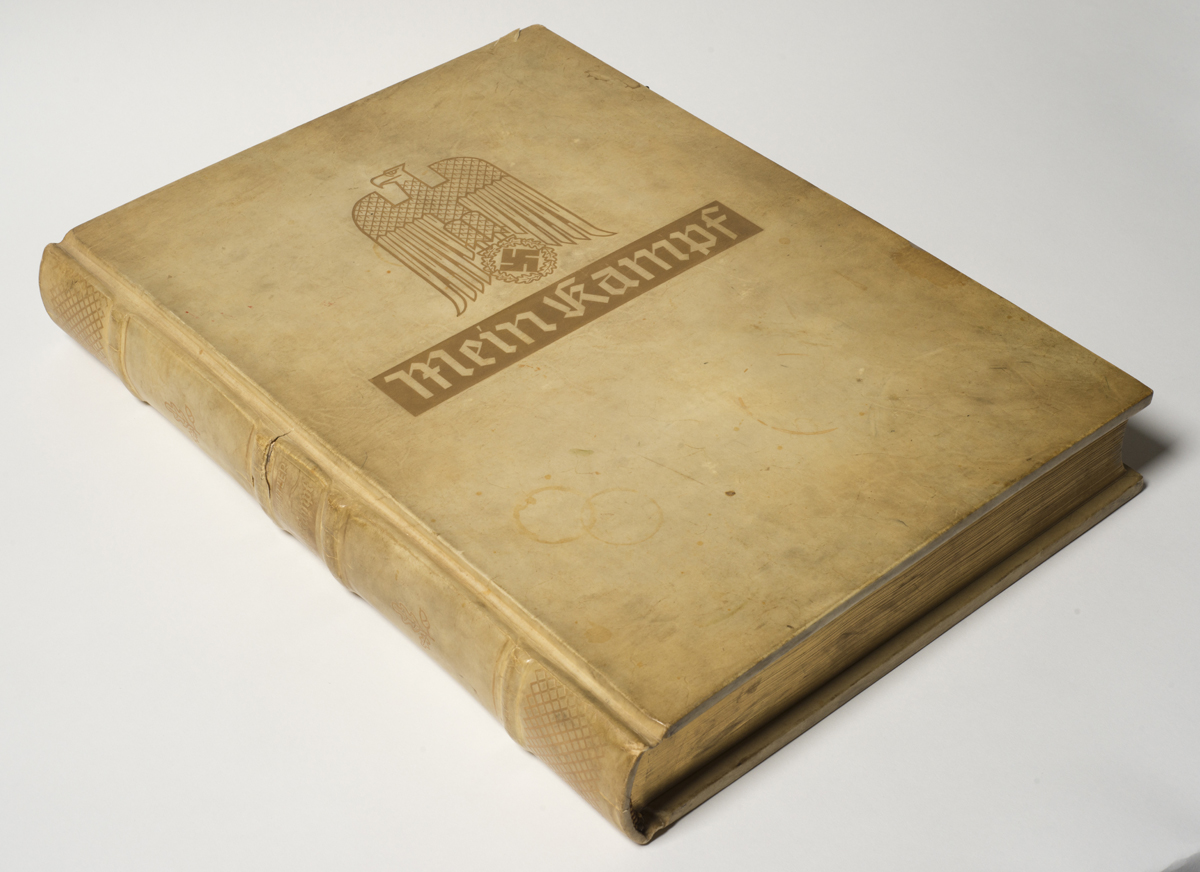

The Ransom Center holds one unique war trophy “liberated” by an American G.I. that weighs in at 23 pounds of evil: a giant vellum-bound copy in heavy boards of Adolf Hitler’s Mein Kampf. Emblazoned on the front with a golden eagle atop a swastika, this large-format edition of Hitler’s manifesto is likely one of fewer than a hundred such lavish presentation copies specially produced in München for Nazi leaders during the war.

The book is now kept in a large box, along with two typed letters from the Red Cross nurse-turned-army-wife, Carmel White Eitt, who donated it in 1988. She writes of its being “liberated by a lad named Willie, a cook in the headquarters company of the 143 regiment” (she could not recall the spelling of his Polish surname), during the search of Heinrich Himmler’s residence in Tegernsee, Bavaria, by the 36th division after the signing that ended the war. Once Stateside, this G.I. showed up at her doorstep to give her his war trophy as a thank-you. I get chills every time I read her letter; even now the hairs on my arms tingle a bit.

A rare wartime survivor, the book has physical features and injuries that tell tales. The battered copy suffers from a slightly “cocked spine,” which makes it want to open to the pages where in 1945 it was stepped on and bayonetted by members of the 36th. Those pages still bear the imprints left by muddy army boots and the ragged cuts and punctures made by bayonets. There is something visceral about the damage left behind—a muddy snapshot of a violent history more compelling than the braggadocio of Hitler’s lavishly printed pages.

This particular copy of this particular book is a powerful object that brings up important questions about why a library or archive painstakingly preserves even the ugly aspects of history. When I show this book to my students, the cover alone is usually enough to solicit disgust from them. Yet in 1988 the former Red Cross nurse wrapped this copy of Mein Kampf in “swadling clothes” [sic.] to protect it on its journey to the Ransom Center. Using language more suitable for a fragile and treasured infant rather than Hitler’s 23-pound screed, this army wife who had witnessed the horrors of war first-hand wanted to preserve her enemy’s book because, as she says, she held a “very deep and abiding affection for the 36th Division and those men who fought so long and so well.” Himmler’s copy of Hitler’s ideas had, over time, become a testament to something else entirely.

This semester I called it up for my undergraduate class “The Paperback,” which studies a number of collections in the Ransom Center to measure the impact that the new portability and packaging of the inexpensive twentieth-century book had on literary interpretation, distribution, and audience. Hitler’s monument to vanity served as my anti-paperback example. His massive commemorative edition demanded veneration with its high production values by mimicking an old book, complete with a blackletter typeface that harkens back to Gutenberg. During our show-and-tell it sat near a giant folio edition of Foxe’s Book of Martyrs, dated 1596, which still bears remnants of clasps and a metal chain (it was likely locked to a desk) and is bound in leather over thick wooden boards. Both the Brobdingnagian edition of Mein Kampf and the heavy Renaissance tome embody the traditional elitist stance towards knowledge that the modern paperback combats. On the same table lay some of the first-generation Penguin Specials from 1938 and 1939, with their no-frills orange and black paper covers: Germany Puts the Clock Back by Edgar Mowrer and What Hitler Wants by E. O. Lorimer. These lightweight paperbacks were, some say, an effective instrument in the war of ideas that helped the Allies win WWII.

Not all books worth keeping look pretty or are even good books. Nor are books always studied for the words printed on their pages. In 1988, Eitt mused how “it is very possible that some feet are still walking around Austin that trod over this volume,” since many men in the 36th had been from Texas. Today, more than another quarter century onwards, these men are unlikely to still be with us in person. But this week, in particular, we remember them and their moment in history.

Receive the Harry Ransom Center’s latest news and information with eNews, a monthly email. Subscribe today.

Click on thumbnails to view larger images.