Miller Williams (1930–2015) wrote, edited, or translated more than 30 books and is best remembered for writing poetry in plainspoken language that captured meaning in everyday experiences. The Ransom Center recently acquired his archive, which documents the career and writings of this influential American poet.

In college, Williams took an aptitude test that revealed, as he once noted, that he had “absolutely no aptitude in the handling of words,” so he switched his major from English to Biology and later received a master’s degree in Zoology. Yet his interest in writing and literature never waned.Williams worked a number of odd jobs and taught college-level Biology before securing a position in the English department at Louisiana State University on the recommendation of his friend Flannery O’Connor. This position launched a long and impressive career in academia and publishing. Williams later taught at Loyola University, where he founded the New Orleans Review, and at the University of Arkansas, where he taught for more than three decades and founded and served as director of the University of Arkansas Press.

As a publisher, editor, and critic, Williams was profoundly influential and mentored many rising literary talents. On the recommendation of a friend, Billy Collins sent a manuscript of about 45 poems to Williams early in his career. In an interview in the Paris Review, Collins noted, “I got a quick response; he’d taken a paper clip and put it around 17 of these poems. He said in the letter, ‘You have 17 really good poems here, and the others don’t live up to that standard. If you can write 25 or 30 more poems as good as those 17, I’ll publish your book.’” Months later, the University of Arkansas Press published The Apple That Astonished Paris (1988), Collins’s first book to draw wide critical praise. In a letter found in the archive, Collins writes, “Thinking back to when I first submitted a manuscript to you, I should also thank you for the wisdom of not accepting it until it was much stronger, though I was understandably disappointed at the time. All things come to those who wait including this astonishing little apple.”

Williams offered careful feedback and advice for many writers. He traded poems with friend and fellow poet John Ciardi, and many of their marked-up drafts of each other’s writings can be found in the archive. In one letter, Ciardi writes with gratitude, “Do you know, sir, that you really are a damned good critic?” Williams’s archive is filled with correspondence from Ciardi and other prominent literary figures, including Collins, Charles Bukowski, Robert Lowell, Flannery O’Connor, Richard Yates, and many others.

Williams worked closely with former president Jimmy Carter on Carter’s 1995 book Always a Reckoning and Other Poems. In a June 15, 1991, letter, which Carter sent with a revised draft of his poems, the former president writes: “You will note that I have tried to pay more attention to meter, remove some of the more obvious riming efforts, use clearer words, and take out some of the clichés. You will also notice how obvious are the benefits from your comments.” The archive includes thick files of correspondence and drafts related to the book.

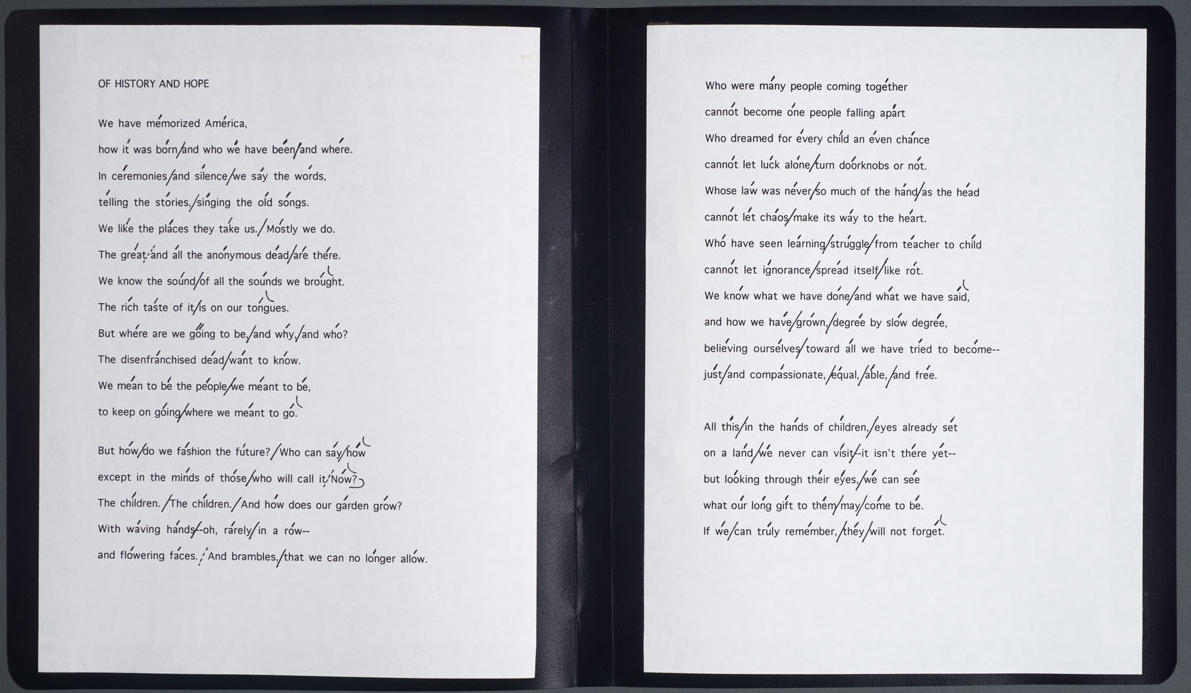

It also includes letters from another former president—Bill Clinton—who enlisted Williams to write and read a poem for his second inauguration in 1997. Williams’s poem, “Of History and Hope,” reflects on both the past and the future of this country. At the bottom of a letter Williams framed from February 20, 1997, President Clinton wrote by hand, “I loved the poem and so did most everyone else—you did Arkansas proud.”

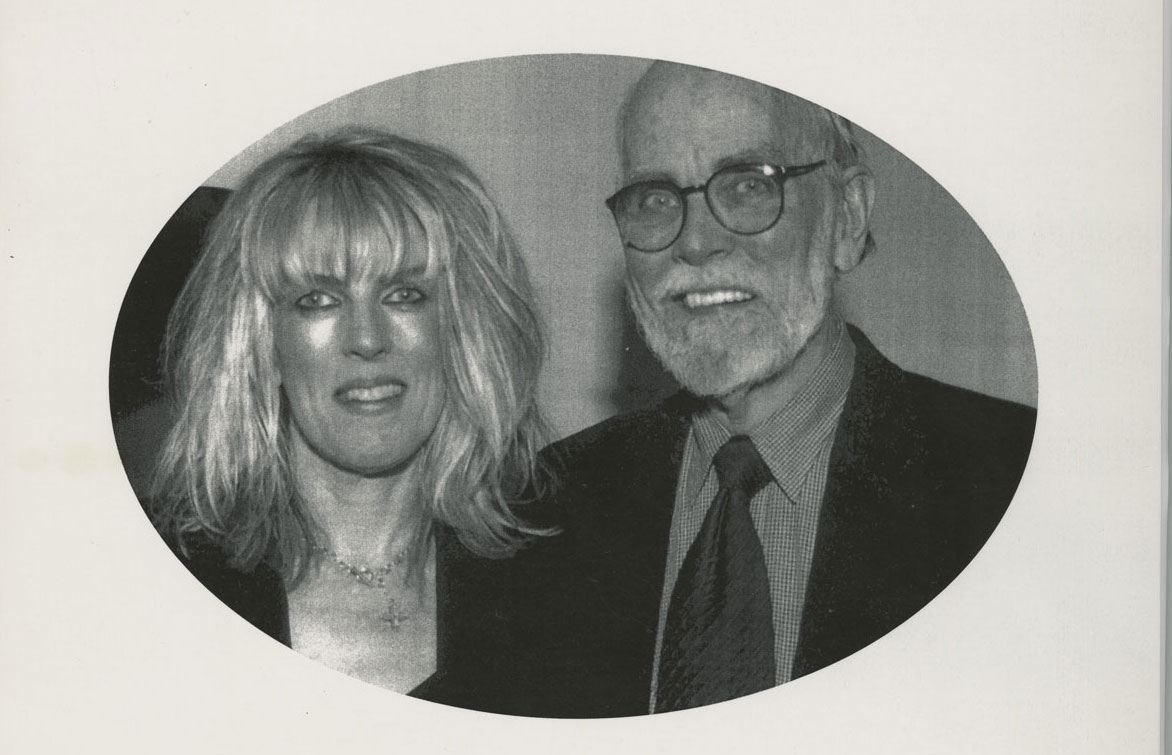

Williams must have had a profound influence on another famous Arkansan, his daughter, singer-songwriter Lucinda Williams. He occasionally shared the stage with her, reading poems between her songs. The title of her most recent album, Down Where the Spirit Meets the Bone (2014), is derived from her father’s poem “Compassion,” which reads:

Have compassion for everyone you meet,

even if they don’t want it. What seems conceit,

bad manners, or cynicism is always a sign

of things no ears have heard, no eyes have seen.

You do not know what wars are going on

down there where the spirit meets the bone.

In his 2006 book Making a Poem: Some Thoughts about Poetry and the People Who Write It, Miller Williams notes that a poem “must have the power to make us respond, to make us more alive.” This sentiment connecting poetry to life resonates throughout his work and his archive—in the many files and drafts of his own writings and in the work he did to publish, translate, share, and bring life to the works of others.