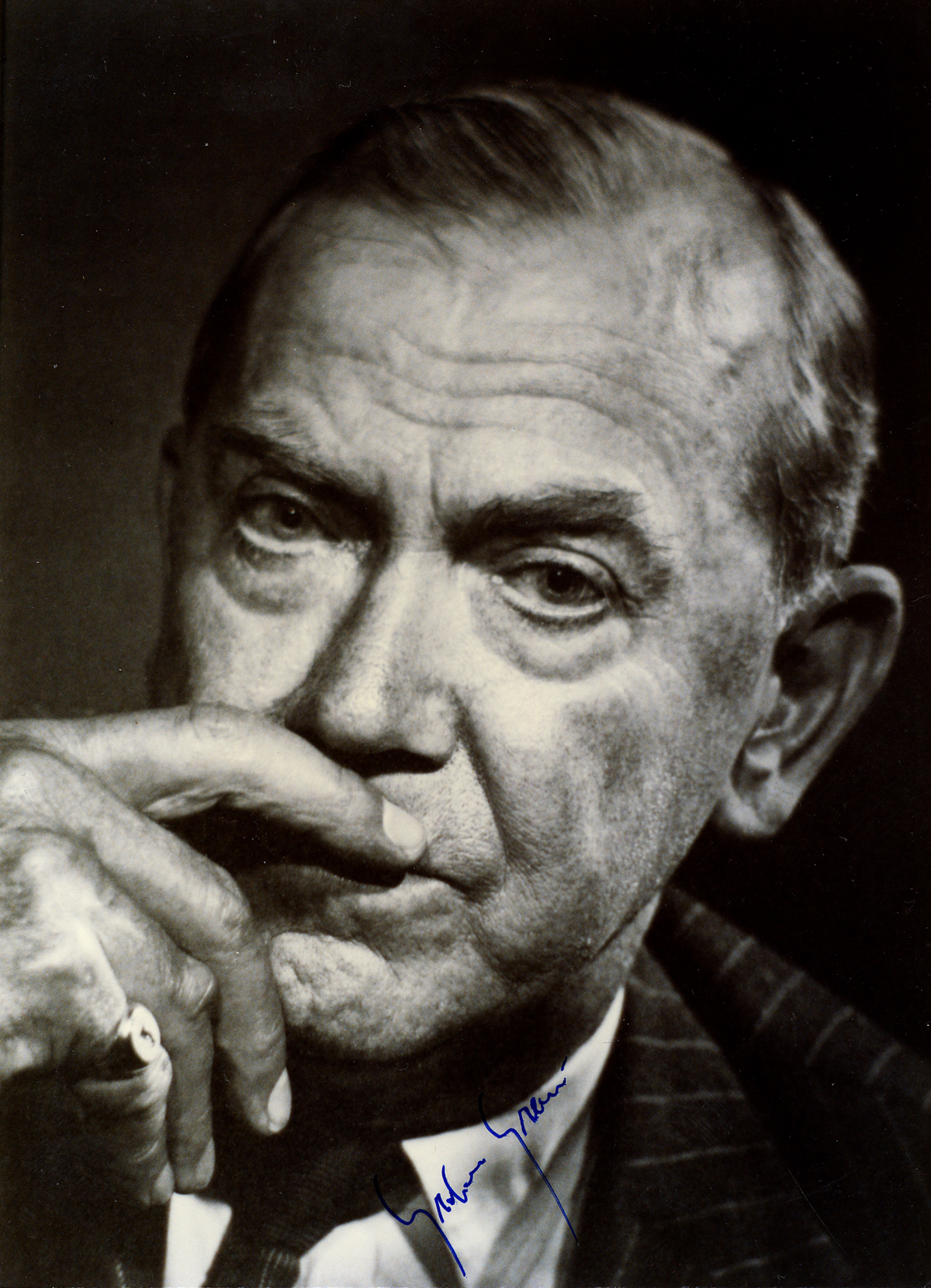

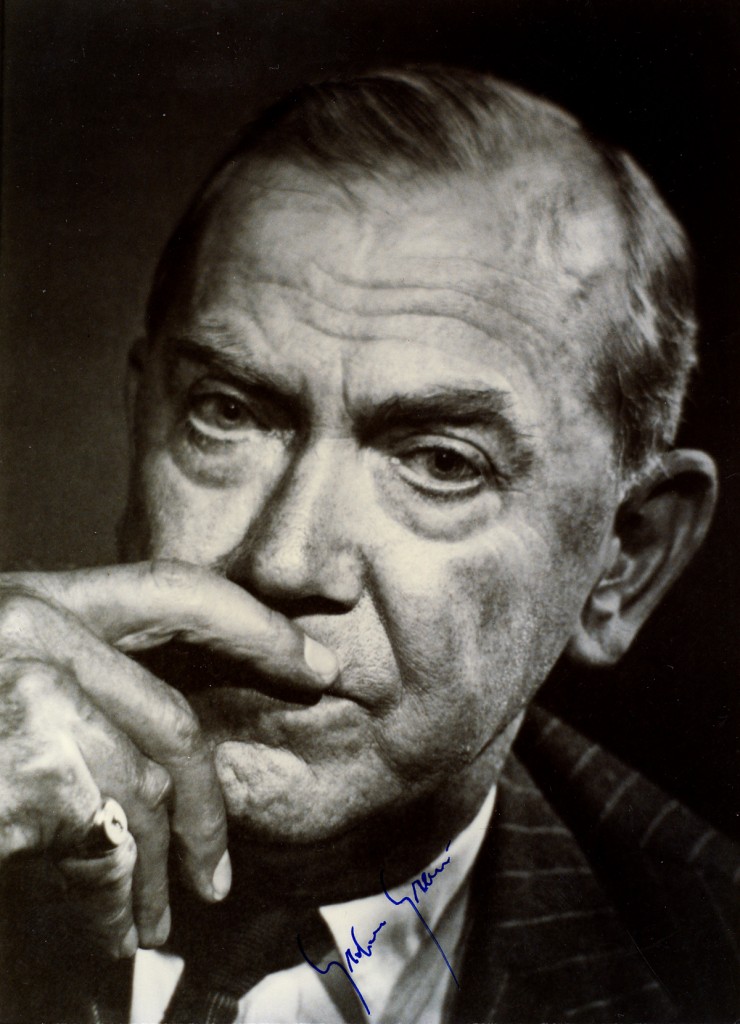

Dr. Jon Wise, an independent researcher and writer, visited the Harry Ransom Center in October 2014 to research the Graham Greene collection with Mike Hill, a retired school teacher and current editor of A Sort of Newsletter, the quarterly journal of the Graham Greene Birthplace Trust. Wise and Hill previously co-authored The Works of Graham Greene: A Reader’s Bibliography and Guide in 2012. Upon the successful reception of that book, the two decided to produce a companion volume that covered Graham Greene’s original writings in manuscript form together with his unpublished work. Their research was supported by the Andrew W. Mellon Foundation Research Fellowship as part of the Ransom Center’s 2014–2015 fellowship program.

During our first visit to the Harry Ransom Center in 2014, Mike Hill and I worked through the existing Graham Greene collection. We were aware that since this collection was last cataloged there had been several important additions that would require a second visit. What we were unaware of, and what made our return visit doubly rewarding, was the existence of three large boxes of extra material, mainly correspondence, which had been acquired by the Center even more recently.

Prior to arrival we had been particularly interested to read Greene’s correspondence with the journalist Bernard Diederich and also with Dr. Michel Lechat. Both men, in different ways, helped Greene to achieve the authenticity for which his writing is renowned and also became personal friends. Diederich had an intimate knowledge of Central America and parts of South America. Greene’s exposé of Papa Doc Duvalier’s dictatorship in Haiti in his novel The Comedians together with Diederich’s investigative journalism helped bring to the attention of the world the true horrors of the regime. Later, Diederich introduced Greene to General Omar Torrijos of Panama. This resulted in the writer visiting the small country on a number of occasions and writing a memoir of the president. There are nearly 140 letters in this collection that date from 1965 to 1990. Although some are copies of correspondence to be found in the Greene collections at Boston College, the Ransom Center’s collection is particularly revealing about their campaign against the Duvalier dictatorship and Greene’s close involvement with Central American politics, which lasted throughout the 1980s.

Michel Lechat first became acquainted with Graham Greene when the writer visited his leprosy settlement in Yonda in 1959, in what was then the Belgian Congo. Greene stayed with the doctor and his family during the time he spent researching the setting for what became his 1961 work A Burnt-Out Case. Greene relied on Lechat’s intimate knowledge as a leprologist to provide details of this little-understood disease that is so much a part of the stark and uncomfortable reality that underpins the novel.

The material in the Ransom Center comes from Lechat’s personal files, and much of Greene’s writing is annotated by him with cover sheets, evidently written in 2007. Half the files consist of materials relating to A Burnt-Out Case and Greene’s Congo Journal and half comprises correspondence between the two men. Prior to publication, the writer sent drafts of the novels to Lechat, and the doctor responded with detailed notes and, in some cases, corrected factual errors in the narrative. He was also deeply critical of some of Greene’s more outspoken comments about individuals who the writer encountered during his stay at Yonda, and these were subsequently deleted from Congo Journal at Lechat’s behest. The 78 letters from Greene are the originals kept by Lechat and date from 1958 to 1988. This is a much fuller collection than at Boston College, which has notable gaps in the sequence of correspondence.

The three uncatalogued boxes referred to above contain some fascinating documents including filmscripts, an abandoned story, a copy of Greene’s U.S. National Security file obtained under the Freedom of Information Act, and a good deal of hitherto unknown correspondence. His letters, among other matters, include his thoughts on encountering the Italian priest Padre Pio, who was thought to bear the Stigmata, and an affectionate and nostalgic sequence of communications with his boyhood friend, the poet Peter Quennell, which includes rare references to Greene’s father. Finally, there is a series of letters some 30 in number, spanning the years 1938 to 1969, from Greene to Ben Huebsch and later Harold Guinzberg of Viking Press, his American publishers. This correspondence provides fresh insights into the writer’s many preoccupations during the middle period of his career. One can also chart Greene’s relationship with Viking Press from his initial enthusiasm over the Viking edition of his novel Brighton Rock to his eventual disillusionment concerning the treatment of his picaresque work Travels with My Aunt.

Hill and Wise’s upcoming book on Graham Greene will be published in September 2015.

Related content:

Read more posts in our Fellows Find series.

Receive the Harry Ransom Center’s latest news and information with eNews, a monthly email. Subscribe today.