One of the delights of processing the papers of an author I enjoy reading is seeing evidence of the work taking shape, unfolding, and ultimately becoming the final story that is published. Revised drafts with lines crossed out and new passages added, early jottings of ideas and character names, original “working titles”…it’s as if I am being let in on a secret. One of the privileges of being an archivist and working with the papers of writers, most recently the Ian McEwan papers, is I know I am one of the rare people in the entire world who is lucky enough to know some of these secrets. In reality, these aren’t actually secrets at all. Ian McEwan, one of the most significant contemporary English writers, selected the Ransom Center to be the repository for his personal and professional papers, and to make them available to researchers. Anyone with a photo ID can create a research account and access almost any of the Ransom Center’s holdings, including the McEwan papers. But for those of you who may not be able to step into the Ransom Center’s beautiful reading and viewing room, let me share a couple of secrets with you.

As I began to open boxes and look at the drafts of McEwan’s novels, I realized that I wanted and needed to read his works (before I worked with the drafts of his writings, if possible). So, I put the drafts aside and began organizing McEwan’s correspondence, so I could begin reading his novels in alphabetical order, as that is the order I would list them in the collection’s finding aid. Once I finished reading a McEwan novel, I would pull out those boxes and begin arranging those materials.

McEwan’s novel, Enduring Love (1997), begins with a terrible balloon accident, and so as not to give anything away, I will quote a passage from the inside flap of the book jacket for the first British edition: “Totally compelling, utterly and terrifyingly convincing, Enduring Love is the story of how an ordinary man can be driven to the brink of murder and madness by another’s delusions.” Throughout the novel, reality and one’s perception of reality is unclear and you wonder who in the book you should trust. Such questions extend to the novel’s Appendix I. It’s a case study, with complete footnotes, reprinted from the British Review of Psychiatry. “A Homo-Erotic Obsession, with Religious Overtones: A Clinical Variant of de Clerambault’s Syndrome” was written by Doctors Robert Wenn and Antonio Camia and describes the behavior of anonymous patient “P” who suffers from the disorder.

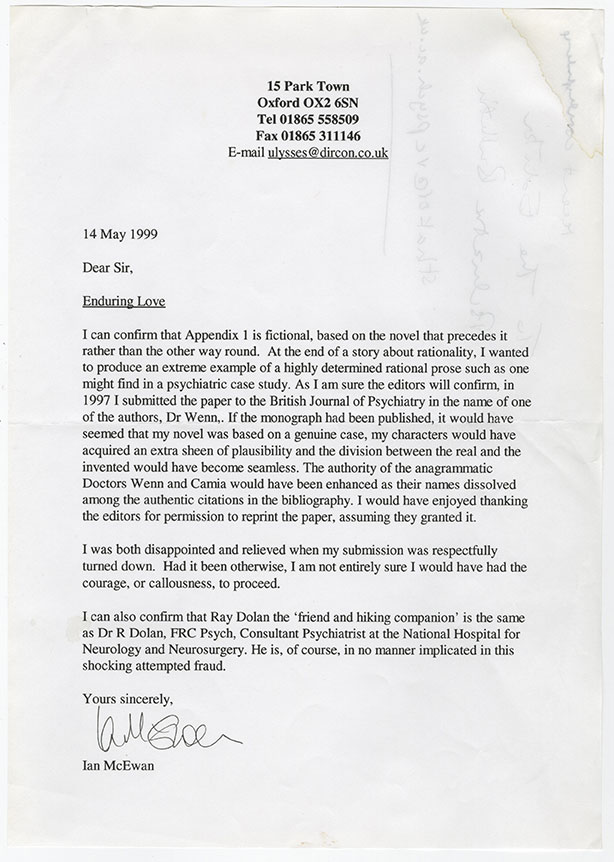

Readers and critics speculated about the authenticity of the appendix and whether the life outlined in the case study inspired the novel or whether the novel inspired the case study. Though McEwan later acknowledged that the appendix was a work of fiction (though the cited references are mostly real), his papers provide some clues.

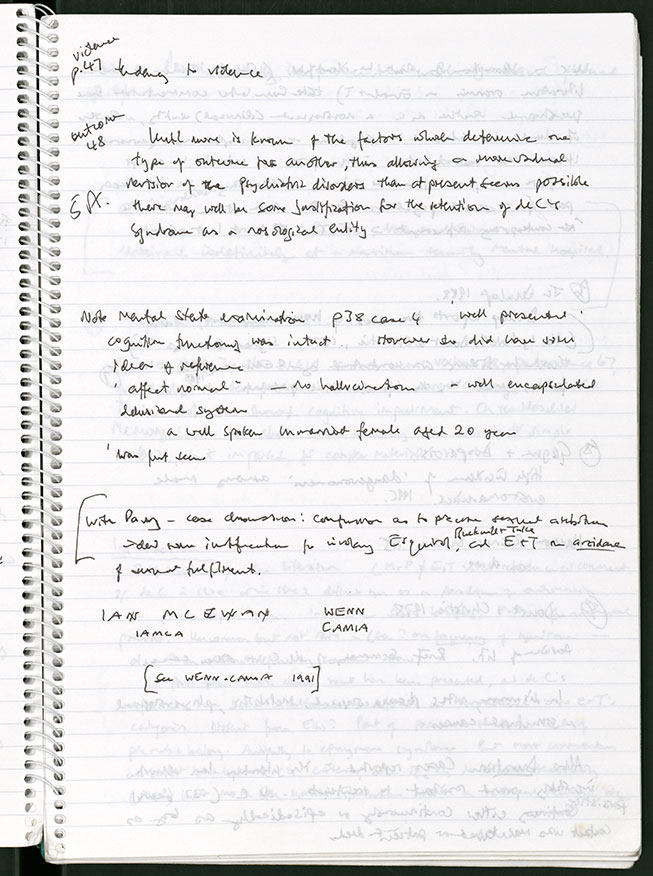

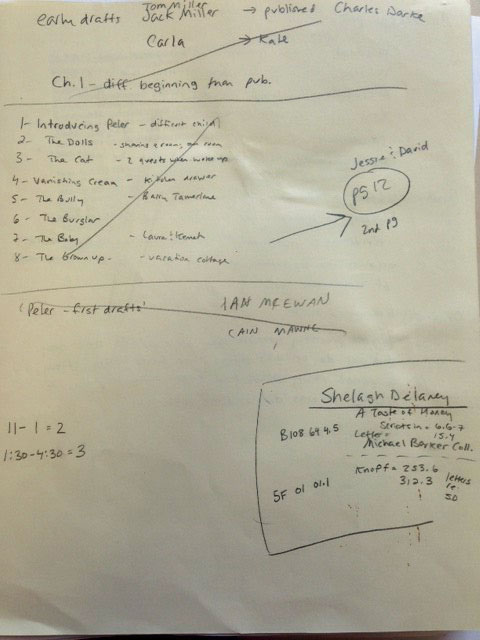

Box 7.10 of the McEwan papers contains the green A4 notebook McEwan used for notes in forming the novel. Near the middle-end of the notebook is the page with McEwan using his name to form the anagram Wenn and Camia; the appendix’s authors.

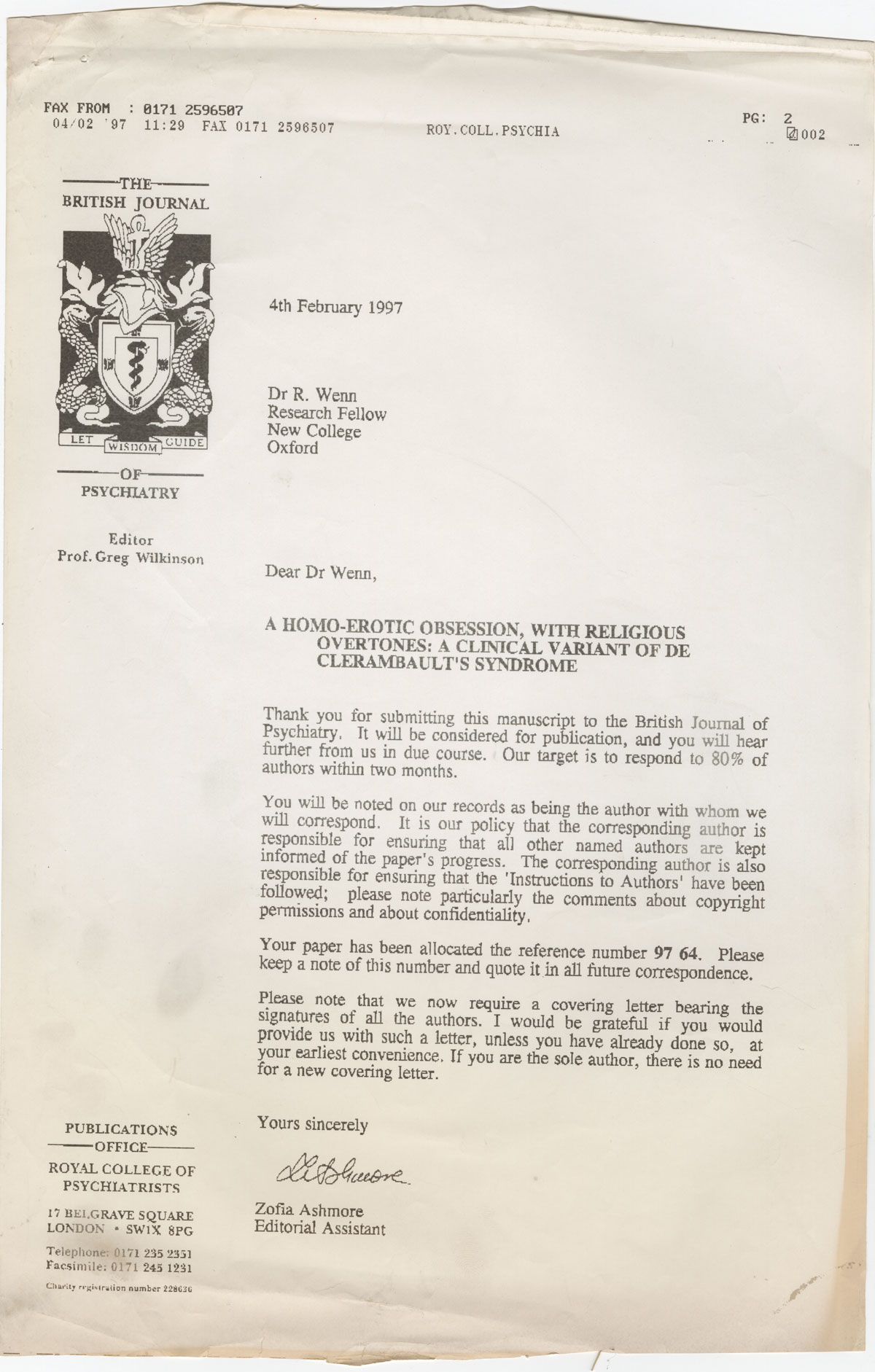

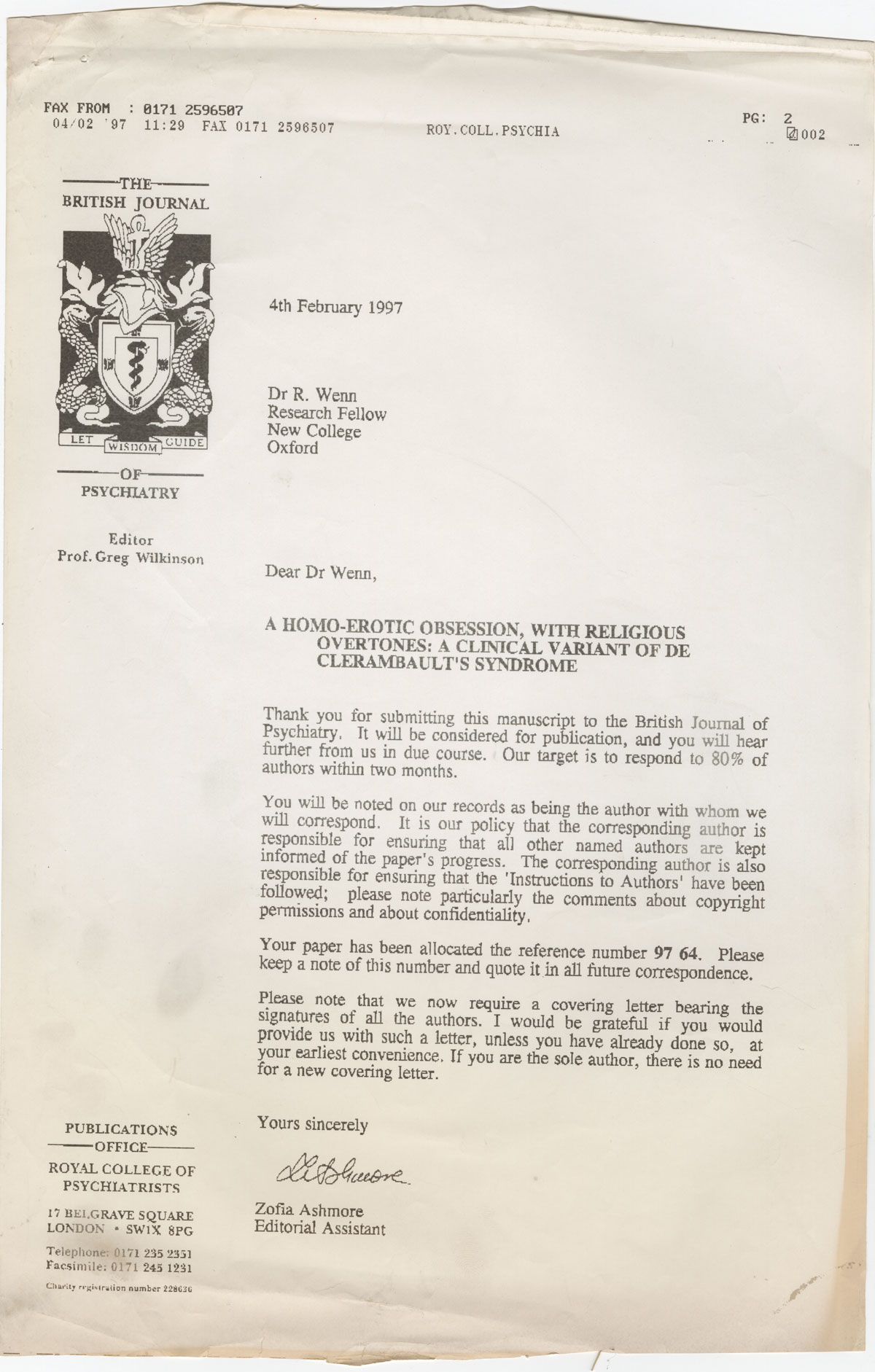

In box 8.1 is a faxed response to research fellow “R. Wenn” from the legitimate publication, the British Journal of Psychiatry, thanking him for his submission to the journal.

As a result of the debate printed in the editorial correspondence of the British Journal of Psychiatry (Psychiatric Bulletin) questioning the appendix and whether it inspired the novel or whether the novel inspired the appendix, McEwan confirms via a letter filed in box 9.5 that Appendix I is indeed a work of fiction. Of course, these aren’t real secrets, but its fun to see the story behind the story.

As I process an author’s papers, I always end up feeling a deep connection with the person. Through their papers, they become a part of my life for about a year, sometimes longer. I am very sensitive to the fact that these letters, drafts, photographs, and other documents represent someone’s real life and not just their career. They allow you to feel as if you are in their moment. I can picture McEwan at his desk and writing out his name and playfully and cleverly coming up with two names for his fictitious doctors: Wenn and Camia. I even did it myself shorty after seeing this in the notebook and came up with two pretty good ones myself: Cain and Mawne.

The Ian McEwan papers are now open for research and many more archive stories await your discovery.