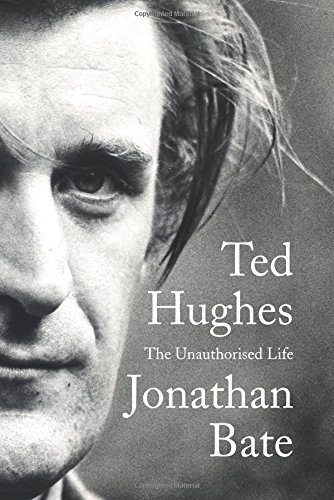

Ted Hughes’s will stipulates that there be no official biography of his life. Scholar Jonathan Bate worked with the Hughes’s estate for four years to create an account of a “literary life.” The result is Ted Hughes: The Unauthorised Life (Harper, October 2015). When the estate suddenly revoked its permission to quote freely from the archives, Bate challenged himself to find a way to continue his project. Bate will discuss his research and rewrite process on Wednesday, November 18, at 7:00 p.m. during the annual Stanley Burnshaw Lecture, followed by a reception and book signing. This program is free and open to the public, but donations are welcome. Seating is first-come, first-served, and doors open at 6:30 p.m.

In anticipation of Bate’s visit to the Ransom Center, we asked him to discuss what he discovered about Hughes in his research.

What drew you to write a biography about Ted Hughes? What about his life and work interests you most?

I do feel that this is the book I was born to write. All my literary passions—Shakespeare, the Romantic poets, the way that literature can address questions of environmental crisis and the relationship between humankind and the natural world, the theatre of ancient Greece and Rome, Sylvia Plath and the relationship between creativity and mental illness—all these came together in the book because they were Ted Hughes’s obsessions.

What were some of your favorite Hughes’ poems before writing your biography? Did learning more about Hughes’s life lead you to favor poems you had formerly overlooked?

My favourites were the poems that had been with me since I began reading poetry as a teenager—essentially those of his first two books, The Hawk in the Rain and Lupercal, written when he and Sylvia were together and happy. “The Jaguar,” “The Thought-Fox,” his memories of the “lost generation” of the First World War, those ones. Spending five years reading the hundred or so books he wrote and the tens of thousands of pages of his manuscript drafts made me admire a far greater range of his work (though I did also encounter a fair number of duds—like William Wordsworth, he just wrote too much!). The two sequences that really went up in my estimation where the elegiac epilogue poems at the end of his strange, disturbing, fascinating long poem “Gaudete,” and “Remains of Elmet” (and especially its revised version, simply called “Elmet”), in which he wrote beautiful poems of memory about his family, his childhood and his native valley in Yorkshire.

Hughes focuses on the natural world in a lot of his poetry. In light of your research, what led him to this focus? How did his nature poetry develop over the course of his life?

This began with his childhood on the Yorkshire moors, and the influence of his older brother Gerald, who was always in the outdoors and for a time became a gamekeeper. It developed with his move to the landscape of Devon in the west of England, and was sustained through his love of rivers and fishing—sometimes in such spectacular places as British Columbia. He also became a more self-conscious environmental campaigner by means of his later poetry and prose.

Ted Hughes was married to Sylvia Plath until she committed suicide in 1963. For many, Hughes’s infidelities during their marriage made him a controversial and unsympathetic figure. In your research, did you discover anything unexpected about Hughes and Plath’s marriage, especially about the time leading up to her suicide?

Yes: the received story gets an awful lot wrong! There was no infidelity in the first six and a bit years. The intensity of the relationship, and Sylvia’s growing mental illness, made things become difficult. Then he strayed, with Assia Wevill. They separated. Sylvia’s work grew in stature when she had space. In the closing weeks of her life, Ted was seeing her almost every day and they were seriously talking about getting back together and giving the marriage another try. But he was also seeing Assia, and another rather fine poet, Sue Alliston. So he was in a mess, not knowing what he wanted. But still helping with the children and sharing Sylvia’s work. The terrible sadness is the volatility that came with her illness: one day suggesting they try again, the next telling him to leave the country and never see her again. Manic depression is the most awful thing.

Access to primary source documents plays a large role in facilitating the research process. How is research material valuable, even when it has severe publishing limitations on it?

It’s absolutely essential. For any literary scholar, the primal experience is immersion in the manuscripts, getting the feel of the pen on the page, the scratchings-out and insertions, the rejected drafts, the breakthroughs, the journal meditations in which writers reflect on their own art. It was such a huge privilege, and the very core of the book, to live with Hughes’s written voice in the archives in Emory and the British Library. My debt, and the eternal debt of Hughes and Plath scholars, is huge: to Steve Enniss, now director of the Harry Ransom Center, who had the vision to buy the first Hughes archive for Emory, and indeed to the Ransom Center itself for inspiring Emory to try to emulate the Ransom Center in the field of British literary manuscripts!

The Ransom Center will be opening an exhibition on William Shakespeare this winter. As a preeminent Shakespeare scholar and biographer of Hughes, what can you tell us about Shakespeare’s influence on Hughes?

I have a whole chapter on that in the book—one of the chapters I most enjoyed writing. Shakespeare was a lifelong obsession for Hughes. His biggest project was the vast book Shakespeare and the Goddess of Complete Being. Amidst a heap of eccentricities, it has jewels of stunning insight into the plays. And, I suggest, it is in some sense Hughes’s veiled literary autobiography. The reason Shakespeare has endured so powerfully for 400 years, which is why there will be all sorts of exhibitions, events and performances in 2016, is that he is the mirror in which each of us sees into our own soul.