Internationally-renowned American photojournalist David Douglas Duncan celebrates his 100th birthday on January 23. For decades, Americans at home and abroad learned of world events as they unfolded before Duncan’s camera, first during his service as a combat photographer with the United States Marine Corps during World War II, and then through his coverage of the Korean War, the Vietnam War, and conflicts in the Middle East for Life. Delivered to millions of households each week through the illustrated press, Duncan’s photographs have played a profound role in informing the public and shaping history.

The Harry Ransom Center is home to the David Douglas Duncan papers and photography collection, with over 100,000 prints, negatives, and transparencies, as well as field notebooks, publications, and manuscript materials documenting Duncan’s life and career. Duncan donated his archive to the Ransom Center in 1996, and continues to add material as his list of publications grows and he experiments with new camera technologies.

A giant in the field, the weight of Duncan’s legacy is clearly felt by the people he photographed and the photographers he influenced, as well as those who have cared for his collection at the Ransom Center. In this four-part series of tributes, we’ve invited contributors to select photographs that hold special significance for them, and to reflect on the meaning of Duncan’s work in their own lives.

Senior Research Curator of Photography Roy Flukinger launches the series this week with a Korean War photograph that has continued to move him since he first encountered it in the 1960s. In the next two weeks, Michael Gilmore, Visual Materials Assistant, discusses a photograph of his father taken by Duncan during the Korean War, and Mary Alice Harper, Head of Visual Materials Cataloging, writes about Duncan’s close relationship with Pablo Picasso. In the final week of the series, photographer Louie Palu discusses the impact of Duncan’s war photographs on his own work over several years in Afghanistan.

All of us at the Harry Ransom Center wish David Douglas Duncan happiness in his 100th year.

—Introduction by Jessica S. McDonald, Nancy Inman and Marlene Nathan Meyerson Curator of Photography

In the nearly two decades that I have had the privilege and good fortune to know David Douglas Duncan, I have considered many of his great photographs to number among my—for want of a better word—“favorites.” Certainly there are a couple of Picassos—the maestro dancing in the studio or the Cubist-like profile portrait of him and Jacqueline—which come to mind. Or the two or three sunflower portraits that will never know an equal. And there are images of Thor, his magnificent German shepherd, which still bring me to tears of both sadness and joy. I could probably go on.

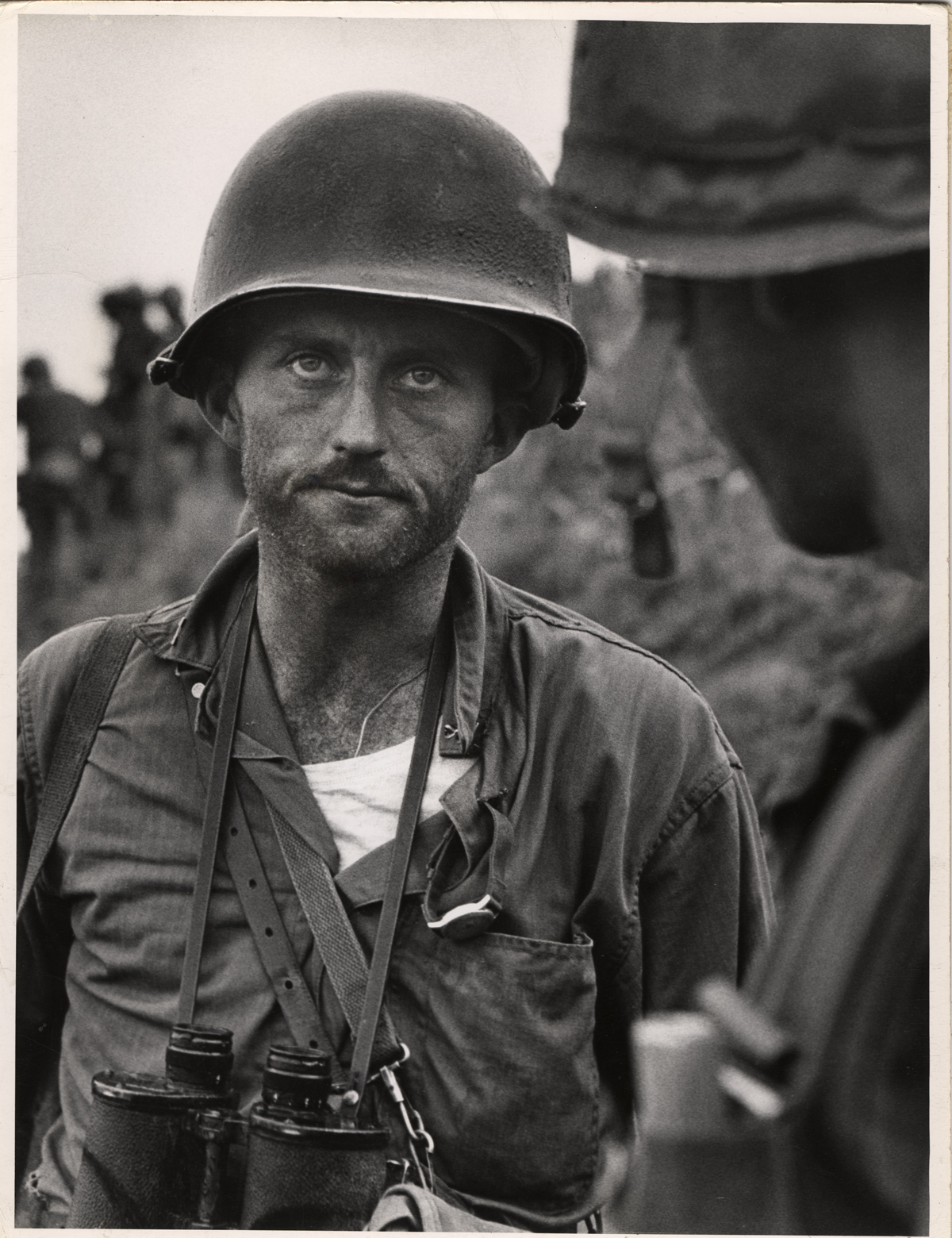

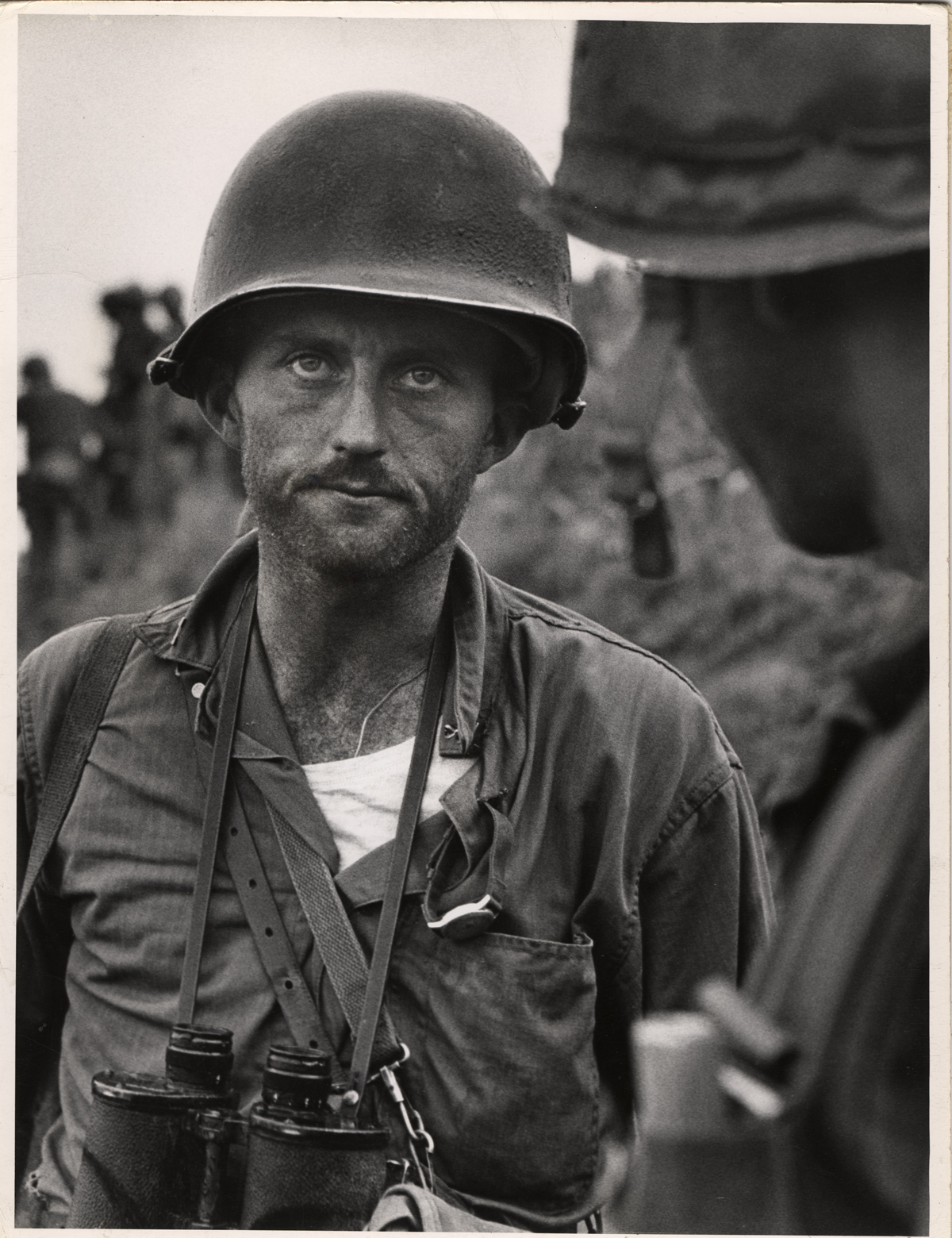

But the war image which has never gone away—indeed since I first saw it back in the 1960s in Duncan’s first book This Is War!—is that of Captain Ike Fenton at the very moment that he was receiving a command report that he could expect no needed supplies or troops in his battle to secure a “no-name” ridge. The portrait of a commander who has received surprising and potentially mortal information with which he must lead his diminishing troops is just riveting. Amid the many memorable Duncan images of the Korean War, this one somehow trumps all others.

Beyond the man’s “thousand-yard stare” as some have called it, I have always been taken by its utter stillness—especially since its framework is the midst of battle. Captain Fenton is a man without a mask, staring at Duncan’s camera without really seeing it. How can you tell your possibly doomed men (and even Duncan for that matter) that this may be the end? What can you read into that face—or perhaps, what can you not? And just what are those out-of-focus figures behind him? His exhausted troops turning to face an unknown enemy, or the ghosts that populate every human battlefield?

While we were preparing Duncan’s major retrospective in 1999, he delivered me the sad news that Fenton had died: yet one more fellow Marine with whom he would be unable to share the exhibition.

One of the titles considered for that show was My Century—a culminating summation of Duncan’s twentieth-century imagery. That title was not selected after some debate, but now I find that Duncan has used it as the title for his very last book (so far) that just came out last year: David Douglas Duncan: My 20th Century. He has made it to the age of 100. It is his century. He has earned it, and he deserves it. And, as he and his archive here at the Center go on into their second century, we shall all continue to be the better for it.

Oh, and the image he chose for the front cover? That of Ike Fenton still staring out over the ages and into the future.