In the final installment of our tribute to David Douglas Duncan in the month of his 100th birthday, photographer Louie Palu offers a poignant reflection on the impact of Duncan’s combat photographs on his own work in war zones. Three photographs from Palu’s series The Fighting Season are featured in the upcoming Harry Ransom Center exhibition Look Inside: New Photography Acquisitions, opening February 9, and more of his work can be studied in our Reading and Viewing Rooms. Once again, all of us at the Ransom Center would like to wish David Douglas Duncan our warmest wishes as he enters his 101st year.

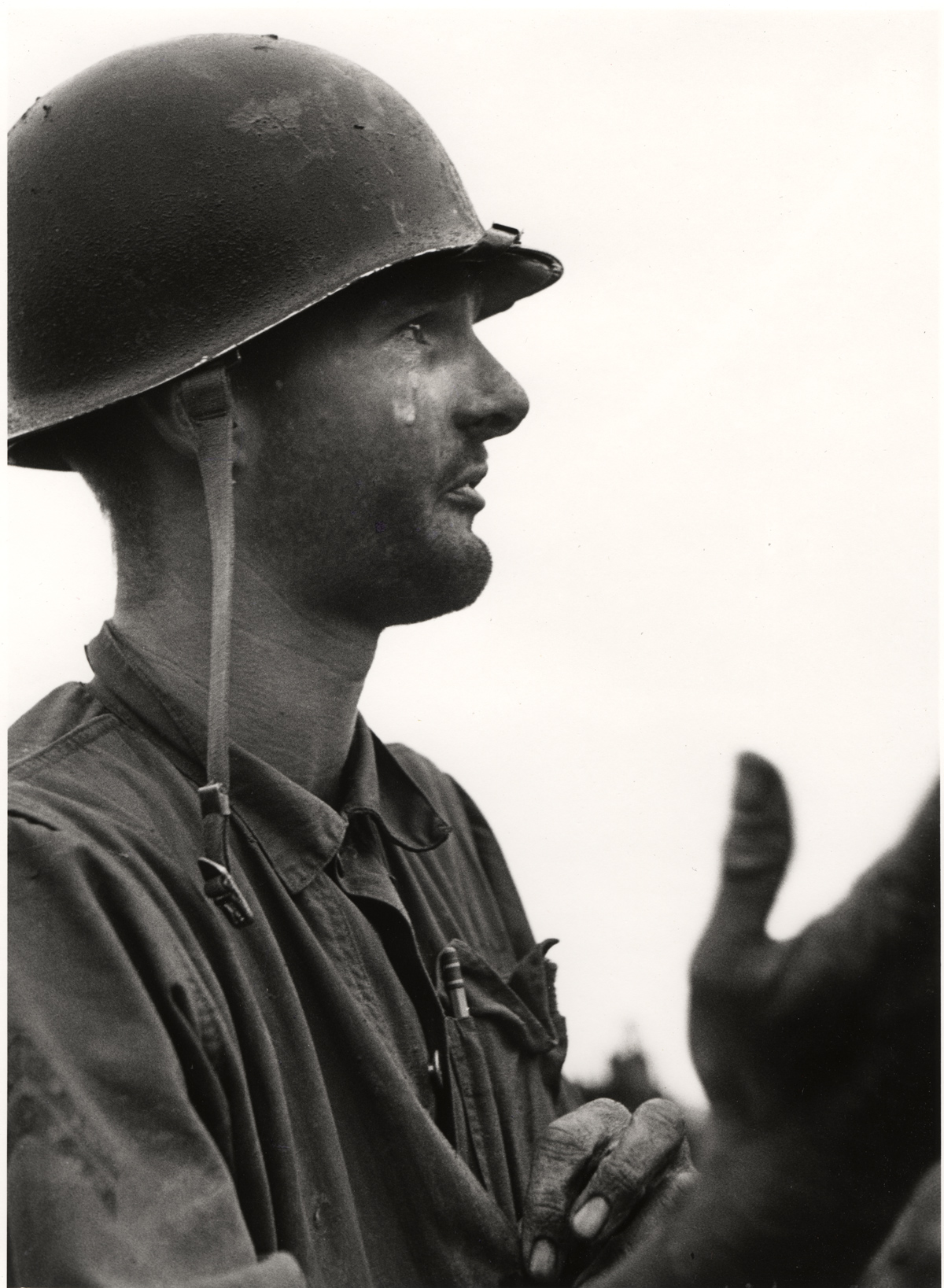

When I was a teenage aspiring photographer I was shaped by the work of David Douglas Duncan. His book of photographs from the Korean conflict, This is War!, expressed the psychological and emotional fragility of human beings affected by war unlike any other photographer’s work. His photograph of Corporal machine-gunner Leonard Hayworth in a unit of doomed Marines under siege on a Korean ridge in the 1950s is, for me, the very pinnacle of war photography: raw, unromantic, painful, and utterly heartbreaking. Through Duncan’s photographs like this one, we all remain connected to critical moments in history as well as to his personal experience living through them.

What I could not have known until I covered combat myself over five years in Afghanistan is what Duncan experienced while taking these pictures. When you arrive at the front line you start out strong, and think you can handle anything. Then every form of exhaustion sets in. Then comes extreme boredom even as you brace for unpredictable chaos. Eventually you witness death. I got to know several soldiers who were later killed, just days or moments after I had been laughing and smoking with them in a trench. I will always wonder where the spirits of those beautiful people have gone. I am reminded of these experiences when I look at Duncan’s photographs, and his work continues to inspire me.

I kept photographing even after these experiences, as many combat photographers have. We keep looking for pictures and following the battle, putting aside anxieties and telling ourselves it will be okay. The trauma hits later. Duncan’s photographs provide a quiet moment of reflection on a traumatic period of time we can all learn from, and will hopefully never experience. They remind me, and should remind all of us, of the importance of bearing witness. For this I thank you, David Douglas Duncan.

— Louie Palu