Here’s the plot of a story a writer told me he had joked about writing with Guy Davenport: For about two days in the 1970s, Queen Elizabeth, the Dalai Lama, and Thomas Merton were within twelve miles of one another in central Kentucky, about a mile from Lincoln’s birthplace. Merton lived at the Abbey of Gethsemani, the Dalai Lama was visiting him, and Queen Elizabeth was staying on a nearby farm where some of her horses were kept. In real life, the three never crossed paths, but in the story they do: “a tire blows out, there’s a great storm, their security details crash into each other on an icy road, they all wind up taking shelter in a barn somewhere. The trick would be figuring out the 4th person.” I was a graduate intern at the Harry Ransom Center, just beginning to assist with processing the final sections of correspondence in Guy Davenport’s papers, which the center had acquired in 2005, after the writer’s death. This month, the papers—letters, artwork, publications, and manuscripts by Davenport and others—are cataloged and available for research. Reading the collection’s finding aid—and seeing the incredible range of characters who considered Davenport a friend, mentor, or collaborator—the answer to the riddle of the fourth person is clear: it would be Davenport, of course, the shelter his home in Lexington, KY.

The Guy Davenport papers cover six decades of his life as a writer, scholar, painter, and intellectual. But the collection is especially noteworthy for the scope of its incoming correspondence. If Davenport’s own work never drew a popular audience, his letters at first blush would seem to suggest otherwise. The list of more than 2300 correspondents reads like a twentieth-century publisher’s rolodex: John Updike, Eudora Welty, Marianne Moore, Louis Zukofsky, Cormac McCarthy, Hugh Kenner, Joyce Carol Oates, Dorothy Parker, Ezra Pound, and on and on and on. Many of the exchanges span decades, including epistolary friendships begun as an admiring young writer’s shot in the dark.

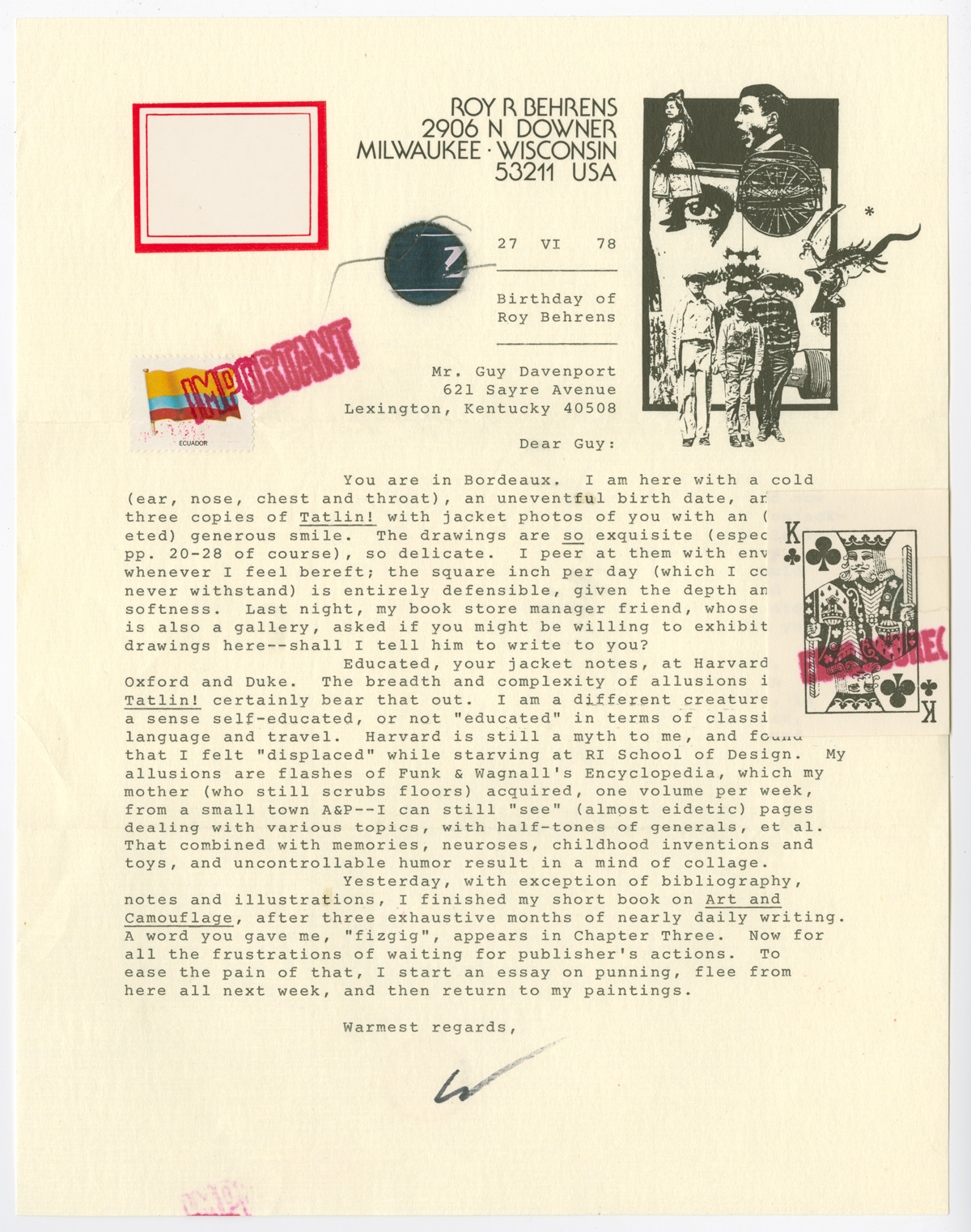

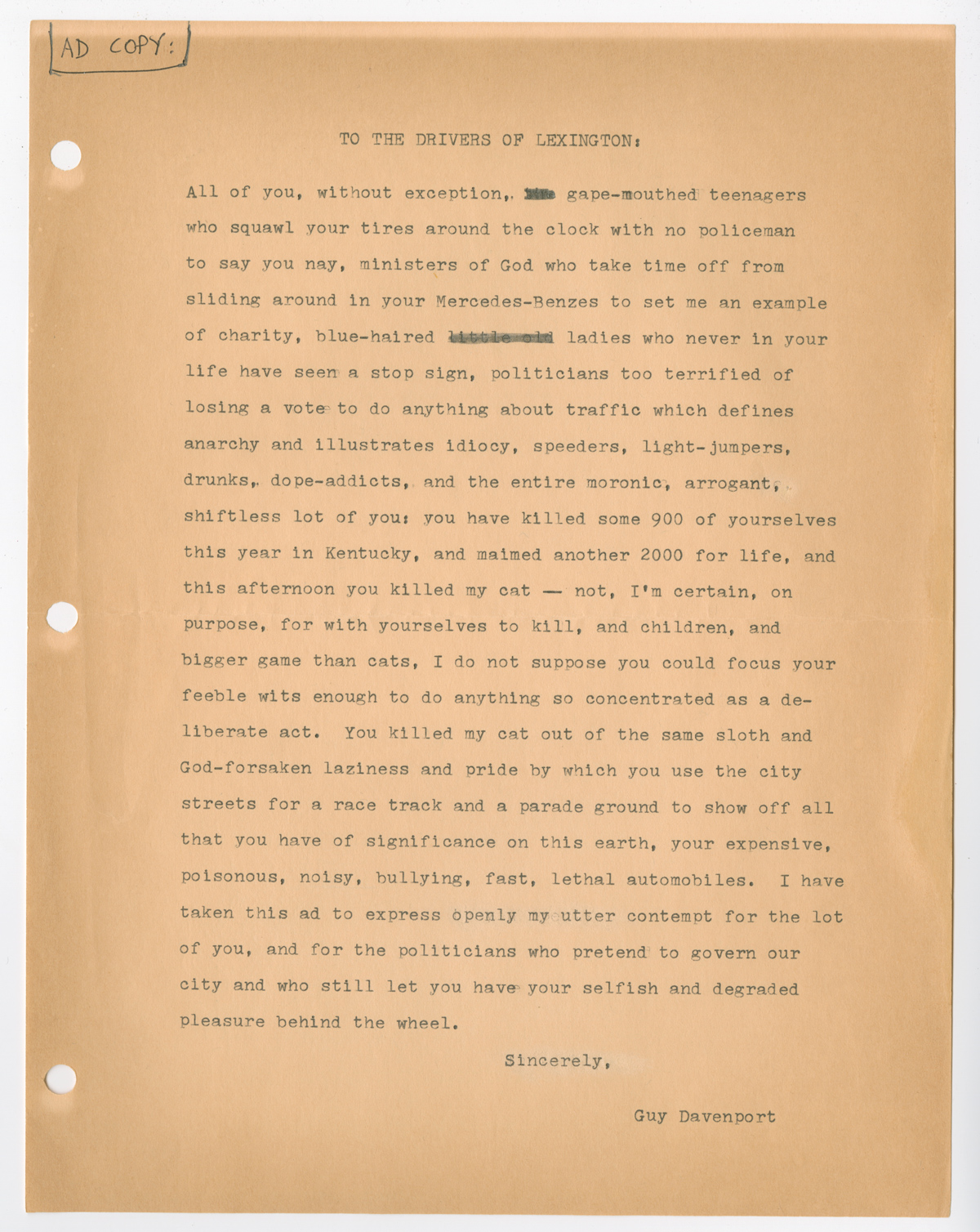

Because artists trusted and respected Davenport, their letters constitute smaller collections within the larger collection of papers and artwork that reflect Davenport’s work and life. Writers conferred with him about art—theirs and others’—between casual and intimate details about their days. They sent him their manuscripts at various draft stages, seeking the insight of a master, and for the most part took his comments—always honest, it seems, sometimes painfully so—with gratitude.

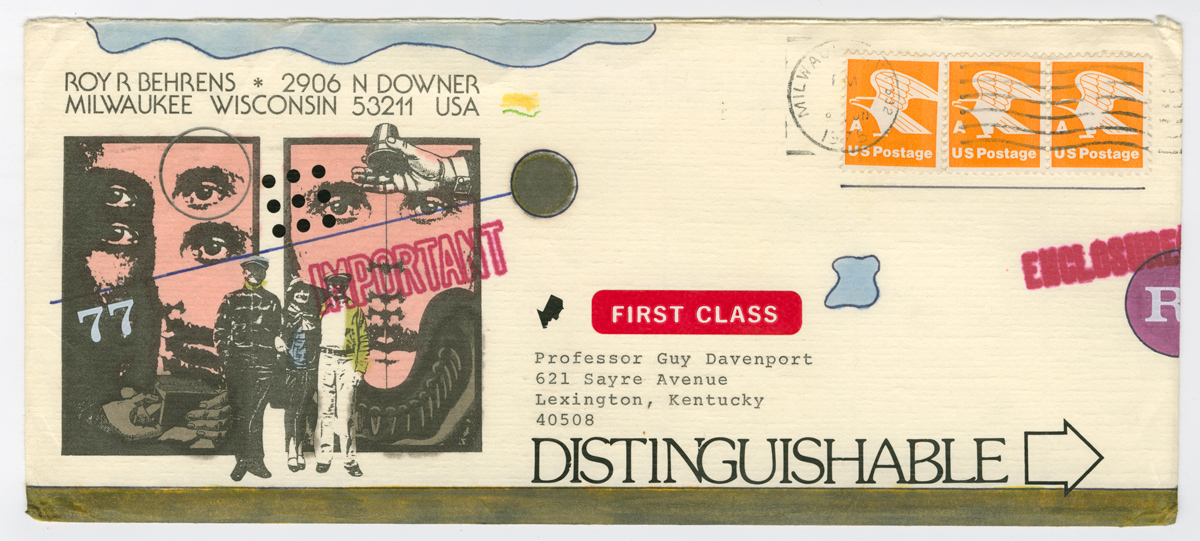

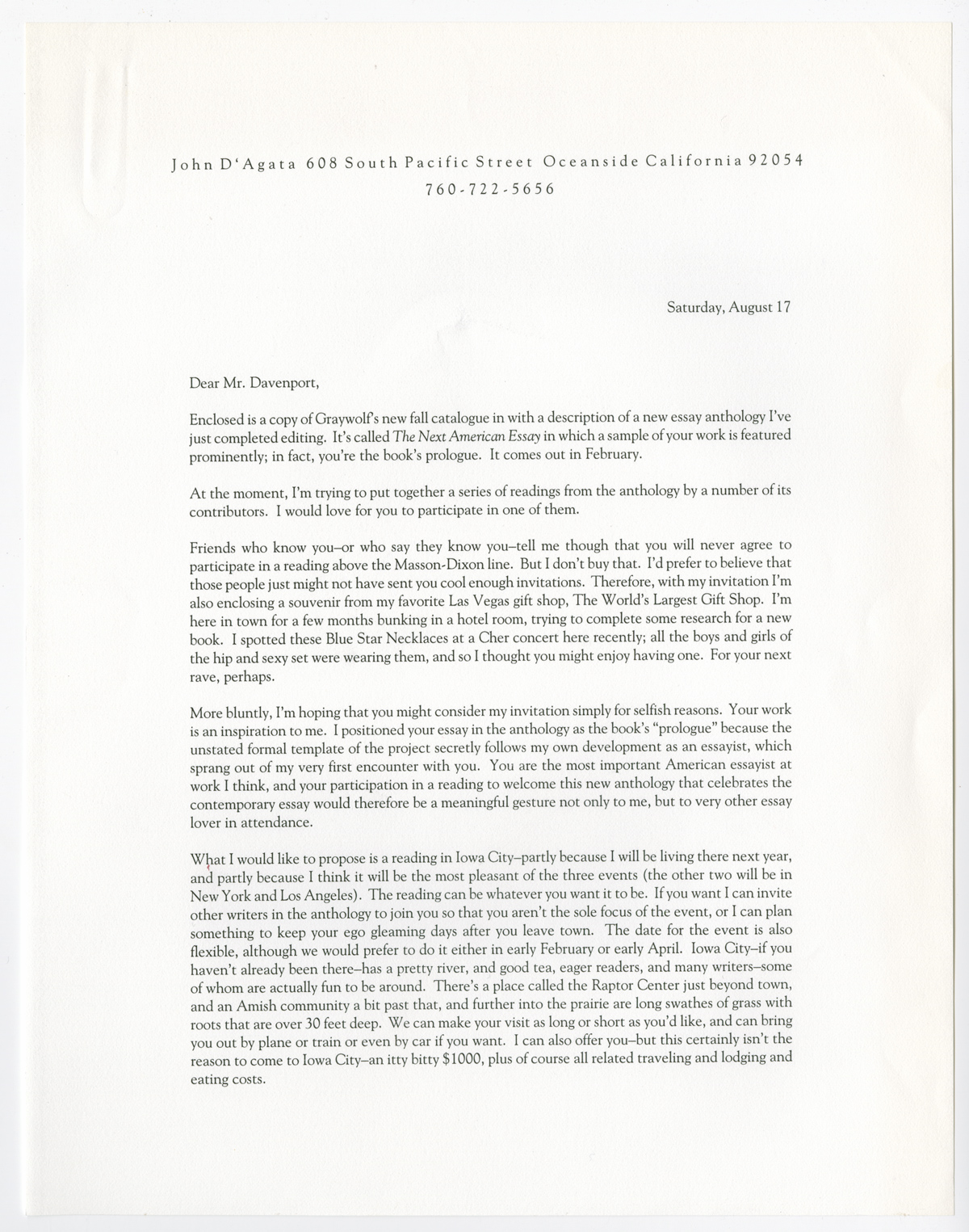

Davenport rarely saved copies of the letters he wrote, so reading others’ responses to him can feel like looking at the writer through a dark glass. I imagine him sitting down to write back to a young John D’Agata; the Southern poet and founder of The Jargon Society, Jonathan Williams; and some precocious student from a local high school in the same afternoon. How did he do it? Richard Workman, the archivist who processed the collection, tells me that Davenport recycled parts of his letters, passing anecdotes between his correspondents and on to his own work. His system for organizing the letters changed several times. First he used file cabinets, then letter boxes, grouping correspondence by the first letter of the writer’s last name. During the last decade of his life he simply tossed read letters into a box until it filled up, then started on another. Finally, he was ready to let himself rest, and replied with this letter:

Guy Davenport is no longer able to supply his hundreds of correspondents with blurbs, letters of recommendation, literary advice, invitations to visit, interviews, loans, or help with writing. He will continue as long as he can to correspond with friends but not with elbow-swingers, snoops, sneaks, and the personality-challenged.

He has given up writing. This is not a sharper turn into misanthropy and grouchiness, but illness and a longing for rest. He has been obliging for over 65 years. Write your own prefaces and introductions, even your own reviews (Whitman did, and Anthony Burgess). He apologizes (almost sincerely) for the inconveniences this shutting down of services may cause.

with absolute finality

[signed] Guy Davenport