“All the world’s a stage, and all the men and women merely players. They have their exits and entrances; And one man in his time plays many parts.” — As You Like It (Act II, Scene VII)

For four centuries, Shakespeare’s comedies, histories, and tragedies have held up a mirror to society, showing us our facility for both greatness and weakness.

Each staging of the Bard’s works leaves relics behind, and collecting those materials gives us a window on society at the time.

“Whenever Shakespeare is performed,” says the Ransom Center’s Eric Colleary, Cline Curator of Theater and Performing Arts, “there’s a reason why you do a particular production at a particular moment and how you stage it and what kinds of questions you are asking. How audiences receive it, or how critics receive it, speaks volumes about what’s going on in society at that particular moment. So it’s absolutely critical to be able to save and document these works.”

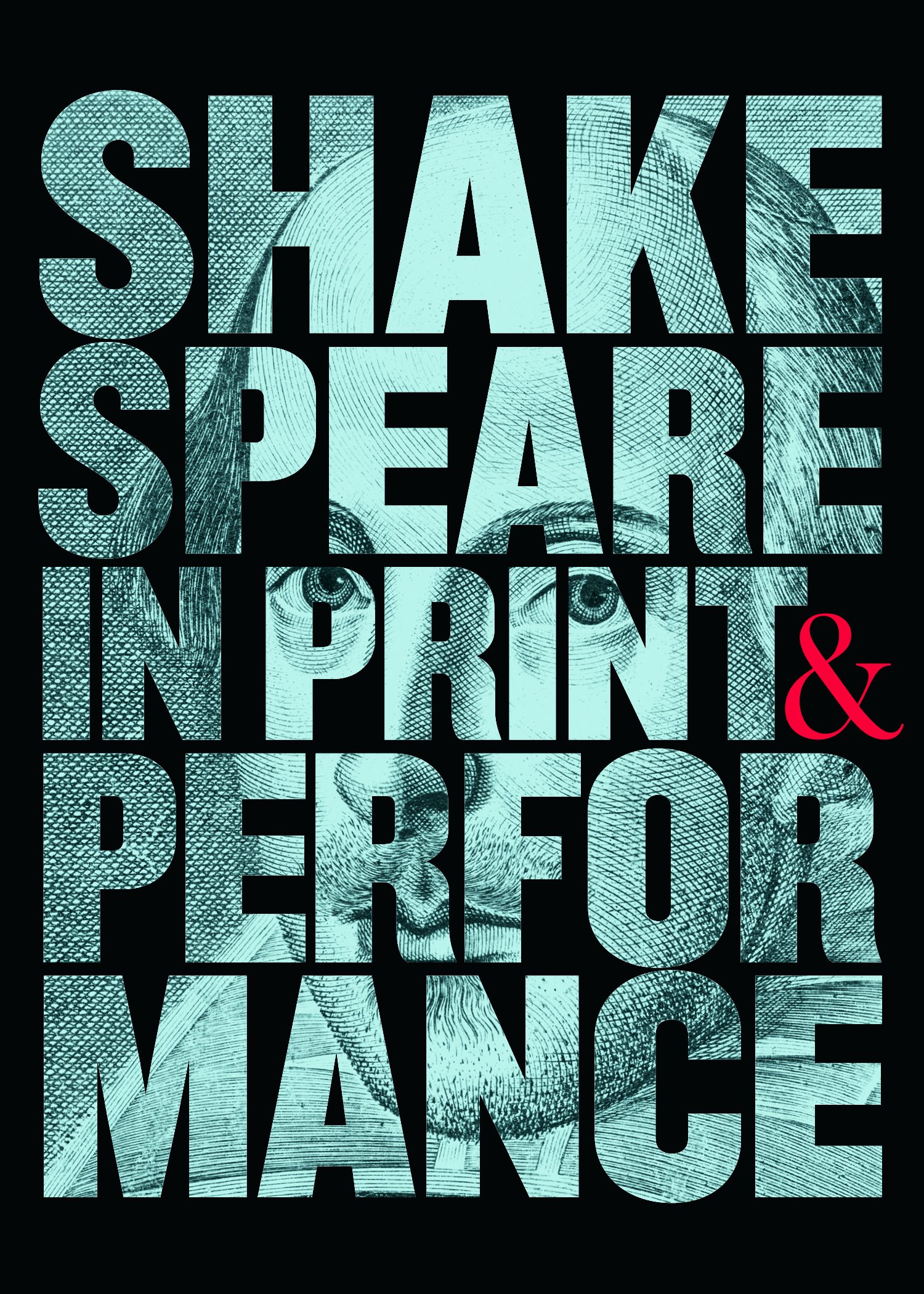

I talked with Colleary about the exhibition Shakespeare in Print and Performance, now on view.

“There’s so many different ways that Shakespeare can live in performance,” Colleary says, “so the exhibition is trying to showcase a lot of these using items from our collections.”

We discussed the materials left behind after a production ends, which the Ransom Center holds in its performing arts collection. Examples include scenic designs, costume designs, and other types of records. All of these objects tell stories not only about Shakespeare, but about the times in which the various works were staged.

“For me, and for many who do research in theater and performing arts,” Colleary says, “theater doesn’t exist in a vacuum. To be able to look at a particular production is a way of being able to capture—in that particular moment—what’s going on, how are people thinking about, for example, Shakespeare.”

The exhibition features several examples of scenic design, which he calls “works of art themselves, in addition to being documents relating to a particular production.”

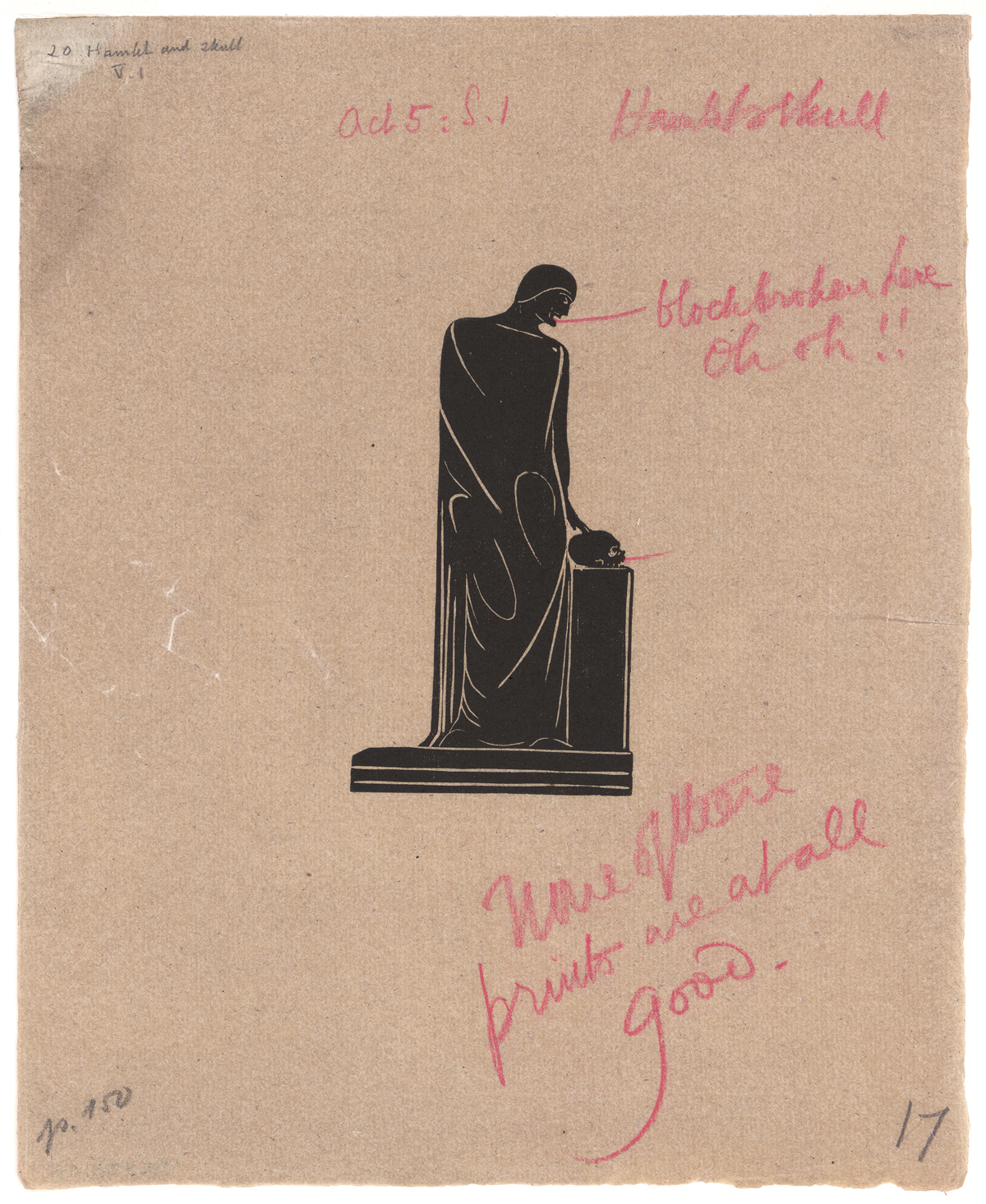

Designs for a legendary 1911 staging of Hamlet at the Moscow Art Theater by the Englishman Edward Gordon Craig are one highlight. The Ransom Center holds Craig’s papers. “His designs for Hamlet are some of the finest examples of Symbolist theater ever produced,” Colleary says.

In addition to the Ransom Center’s copies of Craig’s art book, the Cranach Press Hamlet, which features his designs in dramatic woodblock prints, set designs from the Moscow production are on display, loaned from San Antonio’s McNay Art Museum.

The exhibition also features Norman Bel Geddes’s 1917 designs for King Lear, along with the notes and illustrations he used for inspiration.

The exhibition’s costume design section includes a gown worn by Rosalind Iden as Beatrice, the heroine of Much Ado About Nothing. It’s part of the Ransom Center’s Donald Wolfit collection. Wolfit’s company toured the U.K. from 1936 to the early 1960s, performing Shakespeare—most famously during the Blitz, helping to keep British spirits up.

“Costumes are a really fascinating record of a production,” Colleary says. The Beatrice dress “was part of this company’s costuming collection for quite some time. And you can see repairs that were made to it because it was on stage so long. And it becomes an object record of all of these productions, all of these performances. That’s an incredible thing to have.”

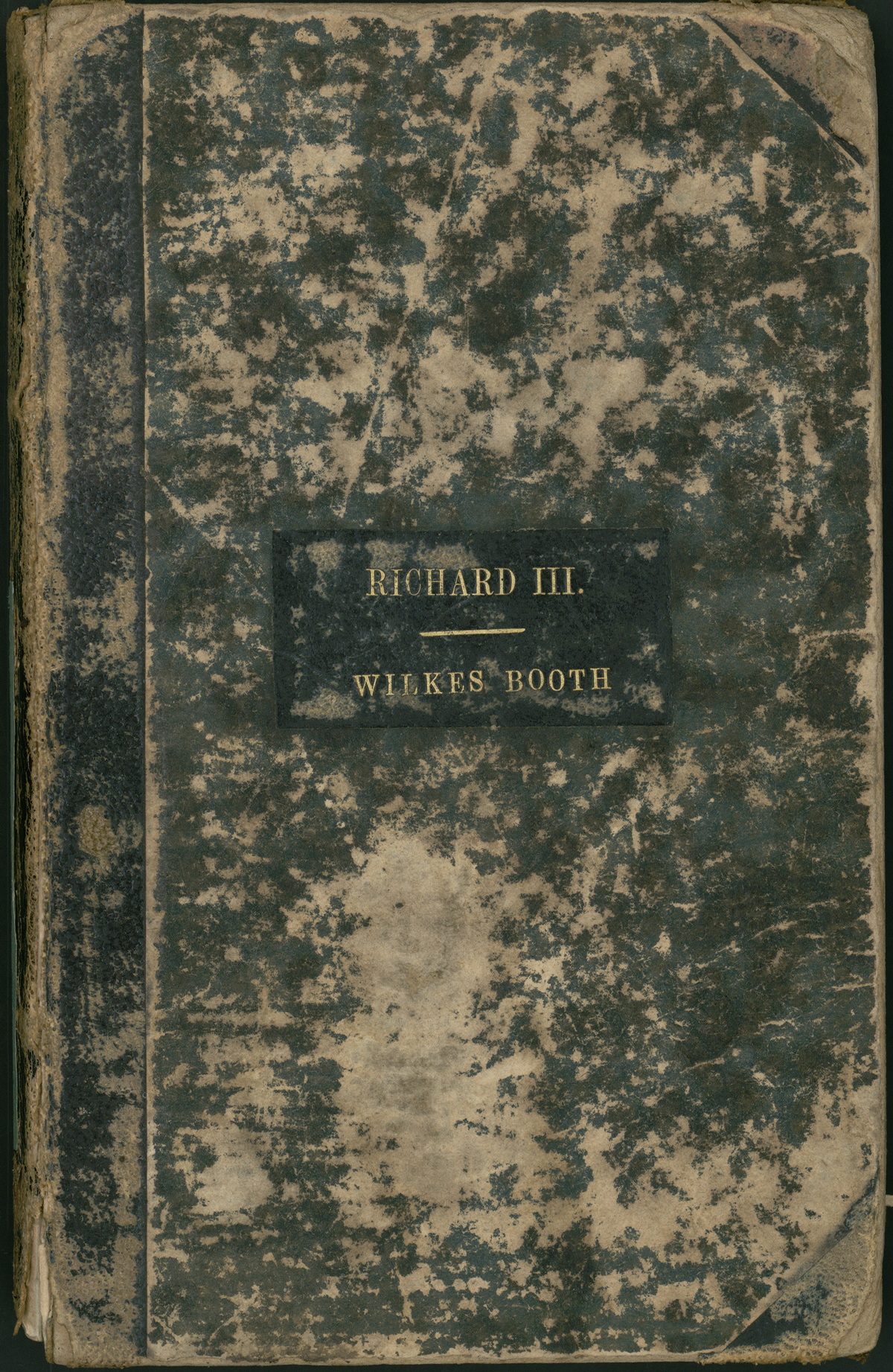

Finally, the performing arts side of the show features a selection of promptbooks. Colleary says that for the pre-film era, promptbooks provide “the best example we have of what a production looked like.”

A promptbook contains not only the script of a play, but also acting notes and technical cues, he said, like scene changes, lighting changes, and music.

The exhibition features six promptbooks, including one belonging to John Wilkes Booth, which Colleary says “is really quite incredible.” He notes that before Booth became infamous for his assassination of Abraham Lincoln, he was known for for his portrayal of Richard III.

Colleary hopes the exhibition will change how some visitors think about the Bard. “I have a sense that a lot of people’s experience with Shakespeare comes from classes from childhood, where they maybe came to Shakespeare in a really dry, unexciting way,” he says.

“I hope they come away from the exhibition realizing that Shakespeare is dynamic. It has incredible relevance to today. There’s so many different ways you can approach it. There’s so much inspiration that can come out of it.”

Shakespeare in Print and Performance runs through May 29.