Andrew Carlson, Clinical Assistant Professor and Managing Director of the Oscar G. Brockett Center for Theatre History and Criticism at The University of Texas at Austin, has worked extensively with Shakespeare’s plays through critical analysis and performance.

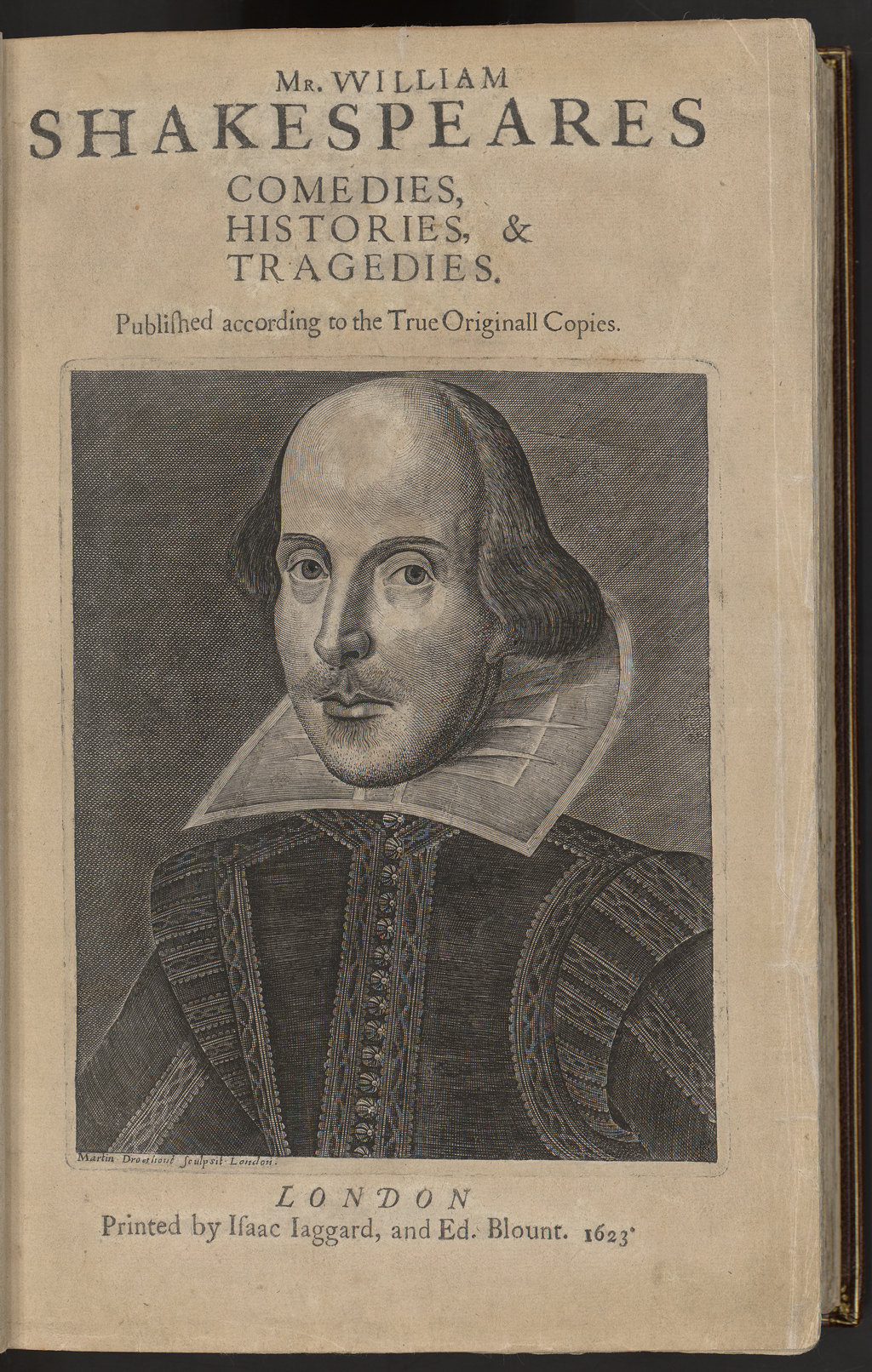

In the Ransom Center’s current exhibition Shakespeare in Print and Performance, three copies of the First Folio and many early play quartos are on view. The First Folio, a compilation of Shakespeare’s plays published in 1623, is generally accepted as the most authoritative of Shakespearean texts. Other texts, however, continue to vie for scholars’ and performers’ interpretive consideration. In addition to the First Folio, many quarto editions of Shakespeare’s plays have survived. Quartos are dubbed “good quartos” or “bad quartos” according to according to how well their text resembles the text of the First Folio and whether the publisher who issued it was authorized to do so.

On Tuesday, April 26 at 4 p.m., Carlson discusses how textual differences between folio and quarto texts of Shakespeare influence performance choices. The presentation includes a performance of two interpretations of the same Shakespearean scene.

Attendees may enter to win a copy of Andrea Mays’s The Millionaire and the Bard and a Shakespeare First Folio t-shirt. This program is free and open to the public, but donations are welcome. Seating is first-come, first-served, and doors open at 3:30 p.m.

In anticipation of Carlson’s lecture at the Ransom Center, we asked him to discuss his insights about Shakespeare’s works.

Your lecture will cover how textual differences impact performance in Shakespeare. What are some general ways that textual differences between folio and quarto texts of Shakespeare influence performance choices?

I’m always curious about claims of what it means for a text or performance to be “Shakespearean.” The folio/quarto discussion is a launching point for a larger conversation about the many factors that go into how we experience Shakespeare in performance. A performance of a Shakespeare play is not, as many theater practitioners argue, simply an act of “letting the text speak for itself.” I think Shakespeare is made, not received. The different extant texts of the plays reveal the constructed nature of the event, as do the myriad choices we make in performance. In my presentation, I will also put text and performance questions in dialog with the audience. The identity and values of the audience influence the meaning-making exchange that happens in performance.

Do you have a favorite Shakespeare play?

My favorite Shakespeare play is usually the one I am working on as an actor, dramaturg, or director. The deeper I get into it, the more I learn. Right now that play is Measure for Measure. It is a deeply troubling play that explores power, sex, justice, life, death, punishment, and religion. Those are some big themes.

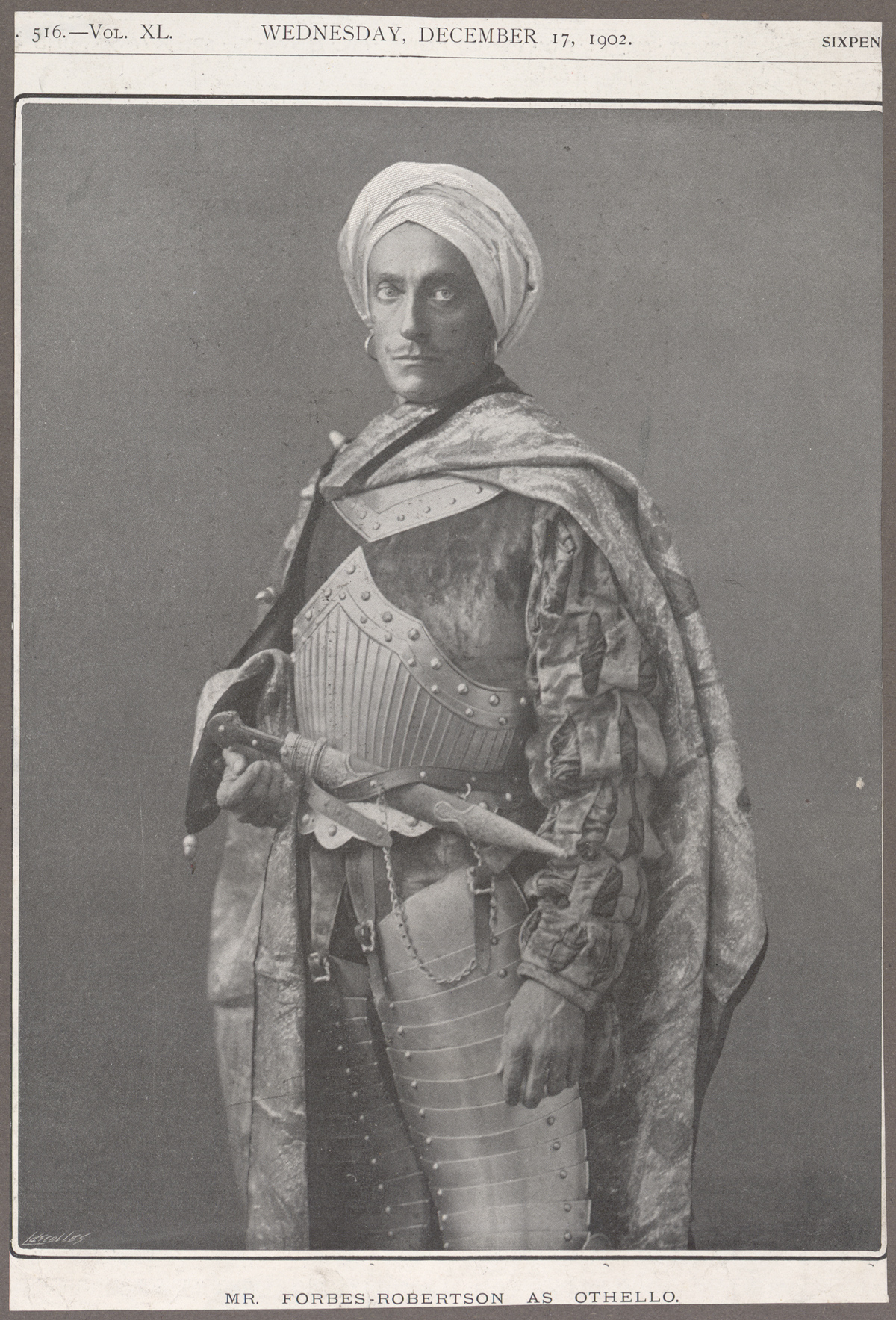

You also specialize in African American theater history. Could you describe the performance history of Othello, and the questions of identity and representation that it raises?

My research on Othello focuses on the play’s cultural and performance history in New York City. From its first performance in 1751, Othello has been a site for negotiating racial identities. By the nineteenth century Shakespeare was already constructed as the “universal” playwright whose plays spoke to the essence of humanity. But throughout the nineteenth century, “humanity” was hierarchically differentiated into increasingly hardened racial categories. The “legitimate” Shakespearean performance not only actively excluded African-Americans, but also defined his “correct” interpretation in opposition to constructed qualities of blackness. Many white critics argued that Shakespeare could not possibly have thought of Othello as a black character because he was noble and married to a white woman. However, there were many in the black community, including actor Paul Robeson, who said the exact opposite: Shakespeare intended Othello to be black because he believed in the equality of the races. The “Shakespearean,” then, was a construction that served other ideologies.

Today it is generally cast with an African American in the title role, but many wonder if that is such a good thing, or even if we should be doing the play at all. With this casting, it is the black Othello murdering the white Desdemona, fulfilling a stereotype of black male violence that has been part of the rhetoric of white supremacists for generations.

You also perform in plays and work with young actors as artistic associate for the Great River Shakespeare Festival in Minnesota. What are some common challenges you see actors encounter when performing Shakespeare?

I think actors often do a couple of things that prevent understanding. I know them well because I’ve done them both.

Sometimes we create this mumbled, faux-naturalistic Shakespeare that treats the language like it’s the same as talking to friends about whatever. The language is bigger than that, and the size of the thoughts requires more drive. It is often a cover for the fact that the actor doesn’t know what the words mean.

Or, more commonly, actors treat the language like it needs to be spoken at this high level of British emotional intensity. They put on a Shakespeare voice and play at the language, at their idea of what Shakespeare should sound like. I like to focus on understanding what the words mean and making the argument clear.