Responding to news of the singer’s passing in January 2016, the official NASA twitter account tweeted “Rest in peace, David Bowie. ‘And the stars look very different today.’” For Bowie, one of humankind’s hitherto unanswered questions was—to quote from his most famous song—“(Is there) Life on Mars?” In this vein he followed in the footsteps of H. G. Wells, another popular culture icon who was among the select few featured on the cover of The Beatles’ “Sergeant Pepper’s Lonely Hearts Club Band” (1967).

Both Bowie and Wells grew up in a London suburb, Bromley. Wells was also born there. Both could not wait to escape from suburbia. Both used talent and imagination through art as part of the process of leaving behind their past. Thus, when writing about Bowie, Simon O’Hagan argued that this “explains how, in so many of his songs, the reality of his suburban upbringing co-exists with themes of outer space.” For O’Hagan, “Bowie was in some ways the H. G. Wells of the jukebox.” Renowned for his bestselling science fiction stories and their audio-visual adaptations such as by Orson Welles and Steven Spielberg, Wells not only wrote serious newspaper articles about life on Mars but also incorporated Martians into his fiction juxtaposing fantasy scenarios with suburban realities.

Since landing on Mars in August 2012, NASA’s robot rover has been exploring the Red Planet to try to help answer the question posed by Bowie and Wells, among others. Unsurprisingly, NASA’s Mars Curiosity Project has attracted extensive world-wide media coverage, particularly given the manner in which myriad works of science fiction have both reflected and encouraged our fascination with Mars, Martians, and all that. At present the jury is still out concerning life on Mars, but this has not prevented continuing speculation that, given our present-day surveillance society, we have been, and still are being, watched from Mars. In The War of the Worlds (1898), Wells introduced the idea that, like bacteria under a microscope, people on Planet Earth were being studied by Martians by way of preparation for the first interplanetary war. He made plausible—or at least not out-of-this-world—the possibility of extra-terrestrials acting as spies, invaders, and empire-builders.

The War of the Worlds’ prescience and afterlife

As a result Wells, like Bowie, occupies a prominent place in our present-day thinking about Mars, as evidenced by his prominent role in, say, NASA’s online “Mars chronology” or the press kit prepared for the launch of the Mars Rover in 2011. Today, Wells’s ghost still looms large over popular attitudes and contemporary media debates about the Red Planet. In part, this reflects the enduring fame of The War of the Worlds as—to quote Robert Crossley—“a central text in the cultural history of Mars.”

Written during the late nineteenth century and set during the early twentieth century, The War of the Worlds continues to attract readers and resonate with audiences during the twenty-first century. For most readers, the story is just an excellent read, an exciting sci-fi page-turner. But its enduring appeal derives also from a timeless focus upon the impact of invasion and war upon present-day society through a storyline touching upon such perennial themes as complacency about homeland security, the need to take account of the unexpected, the ferocity of aggressive imperialism, the devastation and mass panic prompted by sudden invasions, and the impact of science and technology upon warfare and weaponry.

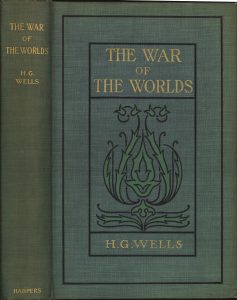

The War of the Worlds remains in print, still sells well, and has been translated into numerous languages. Moreover, the book has enjoyed an extremely successful multimedia afterlife. Thus, Wells’s pioneering story has been taken, and continues to be taken, to new audiences across the world through adaptations, most notably on film by George Pal (1953) as well as by Steven Spielberg and Tom Cruise (2005), on radio by Orson Welles (1938), and through music and stage rock operas by Jeff Wayne (1978 et seq.). The story’s subject matter, most notably its massive potential for vivid imagery, has made The War of the Worlds a focus also for bubblegum and cigarette cards, comics, computer games, e-books, graphic novels, mobile phone apps, and podcasts, among other outputs.

Wells as “the Shakespeare of science fiction”

For most people, and particularly the media, the big literary event in 2016 is the 400th anniversary of William Shakespeare’s death. But this year also marks two Wellsian anniversaries, that is the 150th anniversary of Wells’s birth and the 70th anniversary of his death. Hitherto these Wellsian anniversaries have attracted far less media and popular attention, even if they are—to quote Durham University’s Professor Simon James—“every bit as important as that of Shakespeare. His novels The Time Machine, The Invisible Man and The War of the Worlds were the first true science fiction novels in the English language.” Indeed, Brian Aldiss, the science fiction grand-master, has represented Wells as “the Shakespeare of science fiction,” the author largely responsible for inspiring and popularizing science fiction, particularly the alien invasion and time travel sub-genres. For many commentators, Wells is viewed as a prime source of inspiration for Gene Roddenberry’s Star Trek films and television series, while BBC television’s time travelling Doctor Who proves a straight steal based upon the Time Traveller in The Time Machine.

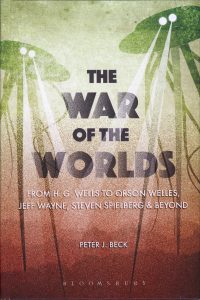

My book

Bloomsbury Academic has just published my book entitled The War of the Worlds: from H. G. Wells to Orson Welles, Jeff Wayne, Steven Spielberg and beyond. I have lived in Woking, a town situated 30 miles southwest of London, for over 40 years, and was first drawn to The War of the Worlds when learning that Wells researched and wrote the story while residing in Woking during 1895–1896. Serialized by Pearson’s Magazine (1897) in Britain and across the Atlantic by Cosmopolitan (1897), the New York Evening Journal (1897–1898), and the Boston Post (1898), The War of the Worlds was published as a book in London and New York in 1898. Set in Woking, the story was told by a narrator resident therein. Horsell Common, located on the town’s outskirts a mile or so from my own house, became the site of the Martian landing and the battleground for the first interplanetary war. In 1938 listeners of Orson Welles’s radio adaptation—this moved the setting to the USA—reported fears that Martians had just landed in their backyards! Reading the book for the first time, the skillful manner in which Wells juxtaposes fantasy storylines with real places led me to believe that the Martians might well land in my garden!

Originating as a local history project focused upon Wells’s stay in Woking, my book, drawing upon archival research conducted in both Britain and the USA, expanded gradually into a biography of The War of the Worlds as a book: its inspiration, research, writing, reception, and multimedia afterlife. Wells’s correspondence held by the Harry Ransom Center at The University of Texas at Austin proved a principal research source yielding invaluable insights into his personal life, early career as a new young writer—it is easy to forget that he was only 28 years old when he published The Time Machine—and the writing of The War of the Worlds.

Research revelations from the Harry Ransom Center

At the Ransom Center Wells’s correspondence with Elizabeth Healey, a longstanding confidante dating back to their student days, casts light on:

- the breakdown of his first marriage and divorce;

- the affair with Amy Catharine Robbins, who became his second wife;

- residential mobility;

- favorite forms of leisure, especially boating, cycling, and walking; and

- ill health resulting in genuine expectations of an early death with only a few books lying between him and the grave.

The Healey letters illuminate also Wells’s efforts to make his way in the challenging literary world, including:

- his growing impatience with initial difficulties in securing publication, fame, and money;

- the sudden transformation in his fortunes consequent upon the highly positive reception and sales secured by The Time Machine (1895), his first fictional book;

- reluctant acknowledgement that such “pseudo-scientific” stories were the best way to make his mark; plus

- a fundamental desire to move on quickly from scientific romances to write mainstream novels—this was exemplified by Love and Mr Lewisham (1900)—to show that he “was no charlatan.”

Further elaboration of these points, particularly concerning Wells’s relations with publishers, is provided by his correspondence with James Brand Pinker and William Morris Colles, two of his literary agents. From an early stage of his writing career Wells employed literary agents, then a relatively new role, to reinforce his own efforts to secure contracts for books and serializations thereof as well as to facilitate negotiations with foreign publishers. These letters reveal the problematic nature of Wells’s relationship with publishers resulting from his prickly personality, confidence in the scientific romances’ marketability, resulting anxiety to squeeze as much money as possible from his work, and an “us” and “them” mentality as regards writers and publishers.

William Heinemann published The Time Machine, The Island of Dr. Moreau, and The War of the Worlds, but was repeatedly criticized by Wells for lackluster marketing, frequent demands for more words, mispricing, and low advances. For example, in July 1898 when conducting negotiations about the advance for When the Sleeper Awakes Heinemann accused Wells of failing to understand bookselling realities. Responding that authorship was not intended merely to reward publishers, Wells gave Heinemann an ultimatum: “it’s £750 or nothing.” Heinemann refused to give way. Wells walked away, and never published with Heinemann again.

Of course, my book includes much more from the Ransom Center archives, but there is space only to mention one more letter, which was written by Wells to a Mrs. Tooley in 1908. Apart from providing a brief biography, Wells outlines his writing methods and the manner in which his fiction, though not autobiographical, made use of all his personal experiences. In addition, he stressed that his serious health problems were now all in the past.

Celebrating “Wells in Woking 2016”

Notwithstanding its importance for The War of the Worlds, Wells’s residence in Woking proved the most productive period in his whole writing career. Indeed, the modest semi-detached house he rented in Woking became a kind of “literary factory.” Here he completed also The Island of Dr. Moreau, wrote and published The Wonderful Visit and The Wheels of Chance, wrote The Invisible Man, and began writing When the Sleeper Wakes and Love and Mr. Lewisham.

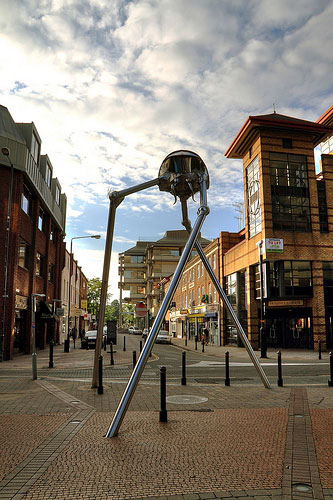

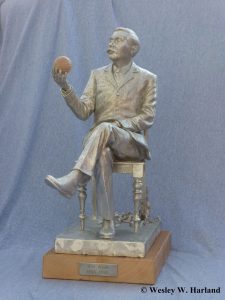

Against this background, Woking is hosting a series of events (http://www.celebratewoking.info/wellsinwoking) throughout 2016—for example, in July the H. G. Wells Society held its annual conference in the town’s H. G. Wells Conference Centre—to celebrate the above-mentioned anniversaries. In September I shall be drawing on my research conducted at the Ransom Center when giving the 2016 Surrey Heritage Lecture on “Wells and Woking: the literary heritage” at the Surrey History Centre. A few days later Woking’s “The Martian” sculpture, erected in 1998, will be joined nearby by the first ever sculpture of Wells himself.

Peter J. Beck, Emeritus Professor of History at Kingston University, Kingston upon Thames, UK, is the author of The War of the Worlds: from H. G. Wells to Orson Welles, Jeff Wayne, Steven Spielberg and beyond, which was published by Bloomsbury Academic in August 2016. His other books include Presenting History: Past and Present (2012), Using History, making British Policy: the Treasury and the Foreign Office, 1950-76 (2006), and Scoring for Britain: International Football and International Politics, 1900-1939 (1999).