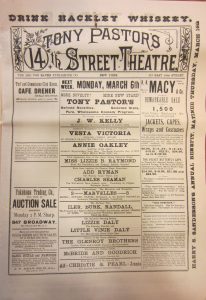

The bottom half of this postcard—one of many images in the Harry Ransom Center’s Tony Pastor collection—reveals a lot about the early days of vaudeville.

It shows Pastor’s New Fourteenth Street Theatre in New York City, where he moved uptown in 1881 to initiate what was called “polite vaudeville.” It shows the price of seats (20 cents and 30 cents); the promotion of a “continuous show” (which allowed women to use vaudeville as a break between shopping expeditions or even as a kind of drop-in child care); and the giant playbills posted on the street front (promoting Irish skits, dialect comedians, singers and dancers of many nations, blackface duos, and Tony Pastor’s name looming largest of all). After two months in the archive, however, my eyes are insistently drawn way up, above the building’s cornice, to a detail less often noticed in this context: an Indian. This is the seventeenth-century Delaware leader Tamenend, made over as patron saint of the Tammany organization, in whose building Pastor’s theater was lodged. The statue tells us that vaudeville was literally invented under the sign of the Indian.

That is not the usual depiction of vaudeville. Indeed, vaudeville is hardly ever discussed as a venue for Native performers of the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, who are almost automatically associated with Wild West shows. The image of howling warriors on horseback does not fit the snappy, modern novelty, the virtuosity and variety of vaudeville: unruly women singers, African American tap-dancers, Jewish comedians, Arabian fire eaters, Irish parlor tenors, Japanese tumblers, dog and monkey acts. The large collection of Tony Pastor materials shows that Indians were hard to find on his stages.

![Unidentified photographer, [Dorothy Deer Horn in Thais], 1931. Gelatin silver print, 10 x 8 inches, recto. New York Journal-American Photographic Morgue, Harry Ransom Center](http://sites.utexas.edu/ransomcentermagazine/files/2016/10/PA_New_York_Journal_American_Photographic_Morgue_Deer_Horn_Dorothy_001-241x300.jpg)

“Indian” acts and Indian performers

But there were both “Indian” acts and Indigenous performers in vaudeville, and they lurk on the highways and byways of the Center’s archives, visible if you look hard enough across enough different collections. Publicity photographs, cabinet cards, newspaper images, press clippings, advertisements, programs, playbills, posters, theaters’ organizational records, correspondence, and other papers offer up a fragment of identity in one place, a contrasting perspective in another, sometimes a contradictory detail in a third. Some figures are well known—the Jewish Fanny Brice playing Indian, the Cherokee Will Rogers playing cowboy—but more are largely forgotten. Take, for example, Princess Deer Horn, who claimed—as so many did—to be “a direct descendant of Pocahontas” and alternated between “Indian interpretative dances” and modern dances in vaudeville. Her publicity photographs in the Theater Biography Collection show her strutting her stuff—the smile, the pose, the outfit—for audiences and impresarios.

![Unidentified photographer, [Dorothy Deer Horn in Thais], 1931. Gelatin silver print, 10 x 8 inches, verso. New York Journal-American Photographic Morgue, Harry Ransom Center](http://sites.utexas.edu/ransomcentermagazine/files/2016/10/PA_New_York_Journal_American_Photographic_Morgue_Deer_Horn_Dorothy_002-244x300.jpg)

![Charles Eisenmann (American, 1855–1927), Untitled [Inscribed verso: “Yan-a-Wah-Wah, Indian Princess and Child Rescued from one of the South Sea Islands by a Sailor”], ca. 1885. Albumen print (cabinet card), 6 ½ x 4 ¼ inches. Circus Collection, Harry Ransom Center](http://sites.utexas.edu/ransomcentermagazine/files/2016/10/PA_Circus_Collection_circa_1775_1988_Series_IV_Dime_Museums_28_001-207x300.jpg)

As Pastor moved from the circus to the Bowery to variety to uptown vaudeville, he gradually cut the Indian acts on his playbills. Building “polite vaudeville” as a family-friendly venue meant not only excising the alcohol, the double-entendres, and the rowdy audiences; it also meant leaving behind Indians as oddities and freaks who didn’t belong to gentility and modernity. But the Tammany Hall lodgings meant that Indianness continued to saturate the environment, as Pastor’s scrapbooks show: vaudeville audiences entered under the benignity of Tamenend’s outstretched hand and into a building popularly known as “the wigwam,” in which, every Christmas, Pastor co-hosted “a big powwow.” Indeed, the impresario whose name and image loomed so large over the whole spectacle was sometimes billed “the Christopher Columbus of vaudeville talent.” When, in the early 1900s, Pastor began to struggle to maintain his lead over the competition and sought to inject novelty into his program, he reached back into the dime museum repertoire for Indian acts that might make the difference.

From vaudeville to modernity

If going back in time helps to return popular Indigenous performers to visibility, so does going forward. Pastor’s collection—given his status as “the father of vaudeville”—constitutes something of a starting point for the study of this entertainment form. Two other collections at the Center, the Florenz Ziegfeld collection and the Florenz Ziegfeld photographs collection, constitute a kind of endpoint. As vaudeville waxed and waned, Ziegfeld rang the changes once more, upping its format to a revue of more lavish style, higher prices, and better-heeled audiences. Immediately, Indians returned to view. The first ever Follies of 1907 was emceed by Pocahontas—“big in the cigar trade”—played by the non-Native Grace LaRue. Soon faux Indians were joined by Native performers whom Ziegfeld hired off the vaudeville stage: Will Rogers (Cherokee), Princess White Deer (Mohawk), and Chief Caupolican (Mapuche), among others. The full efflorescence of Indianness came in 1928 with Whoopee! and its mass of parodically oversized head-dresses, skimpily clad chorus girls on horseback, Jewish Eddie Cantor in redface, and Chief Caupolican in powerful opera voice. From Tamenend gesturing atop the building to Caupolican serenading the setting sun on stage is less distance than you might think: versions of Indigeneity run through the history of vaudeville, an unacknowledged undercurrent of desire, display, and skill, always, ultimately, undergirded by Native power.

Indigenous vaudevillians belong to the larger “secret history” of Native peoples making popular culture that Dakota scholar Philip Deloria, in Indians in Unexpected Places, names as a central plank of modernity and that are so deeply buried that they are not to be found neatly gathered in a single archive. The rich unpredictability and diversity of the Center’s holdings are invaluable in recovering forgotten lives: the very ways in which these figures go in and out of focus—appearing and disappearing from one collection to another, sometimes in control of their own image-making, sometimes at the mercy of others, sometimes isolated within a theatrical frame, sometimes situated within society at large—give a sense of the challenges and complexities they faced in trying to get a foothold as itinerant entertainers. Moving beyond the containment of display to the relative autonomy of vaudeville employment was one strategy of what, in Manifest Manners, Anishinaabe scholar Gerald Vizenor names “survivance” in a period generally recognized as the nadir of government regimes, genocidal policies, and starvation conditions for Native peoples. These recovered lives—partial and tantalizing as they may be—also challenge dominant performance histories and, because vaudeville is widely considered central to the making of modernity, provide one more chapter to the rapidly changing story of Indigenous peoples’ roles in that process.

Christine Bold is a professor of English at the University of Guelph in Canada. Her publications include six books on popular culture, cultural memory, and the WPA writers’ project, most recently the award-winning The Frontier Club: Popular Westerns and Cultural Power, 1880–1924 (Oxford UP, 2013). She thanks the Ransom Center for its incomparable support—including administrators, reading room staff, and curators (most especially Eric Colleary)—during her research fellowship, May to June 2016.