Elizabeth Olds (1896–1991) was the first woman visual artist to be awarded a Guggenheim Fellowship in 1926 to advance her study of portraiture. From Minnesota, Olds studied at the Art Students’ League of New York where she worked with the realist painter George Luks in the early 1920s. She traveled in Europe from 1925–1929, sketching and performing with a French family circus-troupe, and viewing some of the world’s most influential works of art, ranging from Renaissance sculpture in Italy to Post-Impressionist works in France.

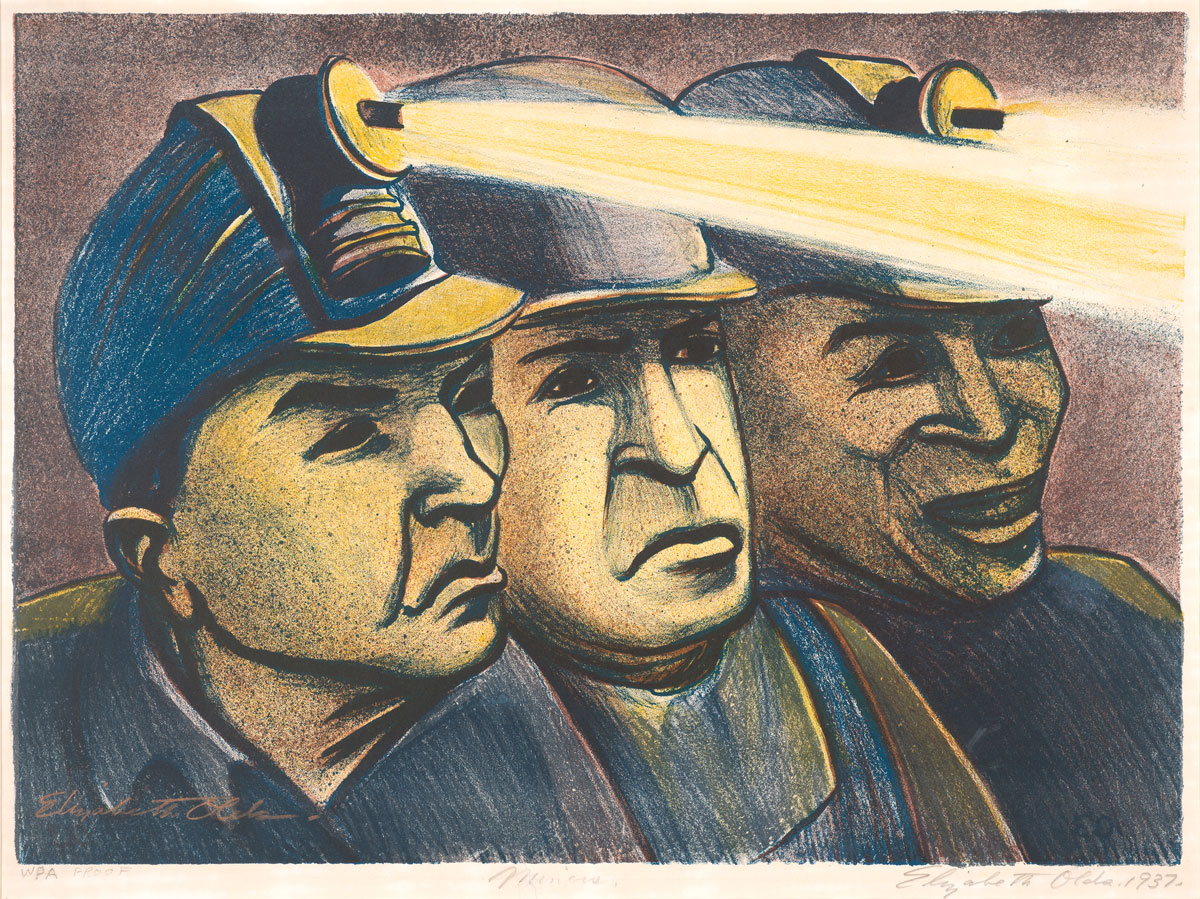

Returning to the U.S. at the start of the Great Depression, in 1932 Olds accepted a portraiture commission from industrialist Samuel Rees and moved to Omaha, Nebraska, where she learned lithography at Rees’s printing business. Olds joined the Public Works Art Project (PWAP) in Omaha in 1933, and is quoted in the Omaha World Tribune in 1935 as saying that she, as part of a larger group of contemporary artists, chose “to find [her] subjects on the streets, in the factory, the machines and workers of industry on the farms.” She encouraged the American public to “cast aside outworn pictures as ‘decoration,’ and… put instead on their walls a reflection of life as vital as they themselves are.” Despite her studies in Europe, Olds came away from the experience with a desire to create something honest: art that depicted life, with all of its misery and unfairness, as it truly was.

Displayed in the Stories to Tell exhibition are some of Olds’s most striking pieces from this era. She had a talent for quick sketching and translating those sketches to lithographs. Her depictions of men sharing a bunk, as seen in Flop House (1930s), and eating at shelters, like in Salvation Army Shelter (1931), convey a sadness and despair that was specific to the time, but nearly universal amongst working-class men. There is a sense of exhaustion emanating from these pieces that speaks to the general mood of the Depression Era.

Olds’s later lithographic pieces are even more striking, particularly for their sense of urgency and satirical treatment of white collar workers—many of whom escaped the worst of the Great Depression at the expense of the working classes. Olds was a contributing artist to Roosevelt’s Federal Arts Project, and her pieces served as a reflection of the state of American society. Her fondness for Mexican muralist painters, particularly José Clemente Orozco, is apparent in her social realism style, including her work 1939 AD. In contrast to her real-life sketches, this piece is a commentary on the class conflict between blue and white collar workers. Olds’s depiction of Jesus cracking a whip on the capitalists of Wall Street paints the blue collar workers—marching for “Democracy,” “Social Equality,” “Social Security,” and “Right to Work”—as his humble supporters and the white collar bankers as demons possessed by a love of gold.

A selection of Elizabeth Olds’s work is currently on display in the Ransom Center’s Stories to Tell exhibition. The Ransom Center also holds original works, correspondence, and photographs relating to Olds.