Coming Out of the Archives is a selection of materials curated by students in my spring 2017 Queer Archives class. The materials can be seen in the Ransom Center’s Stories to Tell exhibition that features rotating highlights from the collections. [Editor’s note: the items are no longer on view, as the display cases have rotated]

Housed in two cases alongside Edgar Allan Poe’s desk and José Guadalupe Posada’s broadside prints, the materials focus on the affective and social networks that link those with LGBT and/or queer sensibilities who are present not only in the art world but in the Center’s holdings.

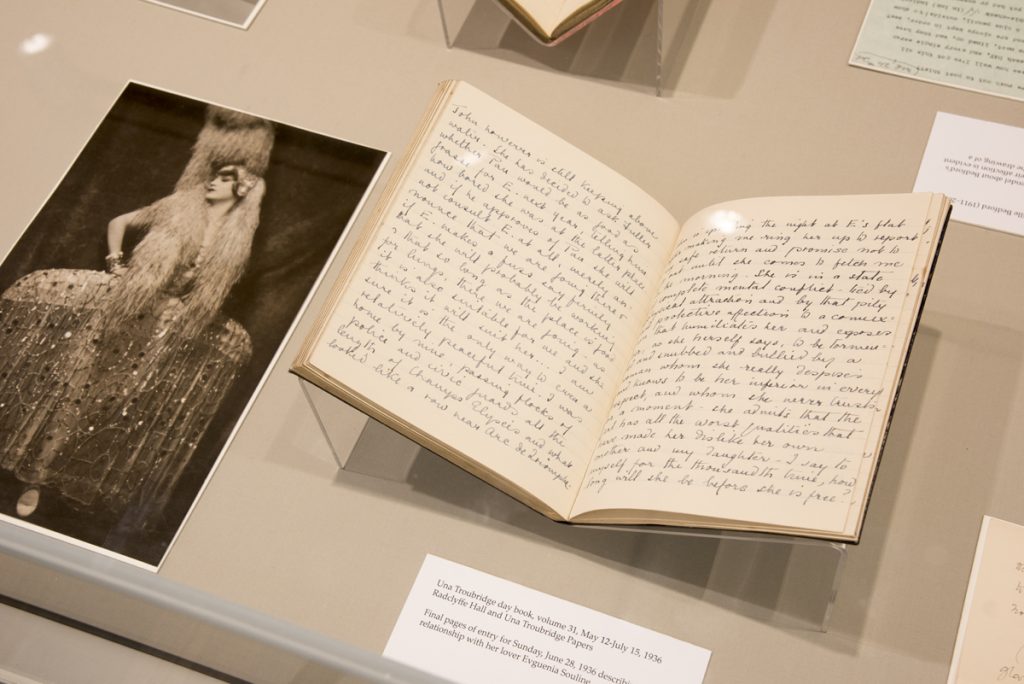

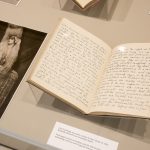

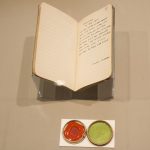

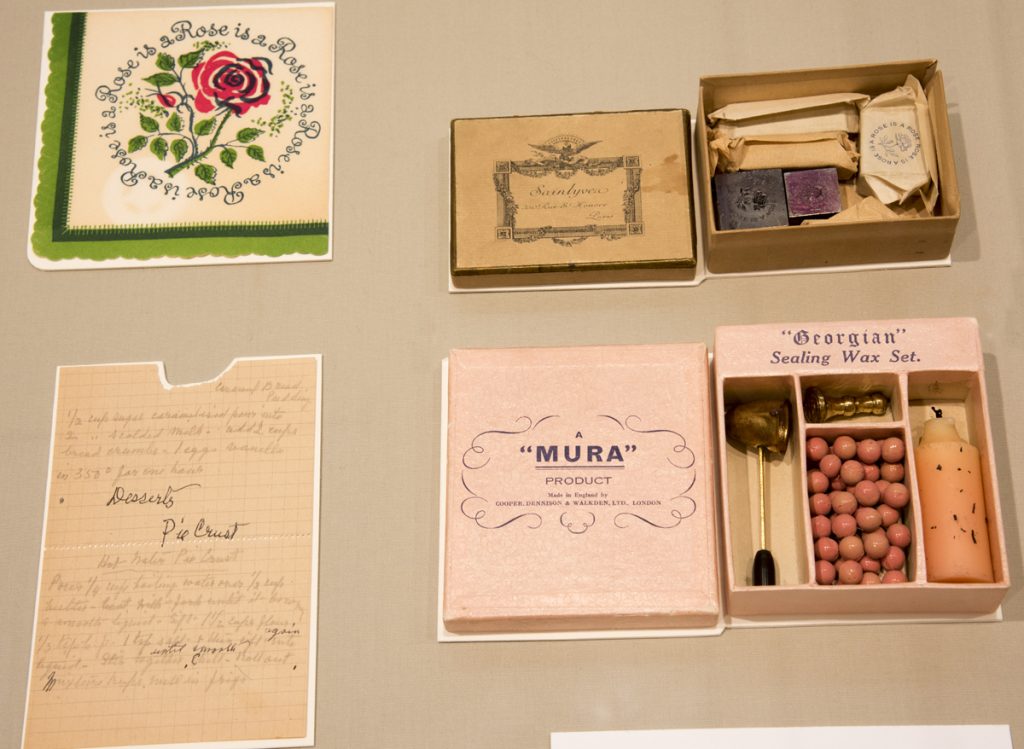

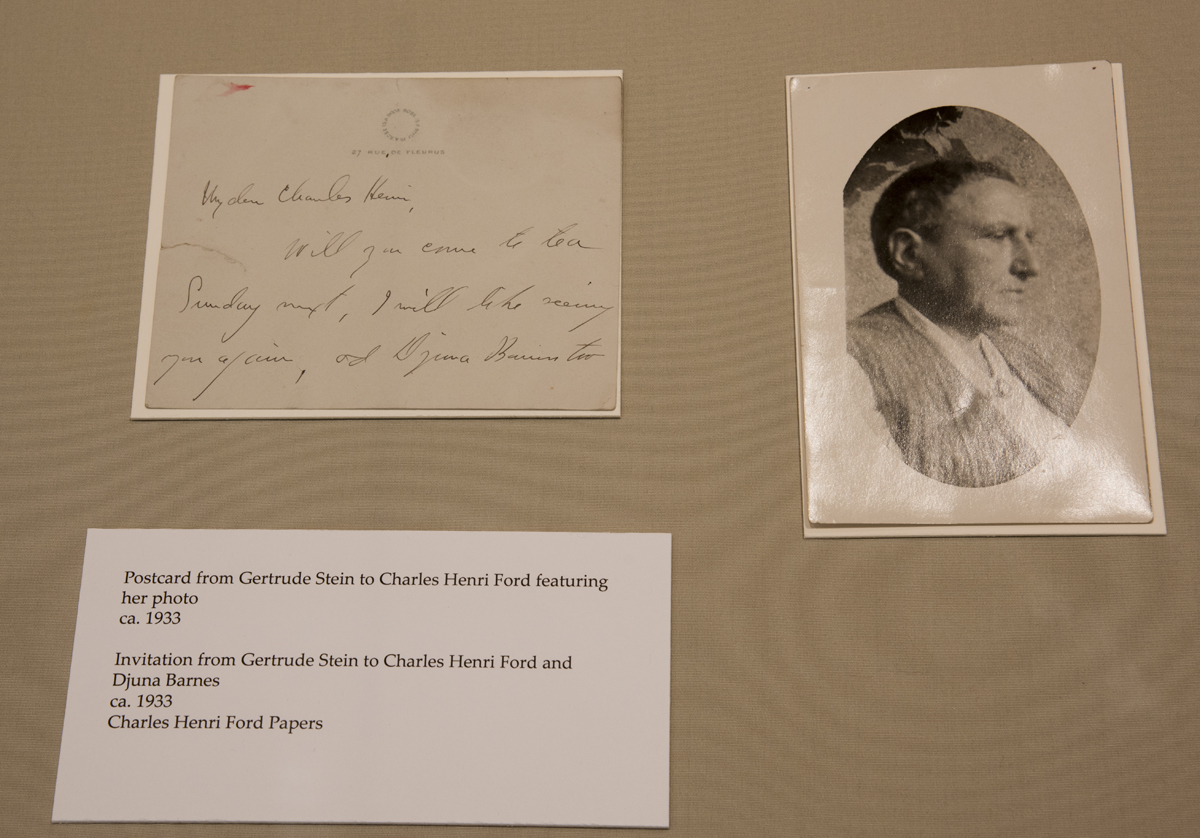

You can see household ephemera from Gertrude Stein and Alice B. Toklas’s famous salon, photos and press clippings about Radclyffe Hall and Una Troubridge’s prize-winning show dogs, and letters recording personal and professional intimacies between the famous and not-so-famous, and learn more about Texas’s own Barbette, a performer who toured Europe, especially Paris, in the 1920s and 1930s.

The display is the result of a collaboration with the Ransom Center’s Head of Instructional Services Andi Gustavson, who encouraged me not only to get the students into the reading room to do original research but to curate items for exhibition by the end of the semester.

Not having done either before—I’ve sent the students to the Ransom Center for single class assignments but never based a class there, and I’ve also never curated an exhibition myself, much less tried to do it with a group of students—it was a steep learning curve!

But the students learned how to approach the Center’s collections with their own queer sensibility—looking for traces in the collections of those who might not be well known, and attending to the ephemeral documents, notes in the margins, scrapbooks, diaries, letters, and personal photographs that can be guides to intimate lives behind the scenes. From there, we had to make tough choices about what to include in the exhibition, especially with our conceptually driven and capacious focus on queer intimacies and networks, and then design the layout and write the labels within a very short time.

In the end, the wide variety of objects tell many stories.

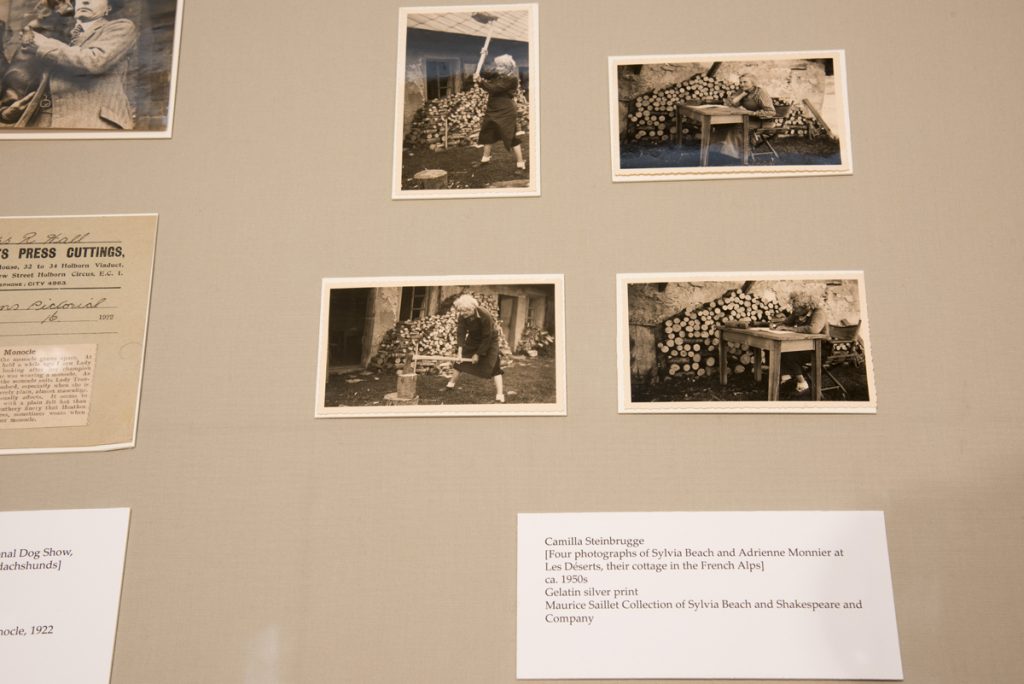

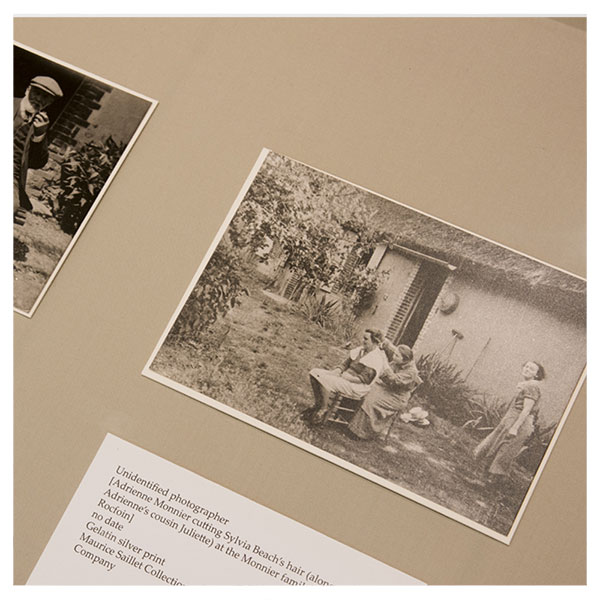

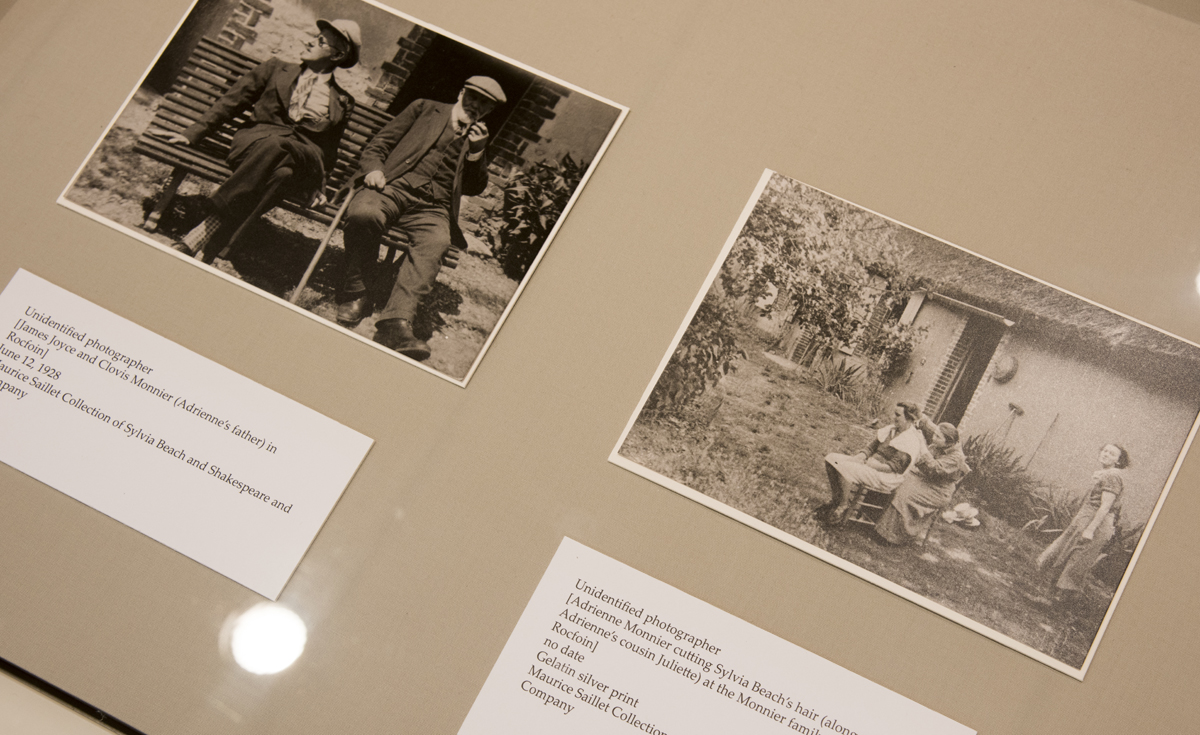

Sylvia Beach and Adrienne Monnier were the proprietors of Paris’s Shakespeare and Company bookstore and helped facilitate the publication of James Joyce’s Ulysses. To see Monnier tenderly cutting Beach’s hair at her family’s home outside of Paris or Beach chopping wood and posing at her desk at their cottage in the French Alps is to see the long-term relationship that helped sustain that more public work. These photographs added context to the Ulysses materials that were part of an earlier iteration of Stories to Tell in which Beach appears in a photo holding Joyce’s manuscript and is thus more of a handmaiden to him rather than someone with her own narrative.

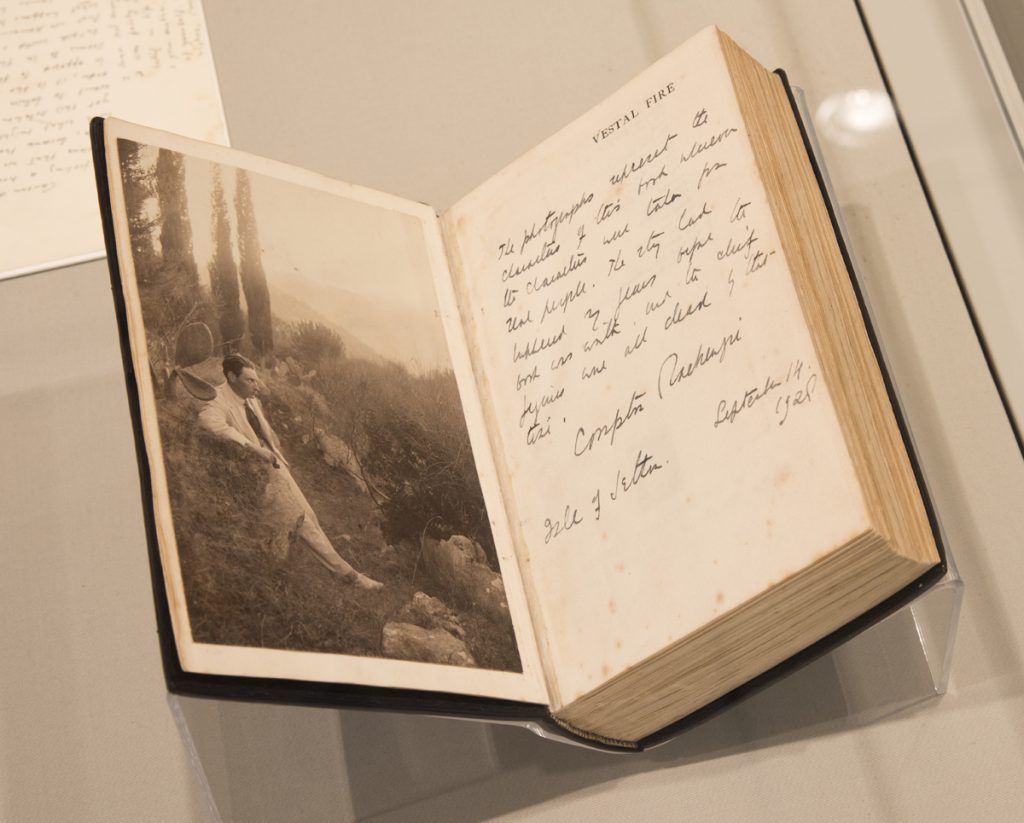

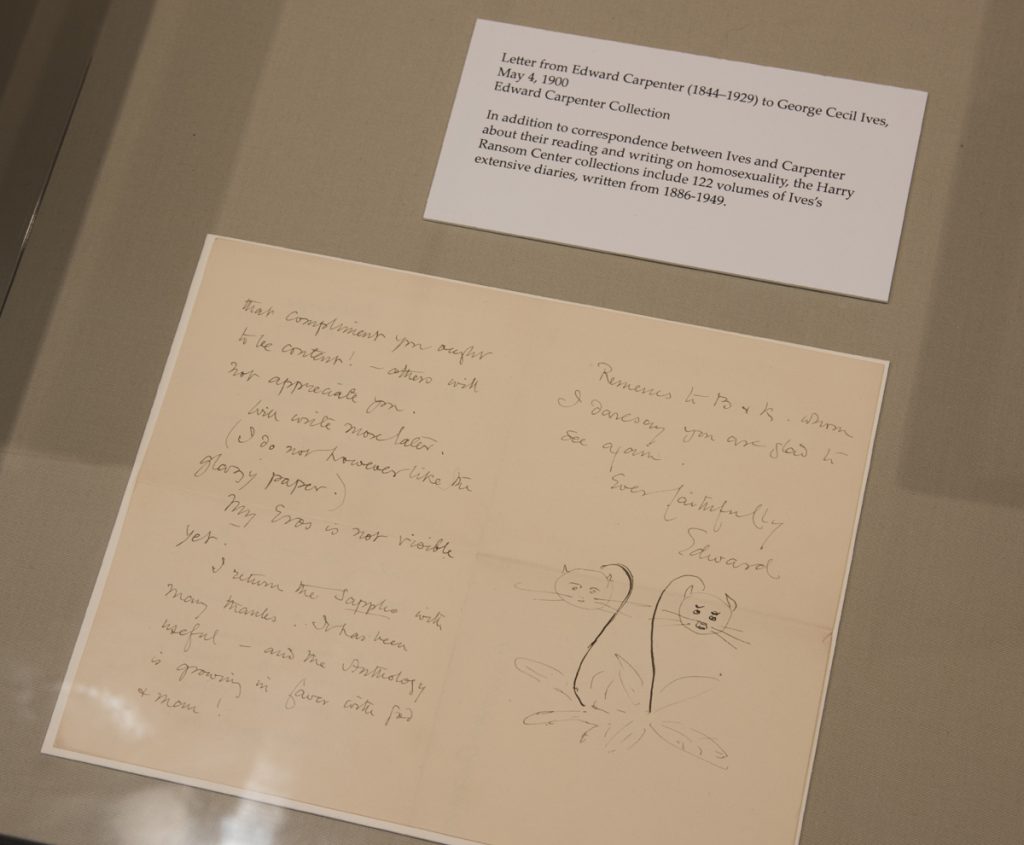

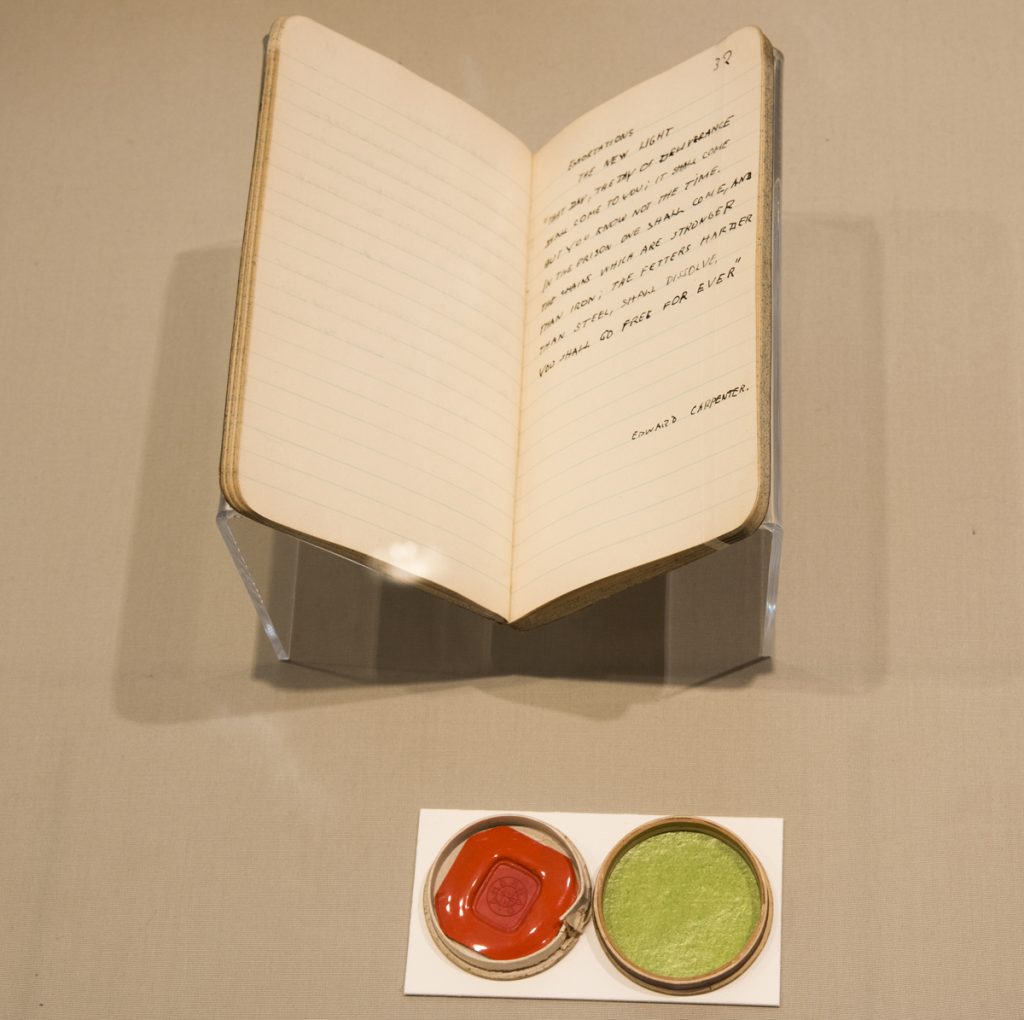

Examples of intimate correspondence include a letter to Carson McCullers from her friend Annemarie Schwarzenbach, whose dramatic life deserves its own archive. We included Sybille Bedford’s editorial notes from her former lover Evelyn Gendel, and Compton Mackenzie’s Vestal Fire, a roman a clef about gay and lesbian life in Capri. And we displayed an exchange between early homophile advocates Edward Carpenter and George Cecil Ives, whose diaries (all 122 volumes!) warrant greater exposure.

Of particular value for queer scholarship are the Center’s many collections related to the social circles around Charles Henri Ford, such as his sister Ruth Ford, Parker Tyler, and Pavel Tchelitchew. We included Tchelitchew notes to Gertrude Stein as well as his connections to the photographer George Platt Lynes.

The final image documents an exhibition of Lynes’s photographs that featured portraits of Gertrude Stein, Ruth Ford, George Balanchine, and Gloria Swanson, among others.

My hope is that this effort will lead to other ways of “bringing out” the Center’s collections. Figures that at first glance seem minor may actually hold queer connections and access to important histories.