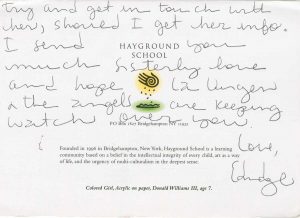

Image: Notecard card from Edgwidge Danticat to JuliaAlvarez; the image is titled Colored Girl.

In 1999, five years after Julia Alvarez’s In the Time of the Butterflies was published, the United Nations General Assembly cited the novel as an important cultural text that helped to pass the resolution to designate November 25 an official International Day of Observance for the Elimination of Violence Against Women. The date commemorates the November 25, 1960 assassination of the Mirabal sisters in the Dominican Republic under the brutal regime of Rafael Leonidas Trujillo (1930–1961).

Letters in the Alvarez archive revealed that Edwidge Danticat’s novel, The Farming of Bones (1998), which also tells of the violence committed by the Trujillo regime, was receiving a different kind of international political recognition. Danticat’s novel, a work of historical fiction, is a revisionist history of the 1937 “Parsley Massacre” (as it is called) in which an estimated 10,000 to 30,000 Haitians were killed on orders from Trujillo, an event that had long been under erasure.

The Farming of Bones critiques the Dominican people for turning a blind eye to the ethnic violence of 1937. Correspondence between Danticat and embassy officials from the Dominican Republic, who disavowed the massacre and took umbrage with her portrayal of Dominican complicity in the state-sanctioned mass murder, is documented in Alvarez’s archive. Alvarez became involved in this political dispute over the historical record because Danticat made public the support she received from Alvarez when she thanked her for being “so generous with time and directions” in the book’s acknowledgements. Edwidge Danticat wrote to Alvarez, “I feel I should apologize if you got any flack for being thanked in my book. But also feel I should thank you again for showing me such kindness.” As a prominent Dominican, Alvarez’s support of the novel garnered the attention of representatives of the government of the Dominican Republic.

Even without the benefit of seeing Alvarez’s responses to Danticat—and possibly to the Dominican government—the exchange of letters between the two women signals their participation in a long history of transnational feminist solidarity expressed through letters, such as Gloria Anzaldúa’s “Letter to 3rd World Women Writers” in 1980 in which she warned “not to capitulate to a definition of feminism that still renders most of us invisible.” The fact that Danticat and Alvarez wrote letters to one another and often crossed national and artistic borders together to fight against oppression, such as they did (along with Junot Diaz) in a October 29, 2013, editorial in The New York Times revealed to me the depth and complexity of their friendship.

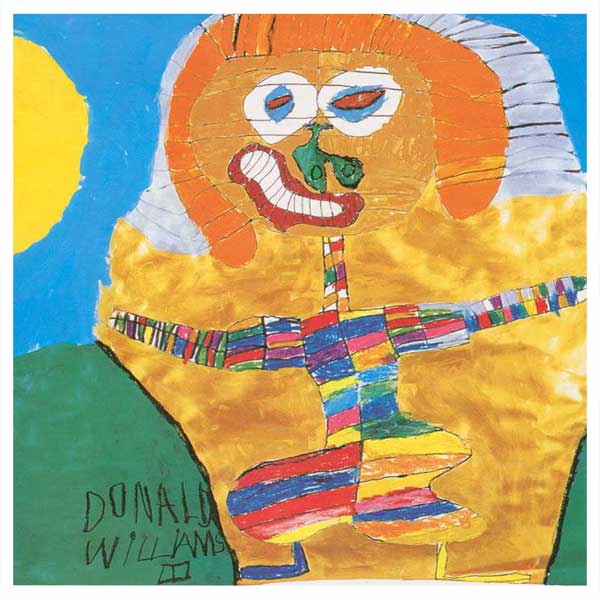

The card that Danticat sent to Alvarez is itself interesting. The image, titled “Colored Girl,” was painted by a 7-year-old and the vibrant colors and the girl’s proximity to the sun speak to the card’s description of “the urgency of multi-culturalism in the deepest sense.” The note written inside extends “sisterly love” to Alvarez, which can be read as an expression of a deep multiculturalism that their shared literary community makes possible. Through their popular and personal writings, Danticat and Alvarez risk crossing political, cultural, and historical borders that divide Dominican, Haitian, and U.S. communities. In the Alvarez papers, Danticat’s letters reveal a transnational feminist sisterhood that emboldens a community of writers to speak truth to power.

Sarah Papazoglakis is Ph.D. candidate and instructor in the literature department at University of California Santa Cruz. Her fellowship at the Ransom Center was supported by a dissertation fellowship, jointly sponsored by the Harry Ransom Center and The University of Texas at Austin Office of Graduate Studies.