Decades after its publication, this fictional account of the assassination of John F. Kennedy in Dallas remains provocative.

The depth of knowledge and range of opinions that can emerge from a good book discussion has always been one of my favorite aspects of reading. Even though it’s a solitary activity, it brings people together and gives us a common language. Questions (usually unanswerable) often emerge during book discussions about the intentions of an author. How fortunate then, to have access to the archives here at the Ransom Center where the creative process and choices made by an author can be gleaned from the materials in their archives. For our member book clubs, materials from a particular book are pulled from the archive and shown preceeding a discussion with small groups who have already read the work.

Using the archives to understand an author’s viewpoint is helpful, but clarity on the author’s every intention cannot be expected. I ask members in the discussion to think skeptically about what’s there, but also what’s not there. What might they wish was there (possibly a diary, a calendar, or a map that proves the author visited a particular setting)? Do those items reside somewhere else, or maybe they never existed? Conceivably, items have been lost over time. Just because it’s not in the archive doesn’t mean that it didn’t happen.

One book we recently discussed was Don DeLillo’s Libra, which has a thirtieth anniversary this year. The book is a fictional interpretation of the motives and events around Lee Harvey Oswald’s assassination of John F. Kennedy.

We examined archival items such as:

- A copy of the 26-volume Warren Commission report. DeLillo’s field research from walking around locations mentioned in the novel (New Orleans, Miami, Dallas) and keeping notes for each setting in a separate, small colorful notebook.

- A copy of a letter that Lee Harvey Oswald wrote when he was 16 years old to the Communist Party Youth League, asking if he could join.

- A copy of the Marine training manual from the era of Oswald’s enlistment. DeLillo underlined passages about weaponry and readers can see those lines reprinted in Libra.

- Reviews that DeLillo saved. Some positive, some negative. DeLillo occasionally reacted to the reviews and wrote notes and annotations directly on the printed articles.

The larger discussion focused on aspects of the book including the many characters and settings, and debating what parts were true and what might have been fictionalized.

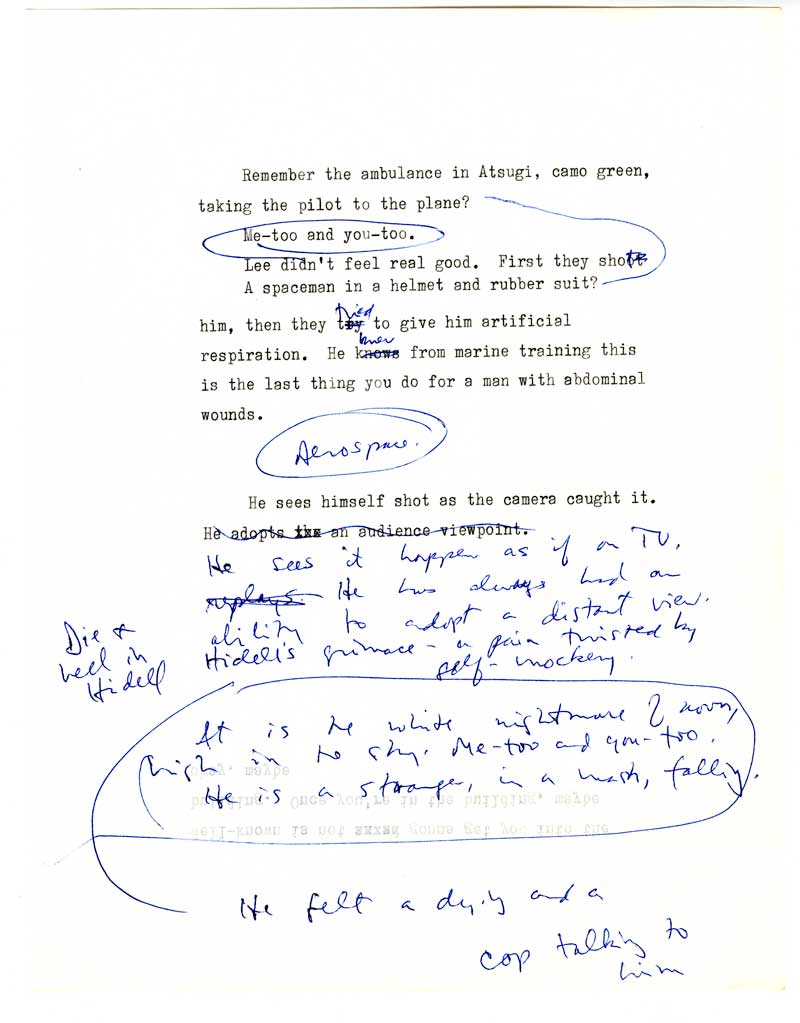

One thing I like to do when I’m selecting items from the archive is to show the author’s process by laying multiple drafts of the same passage side by side, so we can see how one scene builds and changes over time. DeLillo’s archive is particularly rich for this activity as he would re-work the same scene again and again until it met his standards. Each round of edits is laid out on a different typed page with annotations added by hand in pencil and ink.

We looked at three versions of the scene in Libra where conspirator Wayne Elko is in a movie theater following JFK’s assassination. We carefully examined what was rewritten and what details changed. Between each draft the number of people in the movie theater changed dramatically. We discussed why this might be. How did that change affect our understanding of the scene, or the larger book? The details about the particular films playing in the theater was also discussed, and the archive revealed a printed film synopses that DeLillo used as a resource for this scene.

Another item that prompted a lively discussion was a list DeLillo wrote to his publisher’s lawyers to tell them who the “real” and the “invented” characters were. Those were his words for it. The members found this added context to be invaluable because his characters were so believable as you read the novel it was not immediately obvious who the invented characters were. Our discussion of Libra repeatedly questioned which parts of the story were historical and which were fiction.

DeLillo’s archive helped guide us through his research and showed how he was able to accurately portray some of the historical facts, while being mindful about filling in gaps in the story with fictional aspects.