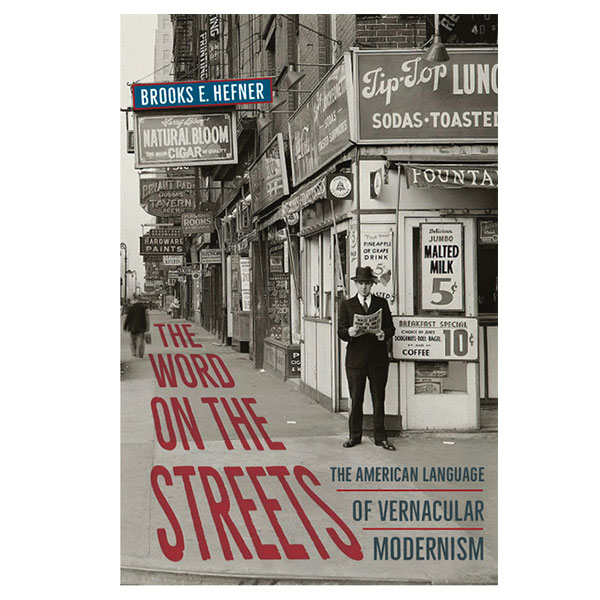

During the modernist era, writers experimented with the language of the street in their works. Brooks Hefner’s The Word on the Streets explores how multiple writers of different genres used street slang to emphasize classism through dialect. At the Ransom Center, Hefner consulted the archives of influential detective fiction writers Dashiell Hammett and Erle Stanley Gardner to inform his book.

Jared Neuharth: Why do the Hammett and Gardner collections represent “the most important archive of early twentieth century detective fiction in the United States?”

Brooks Hefner: There is simply not a lot of archival material on Dashiell Hammett held in public collections; the Ransom Center’s collection features correspondence and unpublished fiction from Hammett’s career. It’s an amazing look inside the working life of a writer who helped to revolutionize the model of the detective story. The Gardner collection is overwhelming; it features material not only related to Gardner’s creation of Perry Mason, one of the most popular fictional detectives of the twentieth century (adapted into television and film), but it also includes extensive correspondence with detective fiction magazines in which Gardner got his start. This is the only significant correspondence of this kind that has survived in archives and it gives a window into editorial attitudes and practices as new kinds of detective fiction began to develop. Gardner’s collection also includes drafts and research for Gardner’s “Court of Last Resort,” a true crime column-turned-television-show that was one the earliest cross-media examples of true crime writing and reporting.

Could you explain Hammett’s “objective style” of writing?

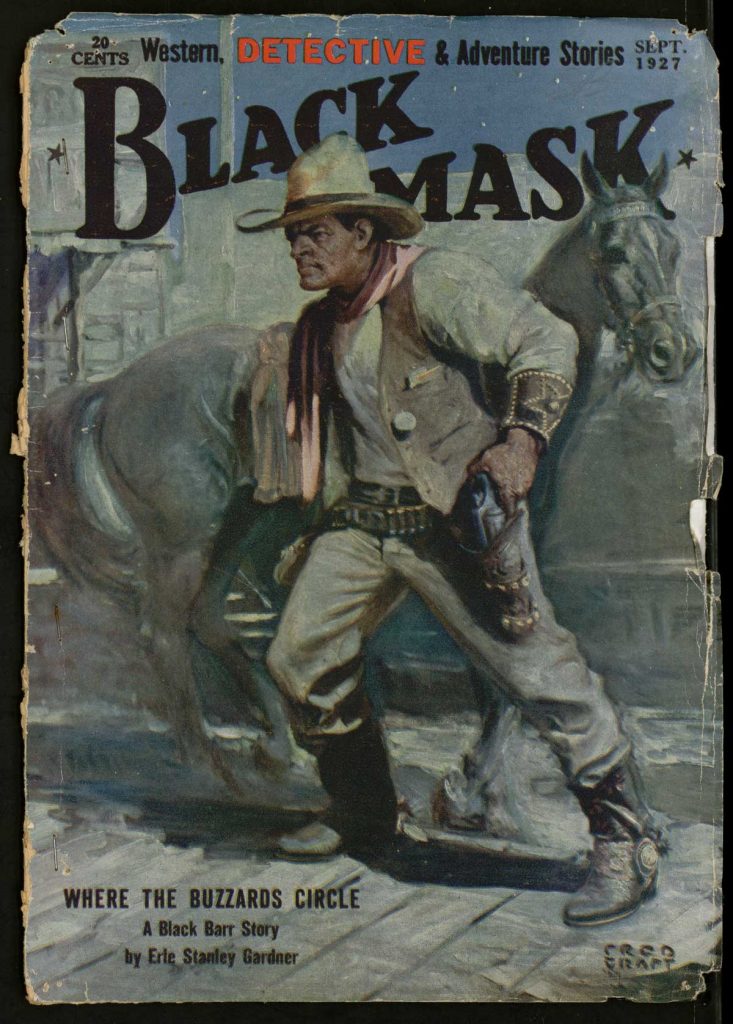

Hammett’s “objective style” (a phrase used by others, but not by him as far as I know) was hard, emotionless, and brutal. Rather than drawing the reader in by creating sympathy or identification with characters, it kept characters’ thoughts and feelings away from the reader. This is most evident in The Maltese Falcon, and it was deeply influential on the magazine Black Mask, where both Hammett and Gardner published regularly in the 1920s and 1930s.

Why did Hammett describe his work for pulp magazines as blackmasking?

This was Hammett’s joke. He began his career wanting to write “serious” fiction and published a few short pieces in The Smart Set, then one of the more interesting literary journals in the U.S. (F. Scott Fitzgerald published there). When he couldn’t continue his success, it’s likely that an editor therewho had a stake in the pulp magazine Black Mask—suggested he try his luck in that pulp. So he used “blackmasking” as a way to describe writing for these pulp magazines, producing work of (he thought) lower literary quality. It’s almost the equivalent of “selling out.”

Did you make any surprising discoveries while researching in the Ransom Center’s Hammett and Gardner collections?

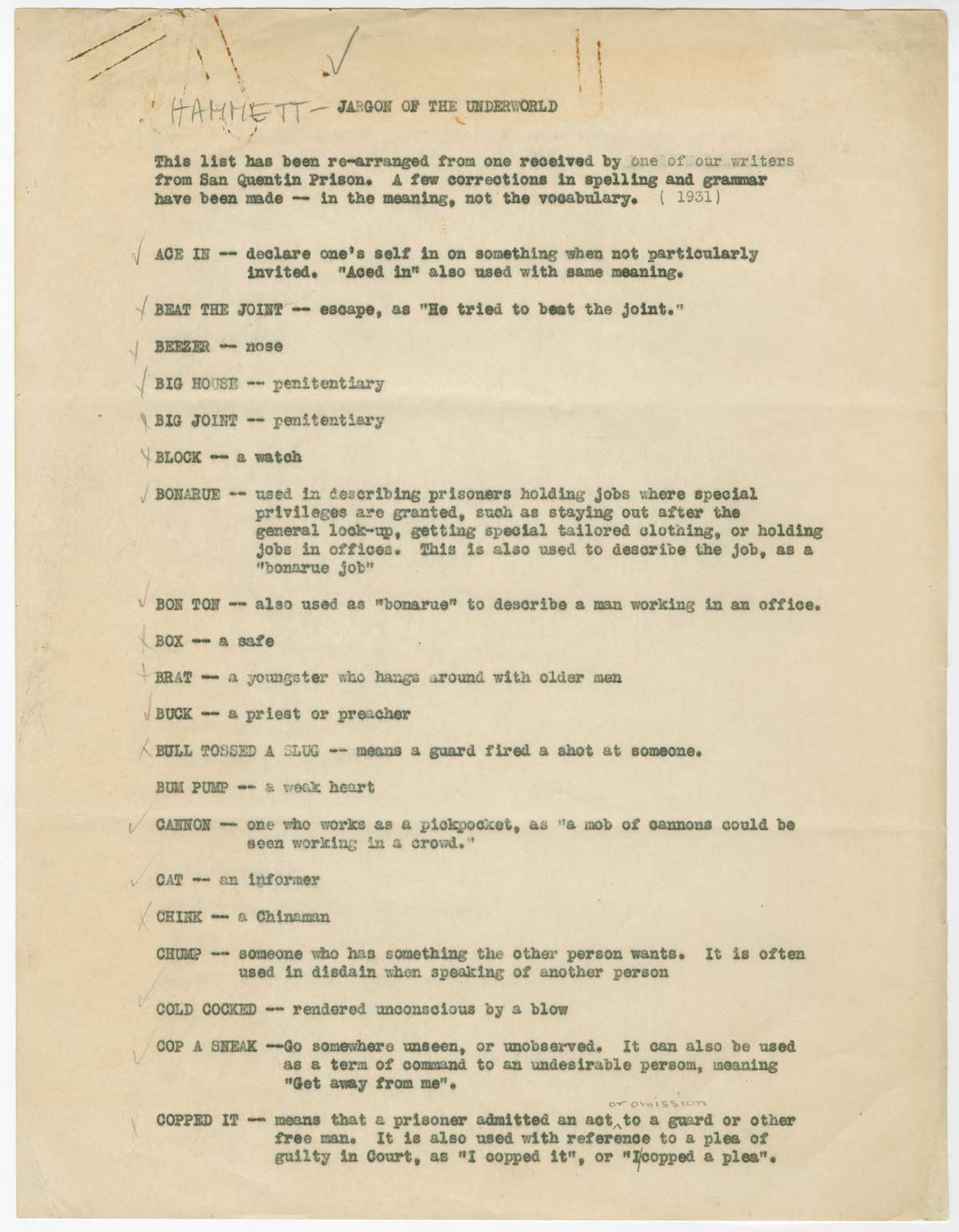

One discovery that was very helpful for my book was a collection of underworld slang that was in the Hammett papers. It’s a little unclear what it was for, but it seems like something Hammett may have been trying to publish in the early 1930s. The Gardner collection included, as I mentioned above, extensive correspondence with magazine editors, and much of this correspondence (especially the letters from editors) paints a rich picture of the history of each magazine. I spent most of my time with his correspondence with Black Mask, and this offers a very detailed look at how the magazine sought to keep popular writers in the face of competition from new magazines, how it dealt with the financial difficulties in the Great Depression, and how the personalities and goals of editors and writers could diverge with significant consequences.

The Gardner collection, as you put it, could occupy a scholar’s entire career. How did you find what you needed?

The librarians at the Ransom Center were very helpful on this account. There is a print finding aid (there was no digital one when I was there), and the collection is well organized, so I was able to target key correspondents (specific magazines like Black Mask and other writers with whom Gardner had a relationship). A lawyer by training, Gardner kept track of everything. There was also some dumb luck involved. I could have easily waded through his correspondence with other competing magazines and publishers, but there was only so much time when I was there!

Do you prefer Hammett’s or Gardner’s writings?

Hammett is one of my favorite writers, period, so I’d have to go with him here, but he didn’t produce a lot of fiction (you could read it all in a few weeks). The nice thing with Gardner is that he wrote so much—on top of the mountains of correspondence in the collection at the Ransom Center—it’s not hard to come across a mystery novel of his that you haven’t read. So, while Hammett calls for re-reading (I’m a big fan of Red Harvest, which I teach regularly), Gardner’s novels seem to go on forever, so you’ll always have something new with him.

Brooks Hefner was the recipient of a Harry Ransom Center research fellowship supported by the Erle Stanley Gardner Endowment for Mystery Studies.