Walt Whitman was born on this day in 1819, and amid a panoply of planned festivities, his bicentennial has renewed popular interest in Whitman’s legacy. What has Whitman left us in our twenty-first century? Whatever he has bequeathed to us culturally, what’s certain is that 200 years after his birth, his textual legacy continues to grow.

In the first place, he’s left us whole volumes of prose we never knew existed until recently, landing him on the front page of the New York Times twice in as many years: in 2016, with the discovery of his men’s fitness column, and in 2017 with the discovery of his lost novel, The Life and Adventures of Jack Engle. That these works eluded scholars for more than a century testifies to the staggering velocity with which Whitman produced written words during his lifetime, as he amassed a formidable corpus of documents. The Harry Ransom Center alone holds more than 400 such documents, a sizable collection in itself but dwarfed by the tens of thousands of written works by Whitman held at the Library of Congress, for instance, more of which each year are being digitized and added to the online Walt Whitman Archive.

“Boundless” might be an apt descriptor. It’s one Betsy Erkkila and Jay Grossman center in their collection of essays, Breaking Bounds, about Whitman the cultural boundary-crosser. And it’s one Whitman himself used frequently in Leaves of Grass to describe the “boundless vista” and “boundless blue” of the sea, the “boundless expectant soul” of a mother, and the “boundless summer growths” from the “brown parturient earth.” “O to realize space!” he writes, “The plenteousness of all, that there are no bounds,” famously claiming elsewhere that “All goes onward and outward”—“Nature without check.”

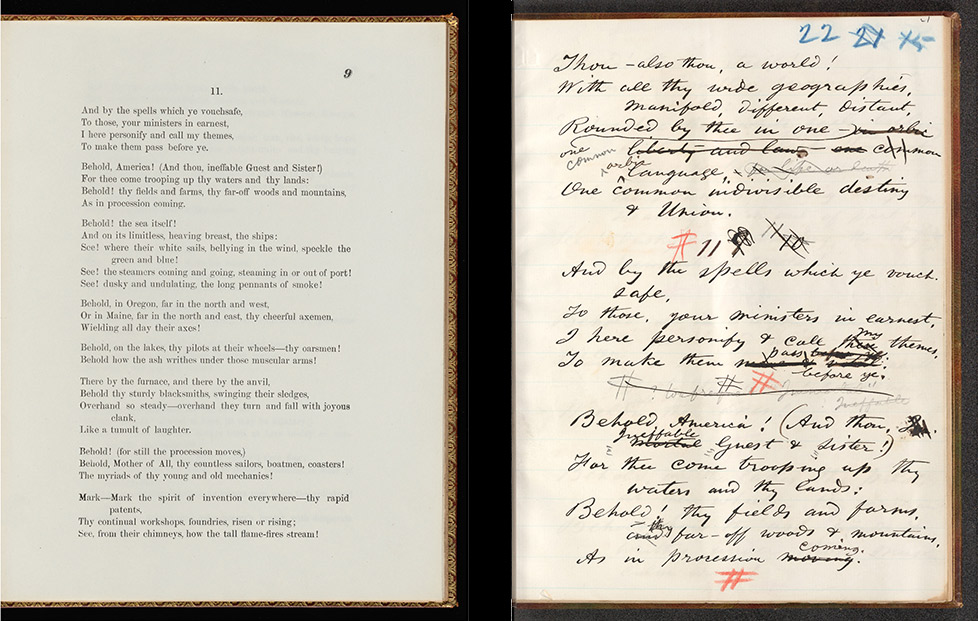

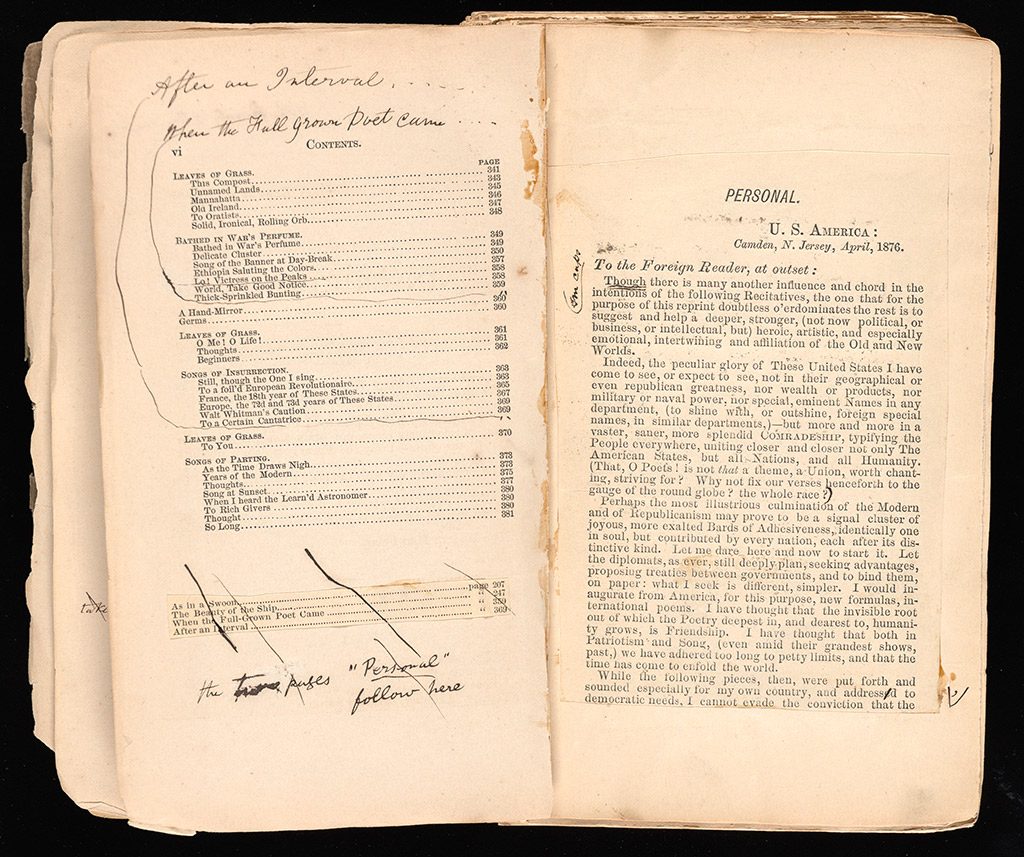

Of course these lines are, after all, bound. Whitman’s more literal Leaves of Grass, playing on the word “leaf” to mean “page,” grew in ways “onward and outward” as grass does, in so far as Whitman expanded his volume during his lifetime from 95 pages in his first edition to 438 in his last. From 1855 to 1892, his Leaves of Grass multiplied fourfold! Nevertheless Whitman was insistent on and attentive to the bindings of his Leaves of Grass, and sometimes other leaves besides. Whitman wrote that he contained multitudes: most readers have focused on the multitudes, but attention should also be paid to the fact that he endeavors to contain them.

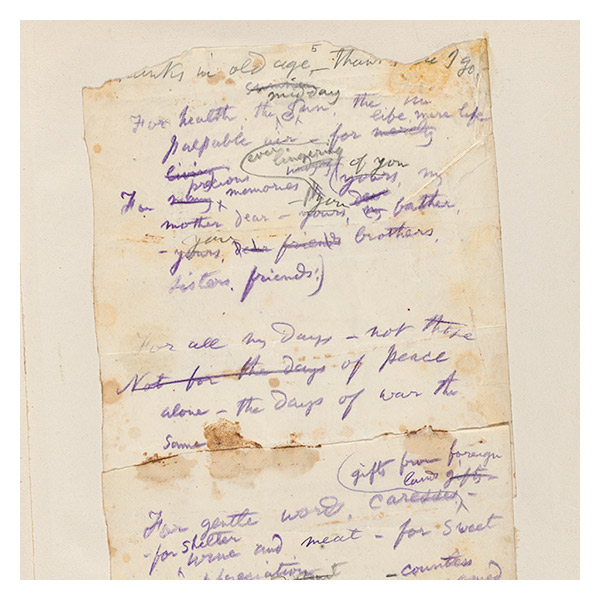

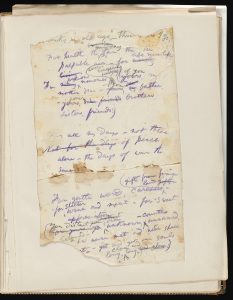

In returning to the question of what Whitman has left us upon his bicentennial, we might turn to Whitman’s own answer. In his poem, “My Legacy,” part of his “Songs of Parting” placed toward the end of his deathbed edition of Leaves in 1892, Whitman writes that though the “business man […] Leaves money to certain companions to buy tokens, souvenirs of gems and gold[,]” Whitman leaves no such estate:

Yet certain remembrances of the war for you, and after you,

And little souvenirs of camps and soldiers, with my love,

I bind together and bequeath in this bundle of songs.

What is Whitman’s legacy? According to him, “this bundle of songs” he has bound together. As Ed Folsom writes in Whitman Making Books/Books Making Whitman, “Whitman is the only major American poet of the nineteenth century to have an intimate association with the art of bookmaking.” He is known as, to quote Nicole Gray, “a controlling force in the making of his books, involved at every point in the process, from design to printing, binding, and distribution.”

To Whitman, bookmaking was a social act. He thought not only of “This printed and bound book—but [also] the printer and the printing-office boy,” and he had personal preferences for which printers and binders to work with. Toward the end of his life, he worked frequently with Frederick Oldach, a German binder out of Philadelphia whose “absolute knowledge of binding” Whitman described in the binder’s native tongue as “meisterschaft,” or mastery.

As to the bindings themselves, Whitman’s preferences tended toward strength and utility over ornament, and he disdained “disciples of finesse—advocates of taste, laces, bindings, ornamentation—protagonists of filigree: tailor-men,” whom he associated with aristocracy, even as that aristocracy asked him for finer bindings of his own work: “there are places, people, who want them: the big British libraries, the museums: even here there are some rich men: rich men’s sons, families.” But Whitman was “an American, one of the roughs,” and so his volumes must reflect this:

I have no sympathy whatever with handsome books (handsome whether or no), showy appearances, unique styles, costly dressings, merely for themselves. I never had any desire to set myself apart—to claim special privileges, exceptional attentions. […] My wish has been to merge myself with the masses, be a drop in the ocean, mingle with the bulk: I have not sought, do not seek, any distinction—any rare exaltation.

At another time:

Binding illustrates all life. Show a man a house—one that may be plain but in and out everything that is honest, durable: he shakes his head: is there not something more? So you show him a reverse case—show, ornament, external bother: he at once applauds!

And another:

The book must be substantial, rich, without making a show, a glitter: rich not after the binder’s fashion or the booksellers’, but on other rules, manners—ours.

Whitman’s books would not be so ornamental, at least not merely. Moreover, they would not be inaccessible. Whitman often eschewed more expensive bindings in favor of making his volumes more affordable to “the masses.” Then again, he disliked cutting corners, telling his young friend Horace Traubel, “we’ll make our book right even if it costs every cent.” And more than occasionally, especially for commemorative editions, he’d splurge.

When Traubel revealed to Whitman the copies of his 1889 November Boughs, the printing that to date was Whitman’s favorite second only to the 1855 edition of Leaves, Whitman’s eyes grew “large with desire.” “[T]hat is the book—the real, living, undoubted book!” he exclaimed, continuing: “My blood, your blood, went to the making of this book! Some men go to the North Pole to do things—some go to wars—some trade and swindle: we just stayed where we were and made a book!”

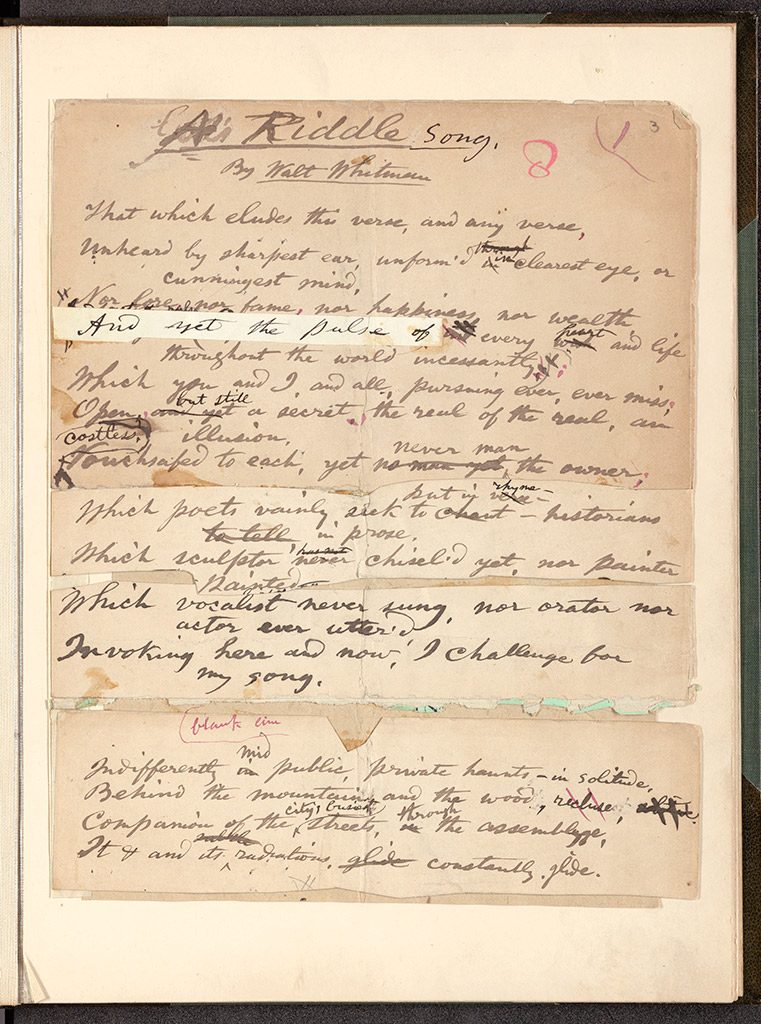

In keeping with Whitman’s rapture about “the way books are made,” and his interest in making them widely accessible, the Harry Ransom Center has digitized 10 bound volumes of Whitman’s work from our holdings. Among the works featured are a bound copy of Whitman’s original notes for his lecture on the death of Abraham Lincoln that Whitman sent to Bram Stoker; manuscripts and proofs for editions of A Riddle Song and After All, Not to Create Only; proofs for London editions of Two Rivulets and Leaves of Grass; manuscripts and notes for his “Sunday Evening Lectures” on Kant, Fichte, Schelling, and Hegel; and more.