Most of the books that came to The University of Texas at Austin as part of the John Henry Wrenn Library didn’t look like old books when they arrived in 1918 and still don’t look old now—not as old, at least, as the publication dates of the printed pages inside would suggest.

The earliest volumes date from the 1500s, and their bindings feature dyed goatskin leather of the highest quality, with shiny gold lettering, decoration, and page edges. Open their covers and you’ll see marbled endpapers, too, and even more gold decoration. Most of this high-end work was done around the turn of the twentieth century by the London bindery of Rivière and Son, which served elite book collectors on both sides of the Atlantic. And old books handled by the firm often have secrets to tell.

The artisans at Rivière and Son were not only skilled binders but also experts at repairing paper. They could take damaged leaves from early printed books and fill losses with other paper without creating a visible seam. They were even able to match the chain and wireline patterns present in early mold-made paper. They were also able to remove the dirt and stains that had accumulated over the centuries by washing leaves and then flattening and compressing them in a press. In the case of many books in the Wrenn Library, a combination of repair, washing, and pressing made it possible to make leaves originally from different copies appear uniform when brought together between a single pair of covers. I discussed these books—some of which include leaves stolen from the British Museum by a man named Thomas J. Wise—as part of a recent Stories to Tell exhibition at the Center and in its accompanying publication, Collated & Perfect. Other Wrenn books in Rivière and Son bindings aren’t “Frankenstein” copies, but they have usually been washed and pressed and include some paper repairs.

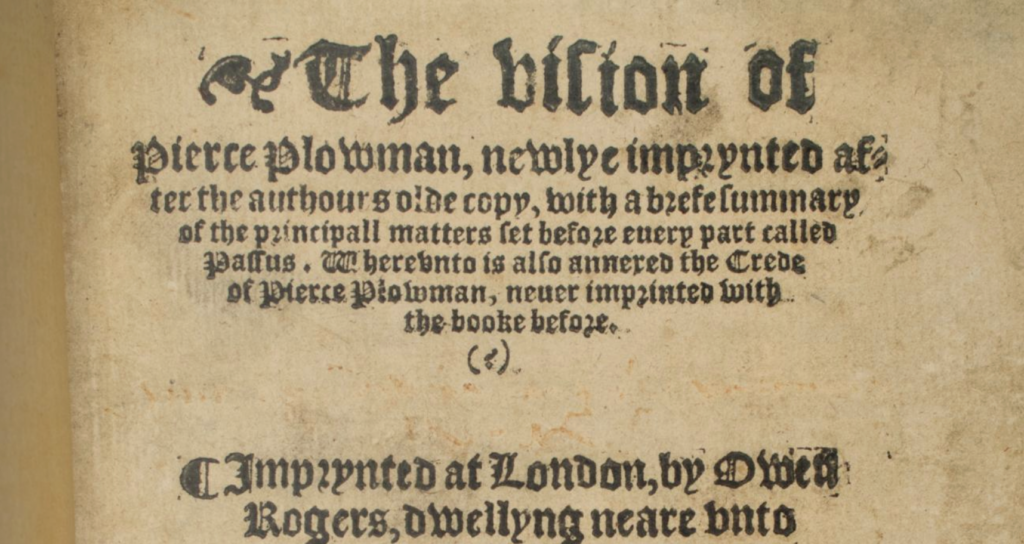

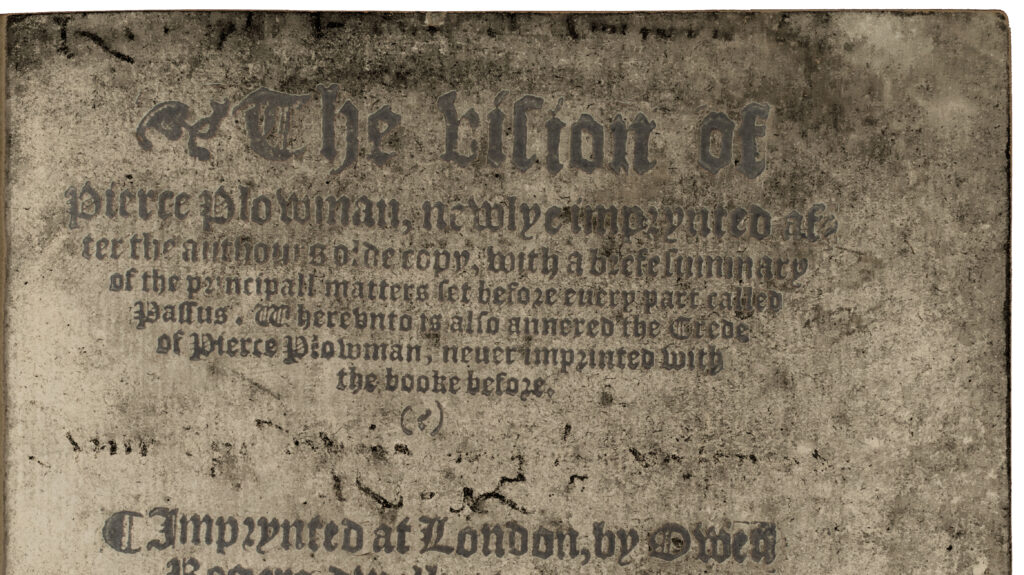

A couple of months ago, a reference question from a UT faculty member took me into the stacks to retrieve Wrenn’s 1561 edition of Piers Plowman, a poem written by William Langland toward the end of the fourteenth century. From the texture of the paper alone I could tell that it had been treated. As part of the book’s original binding process in the sixteenth century, the paper would have been beaten and pressed, but the pages of books that remain in early bindings retain some of the original texture of their handmade paper; it is often possible, too, to see and feel impressions where the metal type was in contact with the paper during printing. Not so in this book, where page surfaces are so smooth that they feel almost like cigarette paper. Such clear signs of modern washing and pressing always put me on alert.

With washing and pressing comes increased risk of a copy’s leaves being from multiple sources, and washing and pressing doesn’t only remove dirt, it can—and often was intended to—wash away inscriptions by early readers. In the Plowman copy, the title-page is a beige or tan color, with some irregularities here and there, especially near the edges. This is fairly typical, but because the smooth texture made me more attentive, I noticed orange marks in a blank area just above the imprint. Upon examination, it was clear that these were traces of early handwriting, but it was difficult to make out the words. Fortunately, a high-resolution camera and Photoshop made it possible to increase the contrast selectively, giving me a clear view of a couple of words: “divina,” “nihil,” and a word starting with “v” and ending with “emus.” I could also see the initials “R. K.” underneath. I posted some photos on Twitter with a call for help deciphering the inscription, and scholar Mari-Liisa Varila offered an answer: “Sine ope divina nihil valemus,” which means “Without God’s power we can accomplish nothing.”

Incredibly, a Google search for the Latin returned a link to a digitized copy of Book-Prices Current, which included a description from Sotheby’s of the very same copy that is now in the Wrenn Library—but before Rivière and Son had scrubbed and rebound it. In 1897, when Sotheby’s auctioned the book in London as part of the famous Ashburnham Library, it was still in a binding of “old calf.” In addition to confirming Dr. Varila’s reading, the description provided exciting new information: there is—or was—another inscription at the top of the page: “Ranulphi Kent et Amicorum Liber,” “Ranulph Kent and [his] friends’ book.” When Wrenn bought this Piers Plowman at a New York auction in 1900, the catalog description made no mention of any inscriptions but noted that the book was bound in “full crushed levant morocco extra, [with] gilt edges, by Rivière.”

The Ranulph (or Ralph or Randle) Kent who inscribed the volume was in all likelihood the headmaster of the grammar school in Nantwich from its founding in 1572 until shortly before his death in January 1624. Conveniently, images of his will are available from the Cheshire Archives for a small fee. Atypically, the probate inventory of Kent’s personal property is preserved with it. In total, his belongings were assessed at a little under £47.50. He had kept 27 books, along with a few others, “In the studie,” and the inventory specifies these were “geven to the Schoole.” Together, Kent’s books were valued at £20, or more than 40% of the inventory’s total. It is unclear whether his Piers Plowman was among these books when assessed or if it, perhaps, had already made its way into the hands of a friend. What is clear is that Ranulph Kent was a man committed to books. He read, and he wanted his friends and students to benefit from reading, too. Especially provocative is the possibility that he might even have considered Piers Plowman an edifying enough poem to teach it to schoolchildren.

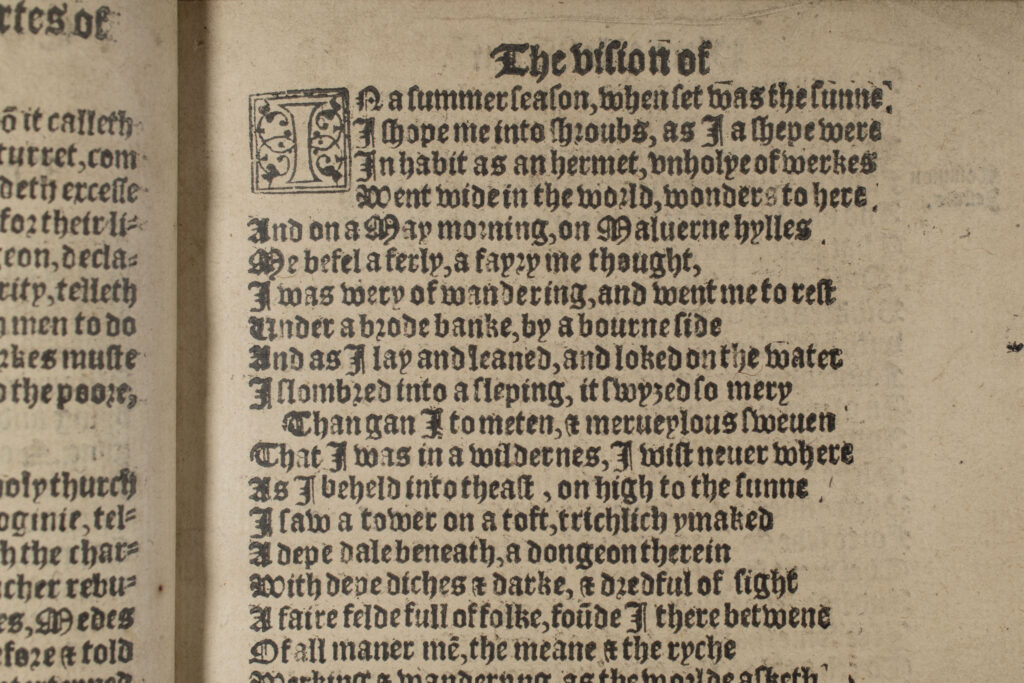

Originally written in Middle English in alliterative verse during the fourteenth century, Piers Plowman is long and complex. At the most basic level, it tells of a man named Will who has a series of dream visions that track his spiritual journey as a Christian while offering what is often biting religious and social critique. The title character, Piers Plowman, appears throughout the visions as both a literal plowman and a Christ figure. In its time, Piers Plowman was well known: a substantial number of manuscripts of the poem still survive, and leaders of the Peasants’ Revolt in 1381 referred to the poem and its characters in a speech and in writing. Almost 200 years later, in the sixteenth century, Protestant reformers adopted Piers Plowman as an ally, too. Indeed, by the time Ranulph Kent owned his copy, Piers Plowman would have been understood by many readers as a proto-Protestant poem.