In 1934, publicist Reeves Lewenthal called together a group of 23 American artists to discuss his innovative plan for distributing art to the American public. Lewenthal proposed producing signed fine-art prints in editions of 250 and selling them directly to the customer, a move that would bypass the established elite gallery system and reach a larger middle-class audience. Encouraged by the prospect of a steady income during the Great Depression, a number of artists signed on, and from Lewenthal’s idea New York–based Associated American Artists (AAA) was born.

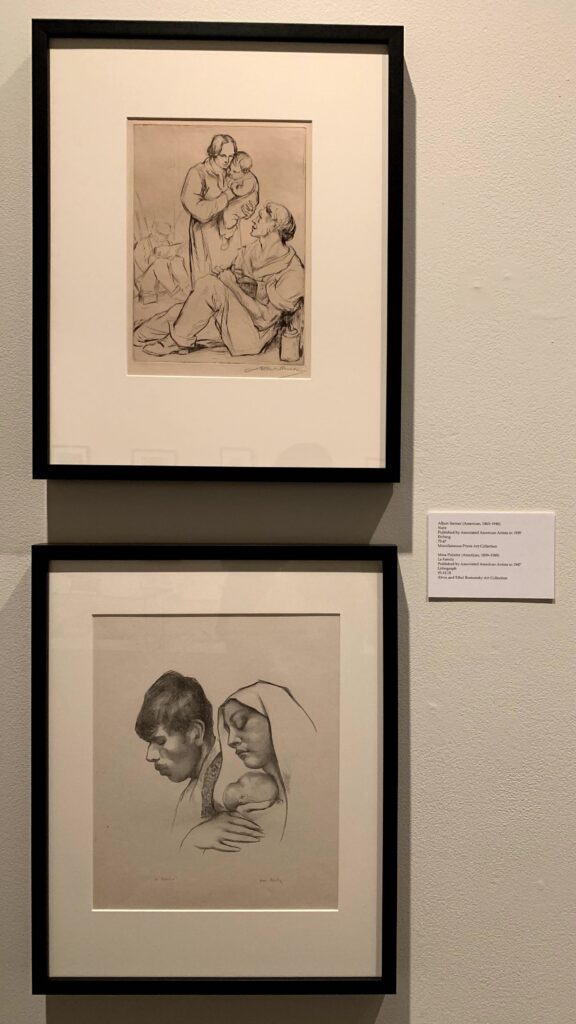

Lower: Mina Pulsifer (American, 1899–1989), La Familia, 1947, Lithograph. Alvin and Ethel Romansky Art Collection, 93.10.18.

Improbably launched at a time when most American households had little income to spare, AAA first sold its prints through department stores, and, beginning in 1935, via mail-order catalogs. The company’s advertisements ran in such magazines as Life, Time, and Reader’s Digest throughout the 1940s, stoking interest in the chance to purchase original, signed, limited-edition prints at the price of $5 apiece (approximately $90 today). Some of the era’s best-known “American Scene” painters, including Thomas Hart Benton, John Steuart Curry, and Grant Wood, produced prints for AAA, and soon AAA prints were displayed in homes all over the country.

Part of Lewenthal’s early strategy to increase interest—and sales—included promoting a better understanding of printmaking techniques. Accordingly, AAA published such books as Understanding Prints: A Common Sense View of Art, by Aline Kistler (New York: AAA, 1936). These guides offered advice for assessing the formal qualities of a work of art and described various printmaking techniques. Many AAA artists created lithographs, but early in the twentieth century lithography was still largely associated with commercial production. Accordingly, AAA referred to all its prints as “etchings” until 1941, regardless of the actual technique used.

Lower left: Grant Wood (American, 1891–1942), March, 1941. Lithograph. Richard Gonzalez Collection of Associated American Artists Prints, 83.135.60.

Top Right: Adolf Dehn (American, 1895–1968), Key West Beach, 1947. Lithograph. Richard Gonzalez Collection of Associated American Artists Prints, 83.135.20a.

Lower right: Charles Wheeler Locke (American, 1899–1983), Waterfront. 1938. Lithograph. Richard Gonzalez Collection of Associated American Artists Prints, 83.135.36a.

When AAA was launched, social realism and regionalism were broadly popular art movements in the U.S., and profitable subject matter for AAA prints included portraiture and landscapes. Even as the larger European and American art world increasingly turned toward abstraction in the wake of World War II and the decades that followed, AAA largely rejected this movement. As many earlier WPA-FAP artists who produced social-activist works had found, there existed a stark contrast between what might make for a successful gallery or museum display and what middle-class Americans wished to see hanging on their walls.

This turn away from broader art-world movements was not entirely by design, however. AAA asked Abstract Expressionist artist Jackson Pollock to produce work for the company, but was refused. Lewenthal also contacted Pablo Picasso and Salvador Dali, both of whom expressed interest in working with AAA, but Thomas Hart Benton—who rejected European modernism and whose highly popular lithographs were reliable best-sellers—threatened to quit if those artists came on board.

AAA did achieve compelling international partnerships, however. An early example is the 1947 12-print suite entitled Mexican People, produced by 10 members of the Mexico City-based collective Taller de Gráfica Popular.

Collectors of AAA prints tended to purchase sizable numbers of the works over time—AAA regularly produced tempting catalogs of prints, and its advertising encouraged buyers to fill their homes with the purchased artworks and to frequently rotate what was displayed on their walls. The company also offered framing and home storage solutions to help make it feasible for the average American household to collect large numbers of artworks. As a result, museums and institutions like the Ransom Center frequently acquire entire personal or family collections of AAA prints rather than individual works. A look at any one collection can tell as much about the tastes, interests, and strategies of individual collectors as it does about AAA and its artists.

Top center: Joseph Hirsch (American, 1910–1981), Man and Beast, 1948. Lithograph. Richard Gonzalez Collection of Associated American Artists Prints, 83.135.30a.

Lower center: Peter Hurd (American, 1904–1984), The Sheep Herder, 1937. Lithograph. Richard Gonzalez Collection of Associated American Artists Prints, 83.135.33.

Right: Benton Spruance (American, 1904–1967), Dark Bed, 1962. Alivn and Ethel Romansky Art Collection, 88.80.354.

While many changes in the company took place after World War II, AAA successfully marketed prints—and, later, paintings as well as textiles, tableware, and other home furnishings designed by artists—until 2000.

The images above are taken from the Spring 2020 Stories to Tell installation For the Walls of America: Prints from Associated American Artists. Although the Ransom Center is currently closed to the public, these prints will be available to view in our galleries when we are able to reopen.