Lewis Allen was a respected theater and film producer. His biggest hits on stage were Annie (1983), I’m Not Rappaport (1985), A Few Good Men (1989), and Master Class (1995). His films include The Connection (1961), The Lord of the Flies (1963), and Fahrenheit 451 (1966). But, when Allen’s daughter Brooke donated her father’s archive to the Ransom Center in 2006, she told me that of all her father’s films, the one which he was most proud of was a 1968 documentary called The Queen. I took that to heart. For more than a decade, preserving the film and making it available has been a favorite project of mine.

In the years before the riots at the Stonewall Inn in New York City that many consider to be a turning point in the struggle for LGBT rights, life for gay Americans was difficult at best. The harassment and persecution of homosexuals went beyond anti-sodomy laws to include anti-gay hiring practices and local ordinances that restricted where and how gay people could gather. Those who differed from heteronormative gender expressions, including effeminate men, masculine women, and people who dressed in drag were especially vulnerable.

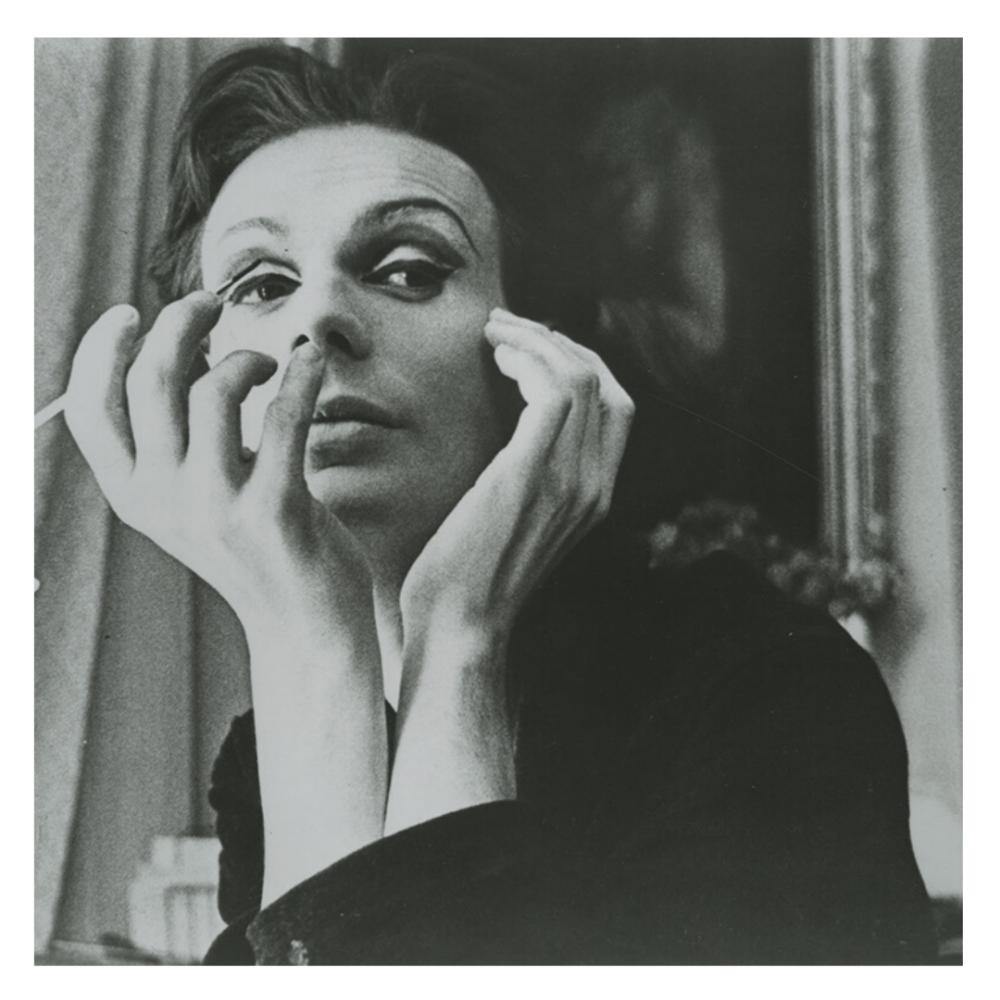

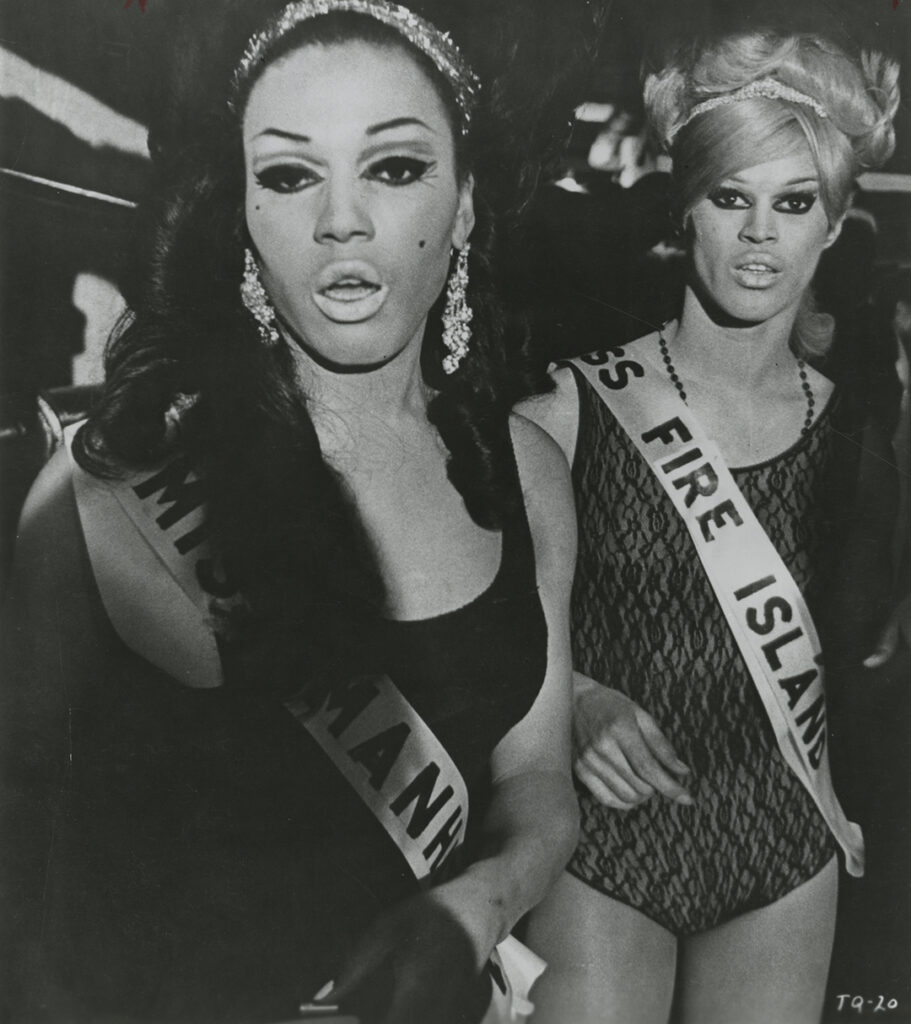

Jack Doroshow, whose drag name was Flawless Sabrina, sought to foster community at this time by organizing drag beauty contests and promoting them as charity fundraisers and entertainment for primarily gay audiences. Beginning in New York and eventually moving to other major cities, the drag pageants grew in popularity and in 1967, Flawless Sabrina organized the “The Miss All-American Camp Beauty Pageant,” which brought winners of the local pageants together to compete for the national crown. New York’s underground art community was closely connected to and supportive of the drag scene so Andy Warhol and Edie Sedgewick were the first to sign on as judges. Another artist, Sven Lukin, and cinematographer Frank Simon, approached entertainment lawyer Si Litvinoff with the idea of filming a documentary of the event. Litvinoff was enthusiastic and called his friend Terry Southern who in turn recruited the artist Larry Rivers and Bernard Giquel from Paris Match. Before long artist Jim Dine and writers George Plimpton and Rona Jaffe were involved. Most importantly, Litvinoff enlisted his friend Lewis Allen, a theater producer who had extensive experience and success with film projects including The Connection (1961), Lord of the Flies (1963), and Fahrenheit 451 (1966).

The film they made was titled The Queen. Grove Press, long known for publishing controversial material and fighting censorship, had started a film distribution arm and chose The Queen as its first title. Lewis Allen, Si Litvinoff, and their partner John Maxtone-Graham, went to work arranging screenings for reviewers and working with Grove to book dates in theaters. Many of the initial reviews were positive. In her review for New York Magazine, Judith Crist wrote, “…what might have been a grind-house or underground movie emerges as an impressive and perceptive human document and a finely made film as well.” Renata Adler wrote in The New York Times, “…these gentlemen in bras, diaphanous gowns, lipstick, hairfalls and huffs—discussing their husbands in the military in Japan, or describing their own problems with the draft—one grows fond of all of them.” Other reviews were negative, even brutal, in their dismissal of the contestants and the film. One uncredited review called The Queen a “beauty contest for the sick.” Another called it “pathetic and boring.”

As Grove and the film’s producers struggled to book the film in major cities in the United States and abroad, they ran into unexpected obstacles. The Los Angeles Times, for example, censored ads for The Queen, excluding images and editing text from the ads to eliminate any mention of the film’s

subject matter.

Every success, it seemed, was followed by another disappointment. The Queen was accepted into the 1968 Cannes Film Festival’s International Critics’ Week and was enthusiastically received. Truman Capote, one of the judges for the festival that year, told Litvinoff that the jury intended to give The Queen an award. But that was the year that the de Gaulle administration attempted to fire Henri Langlois, the founder and head of the Cinémathèque Française, the French film archive, which caused an uproar and united much of the French film industry in protest. Demonstrations against the government’s treatment of Langlois and the Cinémathèque developed into protests and confrontations between young people, mostly students, and the government and quickly expanded into nationwide strikes, occupations, and shutdowns. At the Cannes Film Festival, a group of filmmakers lead by Jean-Luc Goddard and François Truffaut sought to shut down the festival in solidarity with the nationwide strike. They succeeded and The Queen, which had caused a sensation at its screening before the festival’s closing, went home without an award.

The film played in a few cities in the US and in Great Britain, France, and Denmark where the producers had succeeded in negotiating a distribution agreement. But box office receipts were disappointing and The Queen drifted into obscurity until 1990 when Paris Is Burning, Jennie Livingston’s documentary was released. Paris Is Burning examined 1980s Harlem drag ball culture which had evolved from drag beauty pageants such as those depicted in The Queen. Furthermore, Paris Is Burning featured Pepper LaBeija, head of the “House of LaBeija,” which was founded by Crystal LaBeija, whose angry outburst over losing the competition is the climax of The Queen.

Allen and Litvinoff hoped to capitalize on the popularity of Paris is Burning by re-releasing The Queen in theaters and on the relatively new format of VHS “home video.” They arranged a screening at New York’s Film Forum to reintroduce the film to the public. Promoted as a benefit for the AIDS Initiative of The Actors Fund of America, the screening was a huge success. But the filmmakers’ plans were again thwarted. Exhibitors complained the film was too short to justify the ticket prices and the VHS release was buried in an avalanche of home video releases. The Queen again drifted into obscurity, and until now, was available only on the few copies of the VHS release still in circulation, black market DVDs, or on the single battered 35mm print owned by Litvinoff.

Since the Lewis Allen archive arrived at the Ransom Center in 2006, dozens of graduate students have rewound and rehoused the hundreds of unlabeled, under-labeled, and mislabeled “finger rolls” of film—from camera original footage to rough cuts and audio tracks—that made up the bulk of footage from The Queen. We created an inventory of these film rolls and combed through the archive to research the history of the production. This work in turn enabled our friends at UCLA’s Film and Television Archive to identify the specific rolls that would be needed for a restoration. Soon, Kino Lorber stepped up to finance and complete the restoration.

The Queen is now widely regarded as an important historical document, and I’m happy that the Ransom Center has had a hand in preserving it and making it available to the public. It is now available on Netflix and a BluRay release is planned.

Steve Wilson is the Curator of Film at the Ransom Center.