In part one of a two-part blog post series, NEH Audio Digitization Project Coordinator Katie Quanz chronicles the progress of Unlocking Sound Stories, a NEH grant funded project digitizing and preserving more than 2000 rare recordings.

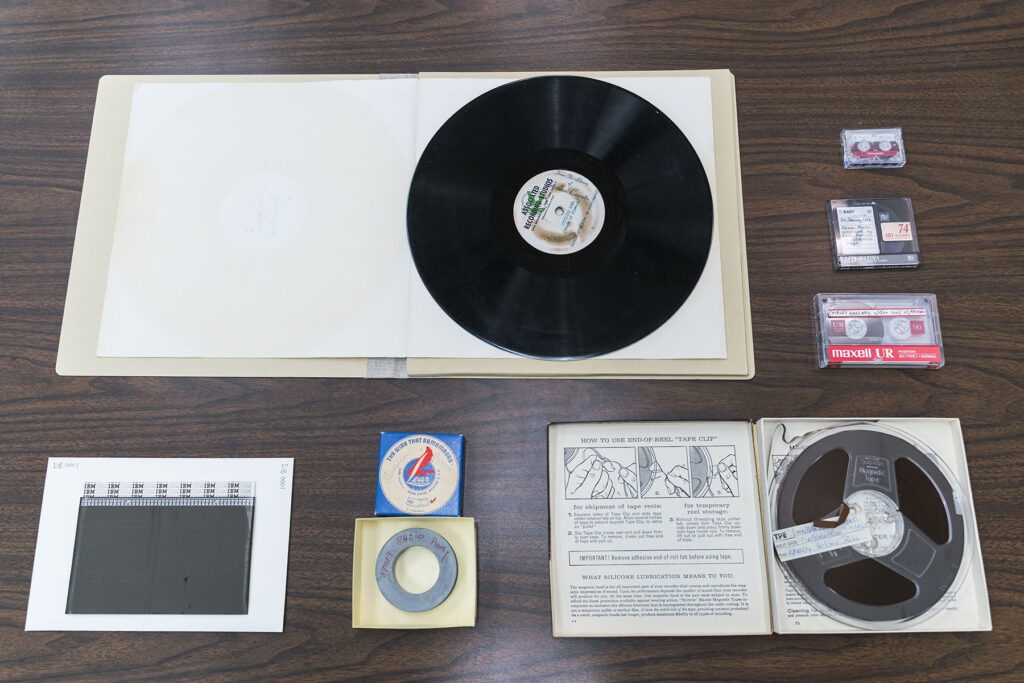

Recorded sound has a way of bringing history to life. We are able to eavesdrop on meetings and interviews, hear our favorite authors dictate their notes, and sit in on rehearsals of performances. But we can only hear these events if we are able to play the media on which the sound is stored. This is why the Ransom Center embarked on a massive digitization project in 2018. Unlocking Sound Stories, a project funded in part by a generous grant from the National Endowment for the Humanities is preserving and providing access to 2800 recordings (click here for more on the grant). Since the project commenced in fall 2018, 2100 recordings, now in digital format, have been made available in the Ransom Center’s Reading and Viewing Room; another 700 more will be added in the coming months. All of the preserved recordings will only be available onsite at the Ransom Center. Additionally, 750 recorded interviews with authors, directors, and actors conducted by New York Times theater critic, Mel Gussow will be available online. The Gussow recordings will be accessible via the Center’s digital collections’ webpage.

As both the Project Coordinator and a historian of sound technologies, I have found that the most exciting aspect of working with recorded sound is that you never quite know what will be on the recording until you listen to it. While the majority of sound recordings are labeled accurately, occasionally some hidden gems are uncovered once we are able to listen to them digitally. For instance, on one David Douglas Duncan recording, the photographer had Pablo Picasso sing his childhood lullaby. Other recordings, such as those of the Donald Albery and Norman Bel Geddes collections, contain sound effects for stage plays that provide a glimpse into what audiences heard when they saw the production performed. One of my favorite recordings is of the musical Blitz! (Lionel Bart), which Albery produced. For this show, Albery created recordings of both the draft version and an early performance of the musical. It is fascinating to listen to these recordings side by side and note the differences and similarities. Likewise, the David O. Selznick Collection contains several phonodiscs of musical recordings for his films. Based on these materials, it appears that Selznick was providing feedback on key musical moments by listening to individual takes on his own record player.

A concerted effort to digitize the Ransom Center’s 15,000 audio recordings began in 2001, and a few thousand collection items were digitized over the years. The current project, Unlocking Sound Stories, adds to these earlier efforts. By the end of this project, over 6000 of the Center’s sound recordings will be accessible to patrons. In order to meet our NEH project goal, the Center has contracted the services of MediaPreserve, a Pennsylvania-based company that specializes in digitizing a variety of audiovisual media. Even though the Center is working with a vendor, there is a significant amount of work that needs to be accomplished in-house.

Due to the large number of audio recordings included in the project, we elected to divide the materials into eight separate groups. I begin preparing each group by determining which materials to send. In order to best prioritize these materials, each item has been evaluated based on its current condition, the research significance of the collection, and the uniqueness of the potential content. The initial selection of the audio recordings was conducted in 2016 after Lauren Walker completed an NEH-funded survey of the audio collection. For this project, Walker examined each item in the collection and noted any potential preservation issues (click here for more on the survey). Afterward, the curators made a priority list of collections to digitize. One of my tasks is to ensure that we are not inadvertently digitizing mass-produced recordings or multiple copies of the same recording. Once the list for each group is complete, I collect the recordings from the stacks, re-evaluate their condition, carefully place them in prepared “totes” or boxes, and check the items out in our circulation system. After all the materials are safely parceled for their journey, Alan Van Dyke (Senior Preservation Technician) helps me palletize the boxes to ensure that everything arrives as a group. A few days later, we receive confirmation from MediaPreserve that all items were delivered and that they will begin to digitize the materials.

Once these materials are digitized, we receive a hard drive with all the files from MediaPreserve. The drive is immediately backed up to our cloud-based storage. Afterward, I check the quality of the recordings by listening to a portion of each file. During this phase, notes are made on the content of the recording, and we note any technical issues that may have occurred during the digitization of the file.

Following the completion of quality control, I prepare the digital preservation files (these are WAV files) for long-term storage. In order to ensure that every part of the file is accounted for, I use Bagger and BagIt, digital preservation software developed by the Library of Congress. This software packages all the files associated with each item into a single bundle, complete with a list of all items in the package and their checksums–a method for verifying that no bits have been lost in transfers or storage. Each item’s bundle is then uploaded to our secure cloud-based storage at Texas Advance Computing Center (TACC), where the files are safely kept until they are needed in the future.

The next step is to provide access to the newly added sound recordings. First, the access files (Mp3s) are uploaded to an internal server for use in the Reading and Viewing Room. Then, the catalogue entry is updated to ensure that the description accurately reflects what is on the recording. Where possible, I also try to add the names of the people on the recording, as well as the estimated date that the recording was made, if it was not noted by the creator.

Finally, once all of the digitized files are properly preserved and accessible in the Reading and Viewing Room, we signal MediaPreserve to return the original recordings. When they arrive at the Center, each item is carefully inspected, checked-in, and returned to the stacks.

If you are interested in preserving your personal recordings, a good place to start is with CDs and DVDs of your sound recordings, home movies, and photos. These items have extremely short lifespans, so it is a good idea to move them to cloud-based storage as soon as possible. Moreover, many people still have access to DVD drives on home computers that can be used to transfer their memories into long-term storage on a server. If you would like to get started on your own digital preservation at home, here are some great resources:

Library of Congress Guide to Personal Archiving:

http://digitalpreservation.gov/personalarchiving/

Guides to Audiovisual Formats:

https://psap.library.illinois.edu/collection-id-guide

Katie Quanz received her PhD from Wilfrid Laurier University and is the NEH Audio Preservation Grant Project Coordinator for the Harry Ransom Center. Her work on sound design history and Indigenous media has appeared in Velvet Light Trap and the anthologies Cinephemera and Voicing the Cinema. She is currently writing a monograph on the history of postproduction sound labor in Toronto and London.

This project generously funded by: