by JAMES ARNETT

“Why was it so hard to see while it was happening that that was what was happening?”

—URSULA K. LeGUIN, In and Out [1]

“What’s ‘it’–what do you mean by ‘it’?”

“O, anything–I mean–you know what I mean.”

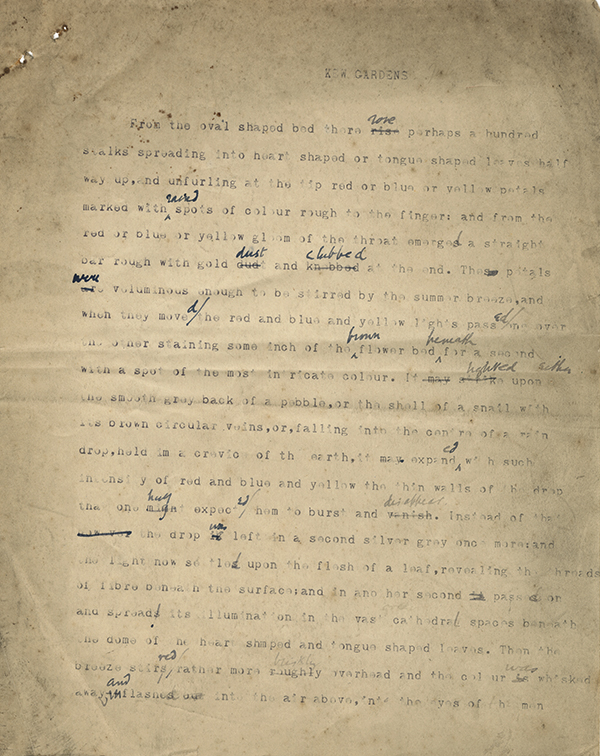

—VIRGINIA WOOLF, Kew Gardens typescript

The walls have closed in in my Tennessee home. I sometimes stand up blinking from my screen and walk from room to room, unsure of what I’m looking for or doing. My corgi, Phineas Finn, is no help, certain that if I am at home I am at his service. I stand in my front window often, looking at the unchanging suburban street. I retreat to the refuge of books.

It is 2020; it is Pandemic Time. Stop where you are; shut the doors; sit tight.

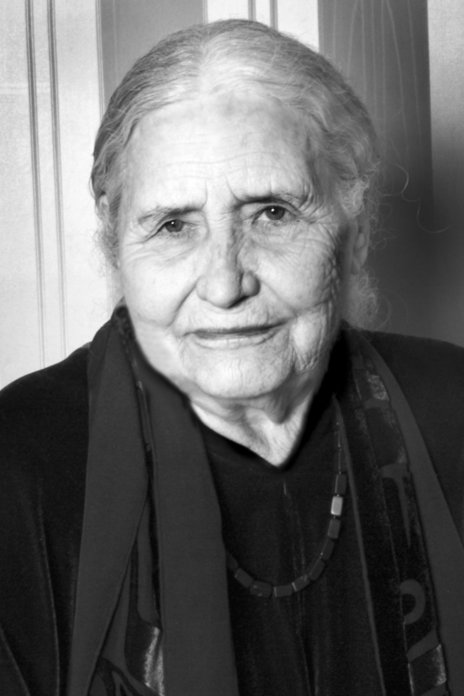

In some ways, I should know better than to do what I did—read books about plague, unrest, unraveling, the end. But I grab Katherine Anne Porter and William Maxwell; Octavia Butler’s Clay’s Ark; Connie Willis’s Doomsday Book; Lauren Beukes’s Afterland and Ben Marcus’s The Flame Alphabet; Saramago’s Blindness. And Doris Lessing, my recurrent perverse comfort. Doris Lessing cemented her reputation as a curmudgeon when, confronted by reporters on her stoop after returning home from the shopping, she was asked, trailing vegetables in her hands, how she felt to have received the Nobel Prize for Literature: (sighs; rolls eyes) “It’s been going on for 30 years.”

In productivity, Lessing was the Joyce Carol Oates of the UK (read this article via Celestial Timepiece about a meeting between the two of them in the 1970s). What drew me to the Ransom Center’s archives was its trove of unpublished Lessing works. Although she completed more than 50 books, many of which were bestsellers, and many of which are canonical now, she didn’t always succeed. I was curious—what were these failures, and what might we also learn from them?

Lessing was a self-identified Cassandra, a blithe prognosticator, a speculator. In one very early playscript— “Africa Dances” (now in the archive)—Lessing speculates about the power the Black mineworkers would have if they formed unions and withheld labor [2]. In another, the Shavian farce “£20000 of Love,” she launches a criticism of the Black African bureaucratic classes for their toadying to the British colonial class. In another unperformed script, “The White Princess,” Lessing takes a gambit from the science fictional zeitgeist, and posits a future where Black Africans have colonized space benevolently, but nevertheless reproduce the same ideologies that European colonists cultivated in Africa in reality [3]. Lessing’s early career mostly focused on African colonialism and society, bearing scathing critiques of the “colour line” (most notably in her debut novel, The Grass is Singing (1950).

An African by way of a colonial childhood in Rhodesia, Lessing was perpetually attuned to the violences built into settler colonialism; but she came to bristle at being identified as the writer of the “colour line,” instead of as an anticolonial writer. Many of her unpublished works struggle with this: these obscure treasures are often, as above, brave attempts to label and dissect the intersections of race, ethnicity, gender, economy, and ideology out of the dense weft of colonialism. Like Octavia Butler, Lessing came to identify the throbbing pulse of colonialism as the desire to know “better,” and thus to be better, and thus to exercise generosity in engendering the subjugation of Others.

A through-line in all of Lessing’s writing is just such a reckoning with the long violences of colonialism. It is not a spoiler to say that the speculative novel Shikasta (1979) ends with a global trial of colonialism: the ideas, the perpetrators, the afterlives are all put on the stand. It strikes Lessing over and over again that this is an inevitability. We have sown the seeds of catastrophe, and we shall have to figure out ways to get through the catastrophe to the other side. We must confront our participation in the violences of settler colonialism.

We are in one of the catastrophes that Nobel Prize-winning author Lessing Cassandra’d for decades, writing book after book extrapolating the consequences of our social sins. The twentieth century, Lessing insisted, was unparalleled both for its violence (the global scale, the horror)—and for the long-term consequences of its obsession with violence. Her early autobiographical novel series, where Lessing enters the texts under the fictional guise of Martha Quest, Rhodesian malcontent, was called Children of Violence. The legacy of violence is generational, extrapolates itself: she learned this at the wooden foot of her WWI-veteran-cum-Rhodesian-colonist father.

Lessing came of age in World War II, and her most famous novel The Golden Notebook (1962) (public library) softly fictionalizes and violently fragments, her experience with global warfare from the colonial periphery. The Children of Violence series (1952—1969) takes a similar turn from the autobiographical to the speculative, taking readers on an arc from a colonial African childhood into a post-apocalyptic society buckling under the schizophrenia of its inconsistencies. By the end of the Four-Gated City (1969), the survivors emerge blinking out of the rubble of a ruined world, left to their own devices to survive as best they can. The novel’s veering toward the supernatural and speculative signals, too, the turn in Lessing’s career as she moves from the catastrophes we do know to the immanent, and imminent, catastrophes we haven’t yet acknowledged.

Lessing’s subsequent novel—Memoirs of a Survivor (1974) (public library)—ostensibly picks up where Children of Violence leaves off: in a world fundamentally changed by catastrophe. Although there aren’t many explicit biographical touchstones in Memoirs, it was written, she has claimed, as “an attempt at autobiography.” But the novel is also one of Lessing’s earlier experiments with speculative fiction—an attempt to extrapolate out from current circumstances a possible future world. The world Lessing saw was rarely flattering—she was no utopian, certainly.

Speculative fiction is a tricky genre to write – it arguably has a higher failure rate than most literature: it not only has to ring true, but may eventually be judged against its prescience. What of, for instance, the many science fiction writers of the 1960s and 70s who predicted the end of civilization in a recurring Ice Age? At present, that apocalypse seems quaint.

How does the world end? Is the world ending?

“A million people. I try to take it in. The people that were milling around in this flat are alive. But the unlucky ones are dead. Why one alive and one dead? It makes no sense to me at all. Out in the streets at night, all the rioting and shooting and then someone dead on the pavement. It might just as well be me. I went out last night. Curfew or no curfew, I walked about the city. All night. Soldiers. Trucks. Shooting. I did not even cover my face. No one saw me. I walked back into this flat this morning quite alive thank you. Well, answer that whoever you are.”

—DORIS LESSING, Shikasta

In the 1980s, writing against the escalating Cold War proxy war in Afghanistan, Lessing reflected, “You could say,” by the mid-1980s, that “the whole world has become Cassandra, since there can be no one left who does not see disasters ahead. They are all of them preventable, preventable” (Wind Blows Away Ours Words 16). In a world suffused with information, and in a world wherein that information is dispersed globally, we are all Cassandras.

We are both responsible to, and also should not be held responsible to, the work of prognostication. With so much information at our fingertips, how could we not know what we are in for? But with so much information, how to distinguish the screams of the prescient from the barks of the false prophets? Where once prophecy was the special skill of a few chosen amongst us, “Once upon a time, there were the special, talented-for-prophecy individuals. Then, a few people in every palace, settlement, farmstead. But now, a multitude.

These days… Cassandra is a shout of warning coming from everywhere, particularly from scientists whose function it is to know what is likely to happen, from people everywhere who concern themselves with public affairs, anyone who thinks at all” (Wind 16). How do we not buckle under the weight of thinking about all of this all of the time?

What is the matter with us all? (Wind 17 – public library)

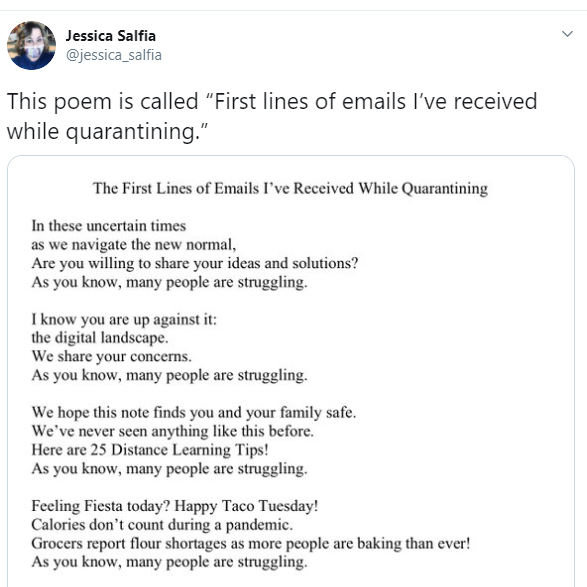

“We all remember that time. It was no different for me than for the others,” Memoirs of a Survivor begins, establishing the common time of catastrophe wherein we’re all bereft, looking for Reason or reasons for our suffering. “Yet we do tell each other over and over again the particularities of the events we shared, and the repetition, the listening, is as if we are saying, ‘It was like that for you, too? Then that confirms it, yes, it was so, it must have been, I wasn’t imagining things.’” [3] Catastrophe would seem to exceed language, or at least court the unsayable. We are now living in times that seem to require euphemism. Read this viral poem via Twitter about the quarantine by Jessica Salfia, that uses the hashtag #teachlivingpoets.

These uncertain times, a poem

everything going on

what with what’s going on

you know, all that’s going on

times like these, with all that’s going on

during this time with everything going on

right now, during all this going on

—JAMES ARNETT, 2020

Unlike others of Lessing’s novels—the sly and ambitious Shikasta (1979), the climate change fable Mara and Dann (1999)—there is no telling what caused The End in Memoirs. What is the “it” that has brought us low? “One of the things we now know was true for everybody, but which each of us privately thought was evidence of a stubbornly preserved originality of mind, was that we apprehended what was going on in ways that were not official.” [4] In The Golden Notebook, one of Anna Wulf’s therapeutic exercises is to clip and collect the various terrifying headlines of the time – rife with fears about nuclear war, ideological conflicts, genocides. Ostensibly, she is meant to feel better about her world-historical fears if she can see them all in one place. It feels now like doomscrolling ahead of the curve.

Time is moving more slowly now, it feels. Countless memes chime in that it feels like we’re still in March—when “it” all got started, when we went indoors, when we learned to be afraid of “it.” In the wake of catastrophes, in their long tedious durations, Lessing observes, it bears commenting “on the way we—everyone—will look back over a period of life, a sequence of events, and find much more there than they did at the time” [4]. The time of catastrophe, the time of “all this that’s going on,” of ‘it,’ is fuller than we can know at this moment. But we shall look back, Lessing observes, and see a richness there. In Memoirs, the unnamed narrator, a middle-aged single woman, finds herself anchored to a crumbling apartment in the midst of a slowly unfolding disaster.

Lessing’s narrator muses, “I think this is the right time to say something more about ‘it.’ Though of course there is no ‘right’ place or time, since there was no particular moment that marked ‘its’ beginning. And yet there did come a period when everyone was talking about ‘it’; and we knew we had not been doing this until recently: there was a different ingredient in our lives.” (150) “It” is not any one thing, it’s all the things; it crept up on us, and took our lives over, but “it” is not the same as “it” was a few months ago. Has it gotten worse? What is “it”?

“Perhaps it might even have been more correct to have begun this chronicle with an attempt at full description of ‘it,’” Lessing reflects. “But is it possible to write an account of anything at all without ‘it’—in some shape or another—being the main theme? Perhaps, indeed, ‘it’ is the secret theme of all literature and history, like writing between the lines in invisible ink, which springs up, sharply black, dimming the old print we knew so well, as life, personal or public, unfolds unexpectedly and we see something where we never thought we could—we see ‘it’ as the ground-swell of events, experience… Very well, then, but what was ‘it’?” (150-151) Is “it” happening to “us”? Who are “we,” that we’re experiencing “it?” And what, after all, isn’t about it? Lessing posits that all of literature is about (an) “it,” a referent that we all know or think we know or fear we don’t know. “It’s” always happening, whatever “it” might be. We are in it.

“’It,’ in short, is the word for helpless ignorance, or of helpless awareness. ‘It’ is a word for man’s inadequacy?” (151) Helpless ignorance, or helpless awareness: helplessness is “it.” Or at least that is what They would like us to believe—they, the “Talkers,” as the narrator names “the kind of person who ran things, administered, sat on councils and committees, made decisions. Talked.” (104)

When has this ever been different? “It’s” always with us. “Has there been a time in our country when the ruling class was not living inside its glass bell of respectability or of wealth, shutting its eyes to what went on outside? Could there be any real different when this ‘ruling class’ used words like ‘justice,’ ‘fair play,’ ‘equity,’ [law and] ‘order,’ or even ‘socialism’? Used them, might even have believed in them, or believed in them for a time; but meanwhile everything fell to pieces while still, as always, the administrators lived cushioned against the worst, trying to talk away, wish away, legislate away the worst—for to admit that it was happening was to admit themselves useless, admit the extra security they enjoyed was theft and not payment for services rendered…” (105) There are those of us living through ‘it,’ those of us pretending ‘it’ isn’t actually happening, those of us who don’t even have to pretend to pretend ‘it’ isn’t happening (to Them). In “times like these,” when we’re naming what “it” is that “we” are going through, we are probably already behind the curve.

Virginia Woolf, in her essay “Thoughts on Peace in an Air Raid,” remarks on the Authorities of her time—of the Blitz—“There is no woman in the Cabinet; nor in any responsible post. All the idea makers who are in a position to make ideas effective are men. That is a thought that damps thinking, and encourages irresponsibility. Why not bury the head in the pillow, plug the ears, and cease this futile activity of idea making? Because there are other tables besides officer tables and conference tables.”

There is the kitchen table in my sister’s house, for instance, where I sit with my niece as she Zooms her second-grade class, learning about homes, habitats, niches. My niece’s niche is determined by the smiling faces of other children arrayed on the screen in front of her. “What is a habitat?” I ask her; they’re learning about the conditions of life. “Where animals live. Water…food. Shelter,” she responds, pulling her headphones down around one ear. “And trees, for air. Because if we ran out of trees and plants, we’d die: we wouldn’t have clean air to breathe.”

Me: “So a habitat is where we have all the things we need in order to live the lives we live?”

Anneliese: “Yes! And everybody should have what they need to live.”

Anneliese for President, 2048.

In the temporality of “it” in Lessing’s Memoirs of a Survivor, society is slowly breaking down. The unnamed middle-aged woman narrator is staying in a block of middle-class apartments in an unnamed city. Most other cities have begun to empty; many of the people have banded together in the disorder and fled to the country. Bands and tribes and clans are materializing in the disarray of the catastrophe. Resources are bartered for, scavenged, looted. Services are spotty. Violence is unpredictable. Catastrophe is the order of the day.

The narrator proposes at the beginning of the tale, “I shall begin this account at a time before we were talking about ‘it’. We were still in the stage of generalized unease. Things weren’t too good, they were even pretty bad. A great many things were bad, breaking down, giving up, or ‘giving cause for alarm,’ as the newscasts might put it. But ‘it,’ in the sense of something felt as an immediate threat which would not be averted, no.” [5] When does “it” start, properly? When is “it” already in motion, already arriving, already here? Is there a “before it”? Or an “after it”? Woolf, again, writes, scathingly a propos of our milieu of denial, “do the current thinkers honestly believe that by writing “Disarmament” on a sheet of paper at a conference table they will have done all that is needful?”

During Memoir’s unspecified catastrophe, “Attitudes towards Authority, towards Them and They, were increasingly contradictory, and we all believed we were living in a peculiarly anarchistic community. Of course not. Everywhere was the same… We were still in the stage of generalized unease.” [5]

People in my neck of the woods initially hedged against talking about a Pandemic, or Unrest, or even a Catastrophe, preferring instead the euphemistic, “what with all that’s going on,” or “given everything that’s happening,” or in the emergent corporate-speak, “in these uncertain times.” Of course, what we’re calling what we’re going through has become deeply polarizing, a political litmus test that implicates disparate discourse bubbles.

All of the “official” accounts in Lessing’s catastrophe, are inadequate to the task of describing what is. They relay events in the language of history, of timelines, and ape the omniscience that allow them to claim the “official” account of the catastrophe to begin with.

But Lessing knows that our experience of catastrophe is far more individuated than that—far more idiosyncratic, local, parochial. We stitch together the events of the day in order to uncover the reason that strings them all together. “Newscasts and newspapers and pronouncements were what we were used to, what we by no means despised: without them we would have become despondent, anxious, for of course one must have the stamp of the official particularly in a time when nothing is going according to expectation. But the truth was that every one of us became aware at some point it was not from official sources that we were getting the facts that we were building up into a very different picture from the publicized one.” [4–5]

For weeks, I pored over the pandemic statistics—how many tested, how many infected, how many hospitalized, how many dead. The numbers, it is their nature, always climb. The national figures and the international figures dance around your state or territory figures, your county or conurbanity figures. Rates of infection become more critical than sheer numbers of infected, but both of these rates are forever spun by forces that only occasionally announce their fungibility.

“People,” in Lessing’s Catastrophe, “did not act on what they heard, that is the point—unless they had to…And yet in a way everybody played a part in this conspiracy that nothing much was happening – or that it was happening, but one day things would go into reverse and hey, presto! Back we would be in the good old days. Which, though? That was a matter of temperament: if you have nothing, you are free to choose among dreams and fantasies… I played the game of complicity like everyone else. I renewed my lease during this period, and it was for seven years: of course I knew we didn’t have anything like that time left.” (9; 106-107)

What to do, what to do?

The narrator, like myself, finds herself staring at the walls often – “I would stand in my living-room… [and] I would wait there, and look quietly at the wall.” (11) What else is there to do when there’s nothing to be done? Virginia Woolf’s “The Mark on the Wall” has never felt more speculatively prescient: “Perhaps it was the middle of January in the present year that I first looked up and saw the mark on the wall,” although perhaps it wasn’t. Perhaps it was March 2020 when I looked up and saw the mark on the wall. Perhaps it is March, 2020, still.

Oh! dear me, the mystery of life; The inaccuracy of thought! The ignorance of humanity!

—VIRGINIA WOOLFThe Mark on the Wall

Like Woolf’s contemplative surrogate, Lessing’s narrator is both captivated and underwhelmed by the sights on offer: “there is nothing I can think of to say about this wall that could lift it out of the commonplace. Yet, standing there and looking at it, or thinking about it while I did other things about the flat, the sense and feel of it was always in my mind, was like holding to one’s ear an egg that is due to hatch… I even found I was putting my ear to the wall, as one would to a fertile egg, listening, waiting” (11–12). What lies on the other side of our walls? What is the horizon currently obscured by our alienation?

The outside world feels terrifying right now. It’s hard during these times to sort out what is justifiable fear, and what burgeoning agoraphobia. “One morning I stood with my after-breakfast cigarette… and then I was through the wall and I knew what was there,” Lessing’s narrator recounts. “There was a sweetness, certainly—a welcome, a reassurance… I was left with the conviction of a promise, which did not leave me, no matter how difficult things became later, both in my own life and in these hidden rooms.” (13–14) When there’s nowhere else to go, go to the wall—and through it. Although these times are hard, Lessing’s narrator sees on the other side of the wall the promise that introspection will yield comfort, insight, even as it may also disturb. Lessing boldly tells us that we cannot recuse ourselves from introspection.

For what Lessing’s narrator sees on the other side of the wall is life itself—the lives we live, the lives we have lived already, the lives we might yet live. She sees her past, and others’; and sees a future, too, but not that future the Talkers are conjuring up in the thinness of ideas, words, rhetorics, politics. The walls can close in, but as my niece Anneliese says, with a blank wall, “you can imagine so much. Sometimes when I stare at the wall, I feel like a monster might come out of it. Or chickens! Or flowers, or birds.”

I’m hoping for the flowers and birds, myself. We all live with our monsters already. In the meantime, good luck with it, with all this going on; let a book be your wall; let Lessing take you, unsentimentally shaking her kohlrabi in your face and say: “This is it.”

[1] LeGuin, Ursula K. “In and Out,” in Searoad, Harper, 1991, p. 56.

[2] Arnett, James. “Colonizing, Decolonizing: Africans from Space and African Colonialism in Doris Lessing’s Unpublished Screenplay The White Princess,” Journal of Screenwriting Vol. 10, No. 1, March 2019, pp. 81-95.

[3] Arnett, James. “African, Communist: Situating Doris Lessing’s ‘Africa Dances’,” Doris Lessing Studies Vol. 35, Winter 2017, pp. 15-23.[4] Lessing, Doris. Memoirs of a Survivor, (Knopf, 1975) and (Vintage, 1988.)

[5] Lessing, Doris. Shikasta (Vintage, 1981.)

[6] Lessing, Doris. The Wind Blows Away Our Words. Vintage, 1987.

[7] Woolf, Virginia. “The Mark on the Wall,” in Monday or Tuesday (1921).

[8] Woolf, Virginia. “Thoughts on Peace in an Air Raid,” https://newrepublic.com/article/113653/thoughts-peace-air-raid/

Top image: First edition of Doris Lessing’s novel The Golden Notebook (London: Michael Joseph, 1962). Harry Ransom Center Book Collection.