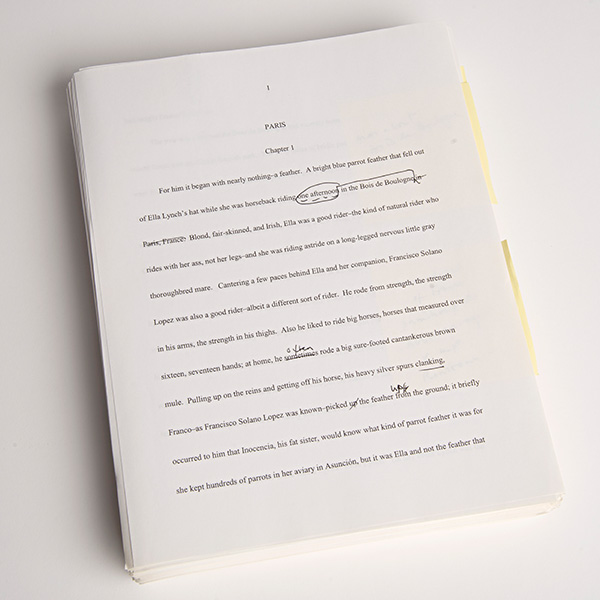

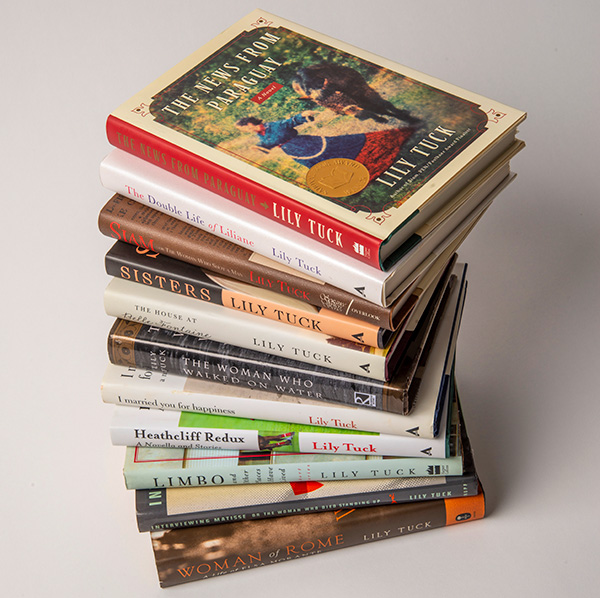

The Ransom Center is now home to the papers of National Book Award–winning writer Lily Tuck. Tuck is the author of seven novels, including The News from Paraguay (2004), Siam or The Woman Who Shot a Man (1999), I Married You for Happiness (2011), and Sisters (2017); three story collections, including her most recent book Heathcliff Redux: A Novella and Stories (2020); and the biography Woman of Rome: A Life of Elsa Morante (2008). Her archive offers a fascinating record of her career through manuscripts and drafts, unpublished stories, notes, research materials, and correspondence with authors and editors such as Roger Angell, Elizabeth Hardwick, and Gordon Lish, among other materials. Shortly after the arrival of her papers at the Ransom Center, Lily Tuck answered a number of questions about her writing life and her archive.

Megan Barnard: When you received the National Book Award in 2004 for The News from Paraguay, you noted in your acceptance speech that you had never been to Paraguay. Soon thereafter, you received an invitation to visit from the Paraguayan government. Can you tell us about that visit and what it was like to be in Paraguay after you’d written your novel?

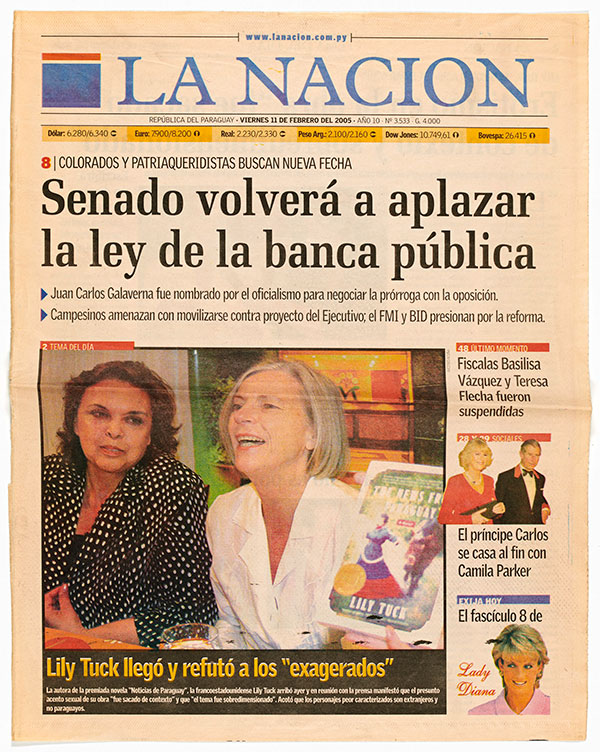

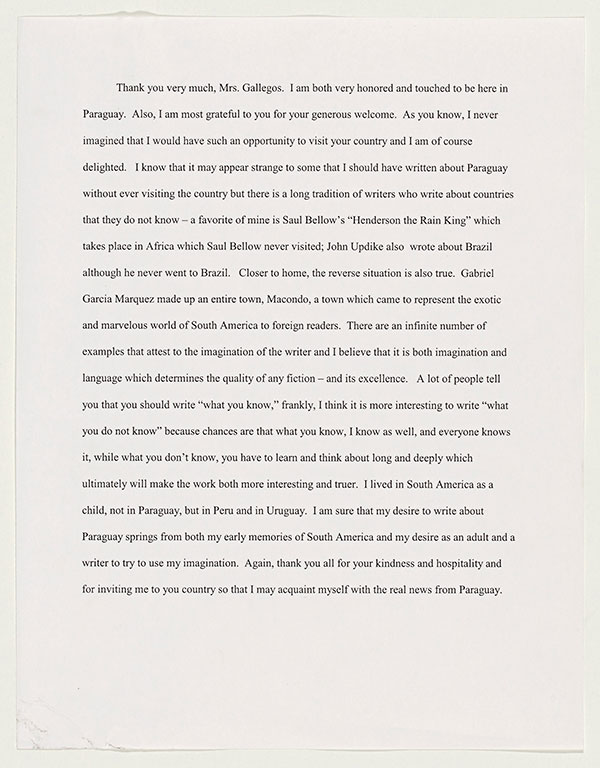

Lily Tuck: The Paraguayan Government invited me to visit a few months after I won the National Book Award. With a certain amount of trepidation (and a bad cold), I flew to Asunción where I was met with a storm of criticism. Naively, I had had no idea that the central figure of my novel, the dictator Francisco Solano López, was still considered, by many people in Paraguay, a hero. Already, articles had been written in the local newspapers and complaints aired on the radio by prominent citizens objecting to both the book and my visit—never mind that the book had not yet been translated into Spanish and was for the most part unread. Immediately on my arrival, I was accused of slander and immorality. It got worse—Mierda, go home, someone called my hotel room, threatening me. During a press conference, I was questioned by hostile journalists who reproached me for writing sex scenes and berated me for having so little knowledge of their country and their language. The fact that I had lived in Peru for four years as a child was no excuse and the Spanish—not to mention Guaraní—I had learned then was mostly forgotten. In the end, however, the journalists’ questions grew less hostile as it became clear that I was not an intimidating presence—I repeatedly mentioned that I was also a grandmother—or a writer with a political agenda.

During my first few days in Paraguay—accompanied for my safety by a bodyguard—I was shown the sights in the capital, especially those that pertained to my novel—López’s palace, the house Eliza Lynch (Francisco Solano López’s beautiful Irish mistress) had lived in, the Recoleta cemetery where she is buried (she died in Paris but eventually was reinterred in Asunción). Then, for the remaining days of my stay, I was flown in a small private plane, together with Evanhy de Gallegos, the Minister of Tourism, a photographer (every day my visit and exploits were featured in the Paraguayan newspapers), a historian, Miguel Àngel Solano López, the great grandson of the dictator and a diplomat, Liz Crámer, my kind and lively translator, and the ever present bodyguard—all of whom were excellent company—to the seventeenth-century Jesuit missions, the War of the Triple Alliance battle sites I had written about, and, finally, to the magnificent Iguazu Falls. And, all the while, I who don’t particularly like to fly, always dreading the worst, had a most memorable and wonderful time.

You later established the PEN/Edward and Lily Tuck Award for Paraguayan Literature, supporting the translation of Paraguayan works from Spanish or Guaraní into English. What inspired you to establish this award? Is there a Paraguayan author or work you would especially recommend to readers?

For once, I sold a lot of copies of The News from Paraguay as well as translation rights so when I got home from Paraguay, I wanted to show my thanks for the welcome and give back to the country and its people a bit of my good fortune. Under the auspices of PEN America, I set up a modest prize—The Edward and Lily Tuck Award for Paraguayan Literature—of $3,000 to be given every other year to a work of literature by a Paraguayan writer, in order to assist the translation of the work into English.

As for a Paraguayan writer—I very much like and admire Augusto Roa Bastos who wrote Il Supremo, an inspiration!

For the first time ever, all the nominees for the National Book Award for Fiction in 2004 were women, and you all lived in New York City. What was it like being a nominee that year?

It was exciting and surprising. Christine Schutt, Joan Silber, Kate Walbert, Sarah Shun-lien Bynum, and I, the five finalists, received a lot of publicity—albeit most of it negative—from newspapers, magazines, and by a few disgruntled prominent writers. The main complaints were that we were not well-known, that we had not sold many books, and, finally, I suppose, that we were women and all living in New York City. Feeling wronged by this unexpected and misguided attention, we right away allied and supported each other—we did readings together, talked on the radio, appeared on television—and better still, we became friends. At least once a year we get together—this month, fully vaccinated, we will meet for dinner!

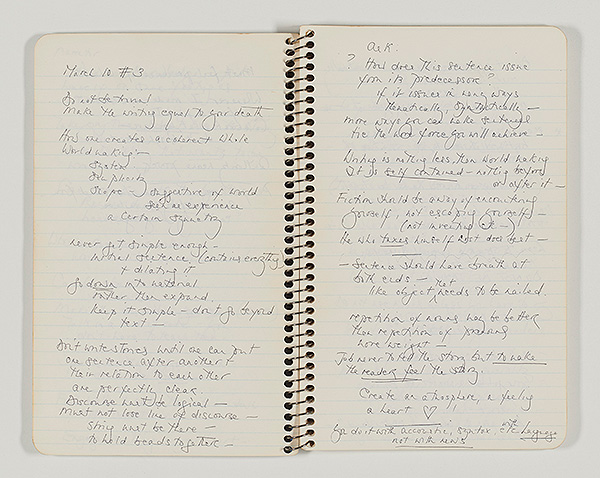

In 1989, you participated in a writing seminar with editor Gordon Lish, and your archive includes your notes about his teachings and your discussions. How did that seminar influence you as a writer?

I had struggled as a writer and had never taken a writing class, but I heard about Gordon Lish and was intrigued by his reputation as an unconventional teacher. His class met once a week for twelve weeks, for six hours—from six to midnight—without a break. I will never forget how Gordon could talk seamlessly for hours, exhorting us to “learn to behave importantly,” “to make the writing equal to our death,” “to scream from the rooftops, burn down the churches.” He would then have each of us read from our work—an anxiety producing and often mortifying experience—as his criticism was harsh and final. People left the class in tears. His teaching, for me, was both an education—“great writing is logical discourse, logically rendered”—and a revelation—“writing is an act of seduction.” More specifically, Gordon taught me how to open up a sentence and how to recast a sentence; he taught me how to come to the page without an agenda and without pettiness. Best of all, he taught me that being a writer is a sanctuary and that I am lucky. I am lucky, too, that Gordon, an editor at Knopf at the time, published my first novel, Interviewing Matisse or The Woman Who Died Standing Up.

You made use of the Alfred A. Knopf Records housed at the Ransom Center while researching for your 2008 book Woman of Rome: A Life of Elsa Morante. How was the Knopf archive helpful to your research about Morante?

I was writing about how happy Elsa Morante was about being published in English by Alfred A. Knopf and, likewise, how happy Blanche Knopf was to publish Morante’s novel Arturo’s Island. The Ransom Center had the letters Blanche Knopf wrote to Morante which attested to their mutual happiness as well as to their friendship and I was able to use them to advantage in my biography.

Your 2015 book The Double Life of Liliane is a novel centered on your personal and family history. How do autobiography and the imagined, or fact and fiction, blend together in this book? In your “Author’s Note” for The News from Paraguay, you wrote, “What… the reader may wonder, is fact and what is fiction? My general rule of thumb is whatever seems most improbable is probably true.” Does this sentiment hold true for The Double Life of Liliane?

That statement does not really apply to The Double Life of Liliane, as the events described are mostly probable. The problem, for me, writing The Double Life of Liliane was describing events that had occurred before I was born or when I was not there. And rather than inventing them out of, say, whole cloth, I tried to imagine them as truthfully and accurately as possible while, at the same time, trying to bring them alive on the page.

The Double Life of Liliane opens with two epigraphs, one of which is by Gabriel García Márquez:

I believe one has a public life, a private life and a secret life.

I have written a lot about my public and private lives.

On my secret life, I have not written a single word.

Why did you choose this quotation for the opening of the book?

I am a private person and I would never write about myself in a revealing way—events, facts, about my life, yes, but not my innermost thoughts or feelings.

The poet Frederick Seidel wrote a poem about you. Can you tell us the story about that poem?

Fred Seidel and I were both undergraduates at Harvard and were friends. He gave me many books, including Robert Lowell first editions which I still have. He wrote a poem about me comparing me to a seal in the Central Park Zoo, but I no longer have the poem—something perhaps about my being “sleek” but I don’t remember….

What do you hope students, researchers, or readers might learn from your papers?

I came to writing late—marriage, children, divorce, single motherhood interfered. I don’t regret this. Nonetheless, I always wanted to write and, perhaps, my archives will show that—although it may sound like a horrible cliché—it is never too late if one wants it enough, and I did.