by CLARE HUTTON

Introduction by Gregory Curtis

Giving Ulysses to the World

February 2, 2022, will mark one hundred years since the publication of a book that changed literature forever. Irish novelist James Joyce’s pioneering modernist novel, Ulysses, was a labor to write and more so, perhaps, to publish.

Joyce scholar Clare Hutton wrote about the novel’s complex publishing history in her 2019 book, Serial Encounters: Ulysses and The Little Review, which gives a thorough account of key women in Joyce’s life who helped his now almost hallowed masterpiece reach readers of the early twentieth century.

Nora Barnacle, Joyce’s partner beginning in 1904 until his death, was enormously important in practical and emotional ways. But, as important to his literary success were Margaret Anderson, Jane Heap, Harriet Shaw Weaver, and Sylvia Beach.

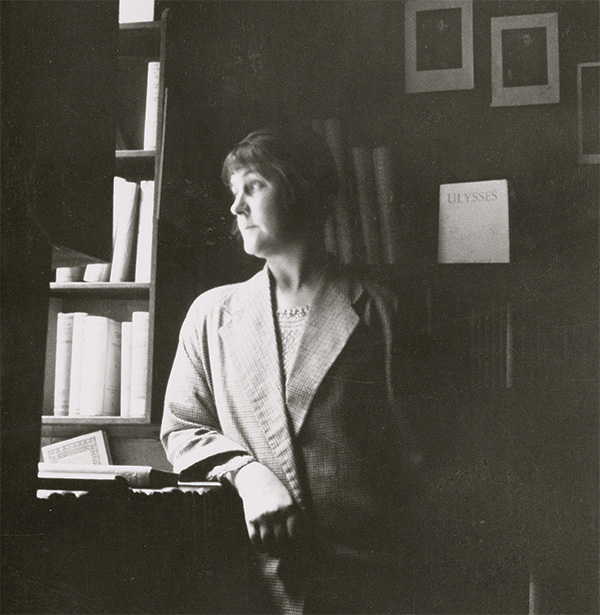

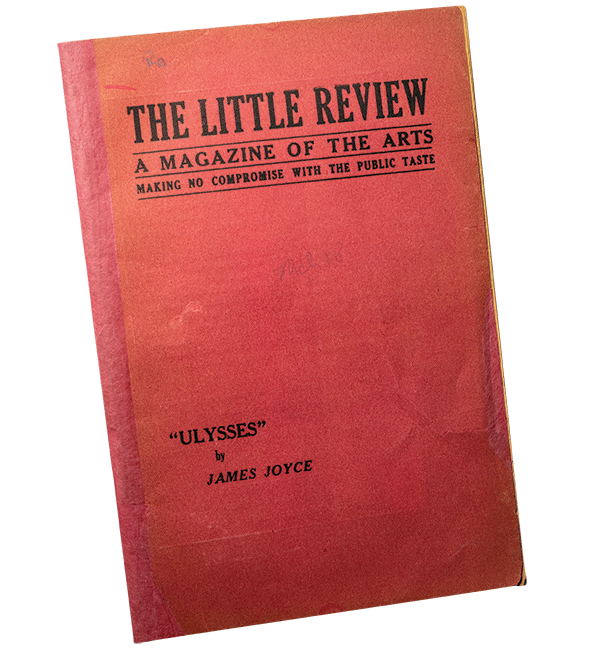

In New York, portions of Ulysses were published in Anderson and Heap’s The Little Review, and in the UK, Shaw Weaver committed to substantial, and initially anonymous, financial support of Joyce, while publishing excerpts of Ulysses in The Egoist. It was American Sylvia Beach who finally published the novel in its entirety in 1922. She ran Shakespeare and Company, an English-language lending library and bookshop at 12 rue de l’Odeon in Paris until it closed in 1941.

The Ransom Center’s Maurice Saillet collection contains significant materials documenting Beach and her activities as the first publisher of Ulysses. Items related to the women who helped publish Ulysses and from the Center’s extensive James Joyce collection will be included in the exhibition, Women and the Making of Joyce’s Ulysses, curated by Hutton, who teaches English at Loughborough University, beginning January 29, 2022.

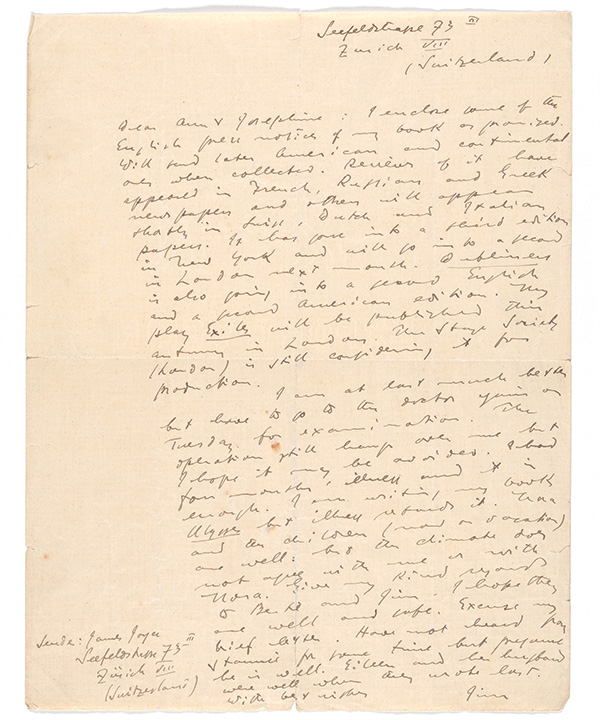

James Joyce made frequent observations about the “actual difficulties” of his life. Between 1914 and 1921, when he was at work on Ulysses, his letters were full of complaints about inadequate living quarters, problems with his health, and perennial shortages in cash.

In November 1921, he told Harriet Shaw Weaver, his generous financial patron and tireless publisher, that he was finishing Ulysses “amid piles of notes at a table in a hotel” and against a “good deal of latent hostility towards the book among men of letters.” As is so often the case with James Joyce, the truth is rather more complicated. By the time he was finishing what has become known as the world’s most famous Irish novel, Joyce had garnered steadfast material and practical support from many sources, including a notable quartet of women who helped to see the work into print.

It is certainly the case that there were men facilitating Joyce’s work too. Ezra Pound helped to arrange the serialization of Ulysses in The Little Review, the avant-garde New York journal edited by Anderson and Heap. John Quinn, attorney and manuscript collector and financial patron, defended Anderson and Heap when they found themselves in a New York court in the spring of 1921, charged with the offence of publishing installments of Ulysses deemed to be obscene. The roles played by Pound and Quinn are well known, and well documented within literary history.

The roles played by the women behind the scenes are somewhat under-acknowledged. It is a fact of some cultural irony and considerable cultural significance that three of these women—Margaret Anderson, Jane Heap, and Sylvia Beach—were American and openly gay. The fourth, Harriet Shaw Weaver, was British, single, and a woman with a considerable unearned income, that she directed towards Joyce, in increasing sums from 1916 onwards. The Women and the Making of Joyce’s Ulysses exhibition will celebrate the role that women played in the realization of Joyce’s pioneering work. The exhibition will reveal a more social story of how Ulysses came into being, and unpack an image and myth that Joyce cultivated quite strongly: that of the lone genius in a European attic struggling with a public and publishers who failed to recognize his genius, and wished to thwart and silence his valiant authorial efforts.

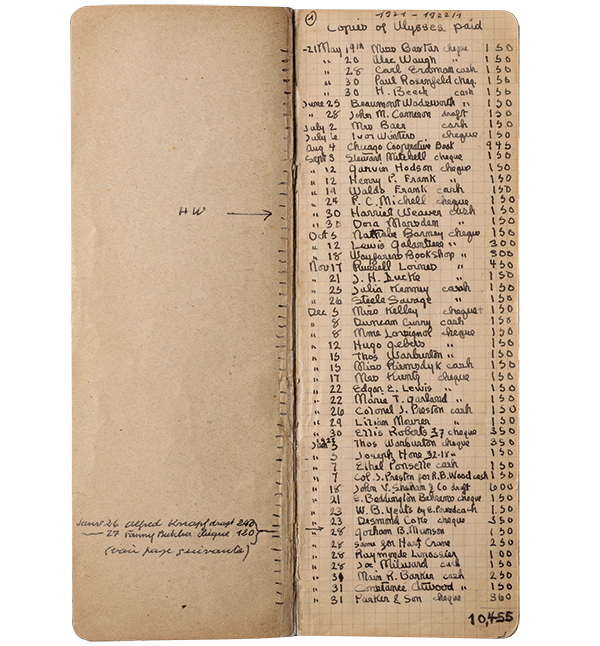

The Ransom Center holds many remarkable objects that help to tell this story including unpublished correspondence from Joyce and others within his circle, photos, manuscripts, and ephemera. One item of particular and unique significance is Sylvia Beach’s handwritten notebook of subscribers to the first-edition of Ulysses, which she published from her Paris bookshop, Shakespeare and Company, on February 2, 1922, the occasion of Joyce’s 40th birthday.

A committed reader of modernist literature and a believer in the values of female suffrage and universal free speech, Beach knew who Joyce was when she first met him at a party in Paris in the summer of 1920. Joyce and his family had just arrived in the city after periods living in Trieste and Zurich, and he quickly became a regular at Shakespeare and Company, where Beach proved to be a sympathetic listener to stories about the ongoing difficulties he was facing in relation to the Ulysses serialization in The Little Review. By April 1921, she had agreed to publish the first edition and was correct in recognizing that Ulysses, as she told her sister Holly, “is going to make my place famous.” There’s still a Shakespeare and Company in Paris although at a different address, and copies of that first edition are prized among book collections all over the world, including those at the Ransom Center, which holds more than 40 copies of this most iconic first edition.

While Beach’s role as “midwife of modernism” is undoubtedly significant, it is also true that there would have been no Ulysses to publish had Joyce not benefitted so significantly from the patronage of Weaver, a far more shadowy figure, but one of equal importance. The role played by Anderson and Heap as editors of The Little Review and the very first publishers of Ulysses is also exceptional. They greeted Ulysses with energy and enthusiasm and found an appreciative readership for Joyce’s work in the U.S. There can be no doubt that their efforts and the experience of being regularly published in The Little Review spurred Joyce in his lengthy compositional labors.

Women played crucial supporting roles in Joyce’s personal life too, and the exhibition will focus, in particular, on three important and often overlooked figures: Joyce’s mother, his Aunt Josephine, and Nora Barnacle, his longstanding partner whom he first dated on June 16, 1904, the day on which Ulysses is set.

Joyce’s father has been celebrated in several books. His mother, who died in August 1903 at the age of 44, after perhaps as many as 17 pregnancies, has been all but forgotten in Joycean biography. Joyce’s correspondence with her reveals a deep emotional and practical connection, and will be on display alongside pages of Ulysses in which her death is so deeply remembered.

The exhibition will also consider the role played by Nora—a model of a kind for Molly Bloom—and the woman at the absolute heart of Joyce’s emotional life. Within weeks of their meeting, Joyce told Nora that he saw his mother as a “victim,” and “cursed the system which made her a victim.” Certainly one can see that the choices they made as parents and partners as a deliberate turning away from the much more traditional and limited life they might have had had they stayed in Dublin.

Yet Dublin ways followed them to continental Europe, and Joyce clearly depended on the advice and goodwill he received from the Dublin-based Aunt Josephine, a regular correspondent, and yet another woman who facilitated Ulysses through acts of unstinting loyalty, practical support, and tireless emotional resilience.

In focusing on such acts, and showing different items of testimony, Women and the Making of Ulysses will enable new ways of seeing the work in context. No prior knowledge of either Ulysses or Joyce is assumed in the exhibition layout, as the focus is on the context rather than the content of the work. The aim is to engage broad, diverse, and intergenerational audiences, including anyone with interests in gay culture, feminism, the representation of female experience, Irish literature, and modernism.

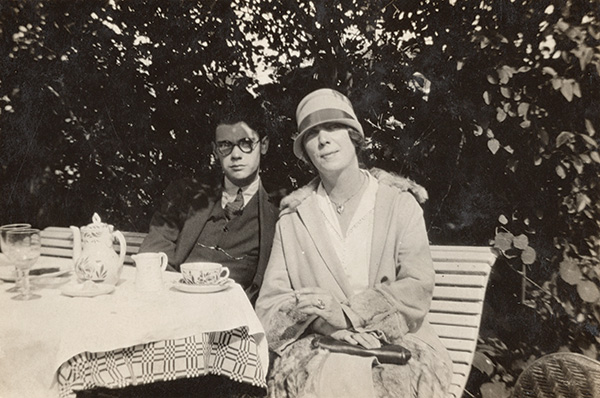

Top Image Featured:

Sylvia Beach and James Joyce in the doorway of Beach’s Paris bookshop, Shakespeare and Company, Alliance Paris, 1922. James Joyce Literary File Photography Collection, Harry Ransom Center.