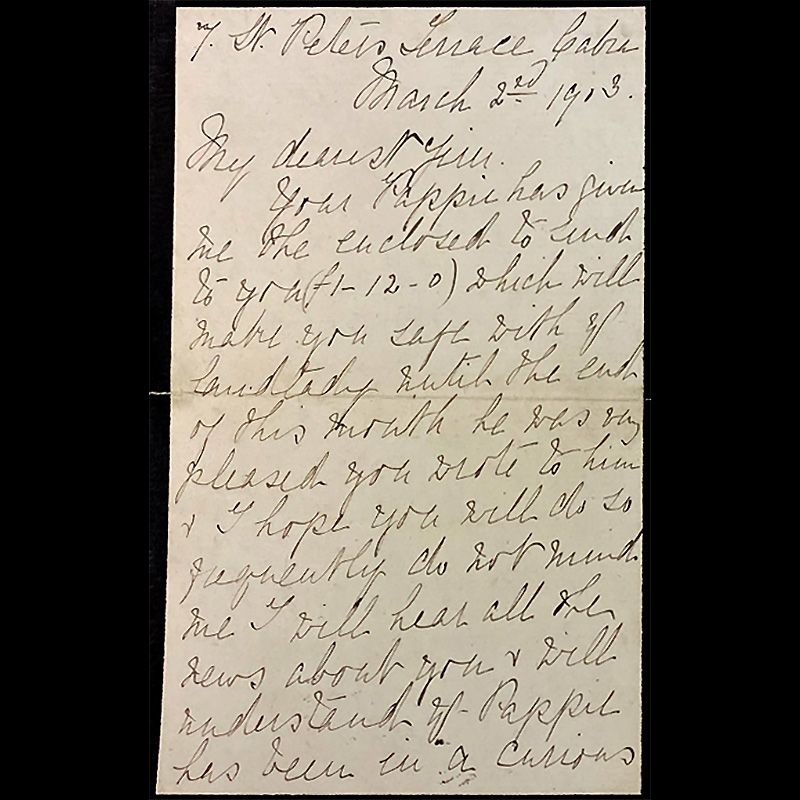

Page 1 of a letter from Mary Jane Joyce to James Joyce, March 2, 1903. Cornell University Library, Division of Rare and Manuscript Collections.

# 3: Letter from Mary Jane Joyce to James Joyce, March 2, 1903.

by CLARE HUTTON

This is the third article in a series devoted to objects that tell the story of women who supported author James Joyce and the publication of his landmark novel, Ulysses (1922). Learn more in the exhibition, Women and the Making of Joyce’s Ulysses, curated by Dr. Clare Hutton and on view through July 17, 2022. Subscribe to eNews to receive all the articles in this series.

A good deal has been written about James Joyce’s father, John Stanislaus Joyce (1849–1931), but rather less has been said about his mother, Mary Jane Joyce (née Murray, 1859–1903). This vivid and lengthy letter, sent to James Joyce in Paris, gives a deep sense of the connection and trust that existed between Joyce and his mother. It also gives a sense of Joyce’s family more generally. By 1903 James Joyce, born in 1882, was the eldest of nine. The letter mentions six of his siblings: Stannie, Charlie, May, Mabel, Florrie, and Poppie (but omits Eva and Eileen).

Determined to study medicine and to earn a supplementary income from writing, Joyce had left Dublin to live in Paris on December 1, 1902, and remained there, apart from a visit home for Christmas, until April 12, 1903. During that period, Joyce wrote to different members of his family quite frequently, and some of their responses survive—a little archive documenting the network of emotional ties and bonds within the family.

This letter stands out for several reasons. It communicates a sense of how Joyce’s mother held the family together and of the high regard she had for James, her eldest son. It is notably focussed on practical issues and includes cash to pay the landlady, advice on getting started in journalism, an undertaking to get a suit cleaned, and prayers for Joyce’s “spiritual and temporal welfare.” The style is particularly endearing. Mary Joyce, known as May within the family, writes with little punctuation and describes herself as “simply talking just as we would do at the fire here.” This must have been some solace to her son, who was struggling to find home comforts (like food, heating and company).

“You cannot get on in your line without friends,” she writes, with underlining for emphasis. This plangent line seems to foretell some of the bitter arguments which characterized and dogged Joyce’s authorial career. May Joyce did not live to see those arguments unfold or her son’s success and worldwide renown. Just five weeks after this letter was written, Joyce received an urgent telegram from his father calling him home. “Mother dying come home Father,” it said, if the testimony of Ulysses as autobiography is to be believed.

Aged 44, May Joyce died just four months later, surrounded by family members. Joyce was just 21 and was bitter and angry about the circumstances of her death. He told Nora Barnacle, whom he met the following year: “My mother was slowly killed, I think, by my father’s ill-treatment, by years of trouble, and by my cynical frankness of conduct. When I looked on her face as she lay in her coffin—a face grey and wasted with cancer—I understood that I was looking on the face of a victim and I cursed the system which had made her a victim.”

Nine children may seem like a large family. May Joyce’s full birth history is more extreme. Between 1880 and 1897 there seem to have been six other pregnancies which ended in either infant death, stillbirth or miscarriage. This equates to one pregnancy a year. As the eldest surviving child Joyce must have been aware of this. Ulysses is notably sensitive to patterns of birth. Leopold Bloom, for example, thinks a good deal about what his emotional life and marriage might have been like “if little Rudy had lived.”

Joyce’s mother, like Stephen’s in Ulysses, might be seen as “a poor soul gone to heaven” who had “saved him from being trampled underfoot.” But it cannot be said that she died “scarcely having been.” As this letter shows, May Joyce was a vivid presence in the life of her eldest son, and was, for a time, the center of his emotional world. Her unstinting belief in him was formative for his creative self-confidence. Her premature death hardened his determination to succeed and served him with a depth of emotional experience which he could immediately draw on in his writing.

Joyce did not ordinarily keep personal correspondence because he moved so frequently. But, somehow, he kept hold of this letter. A tiny fragment of a rich and complicated life, the letter points to Joyce’s mother’s significance in his formation, and to the fundamental correlation between Joyce’s own life and the lives depicted in Ulysses.