Harry Ransom Center Book Collection

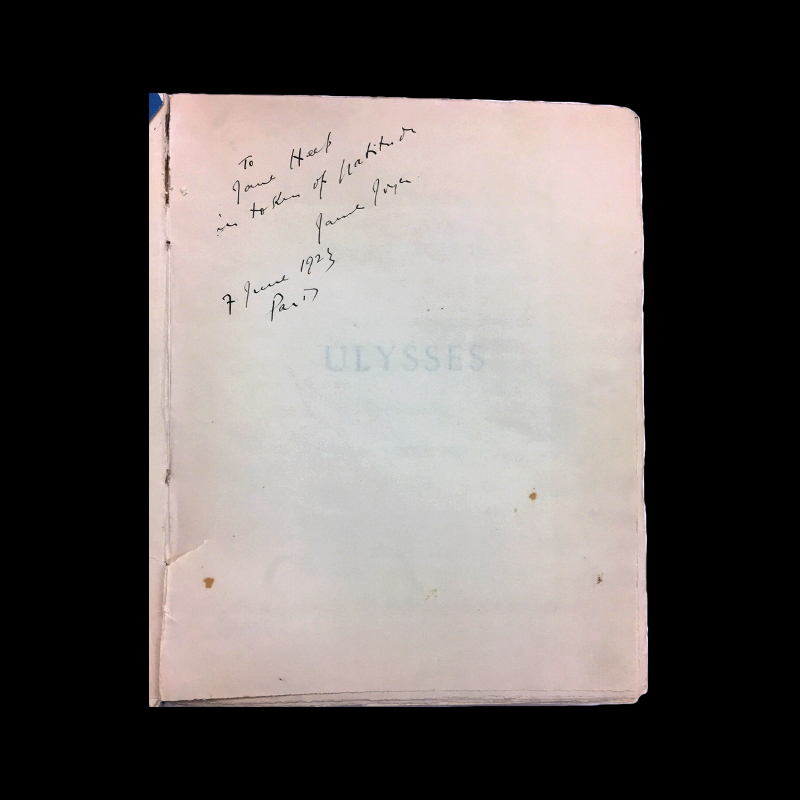

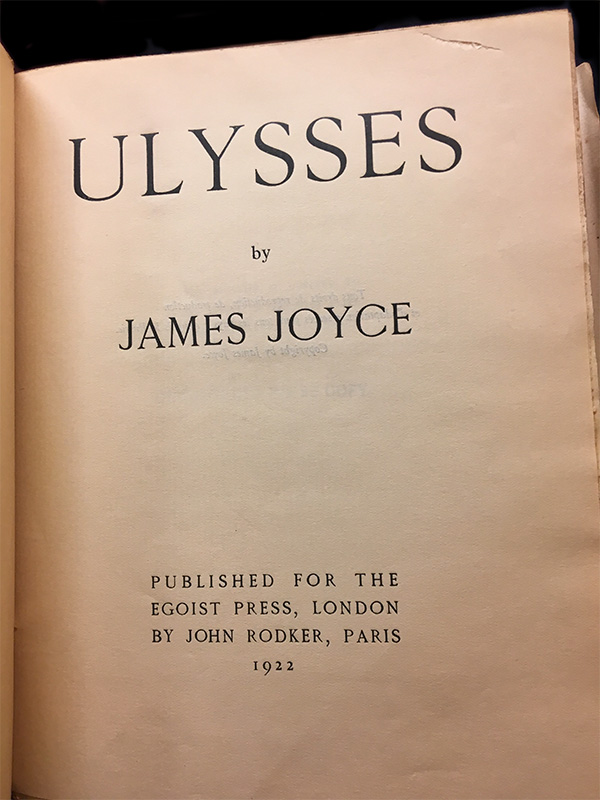

#6: James Joyce’s Ulysses (Published for the Egoist Press, London, by John Rodker, Paris,1922), inscribed by Joyce for Jane Heap

by CLARE HUTTON

This is the sixth article in a series devoted to objects that tell the story of women who supported author James Joyce and the publication of his landmark novel, Ulysses (1922). Learn more in the exhibition, Women and the Making of Joyce’s Ulysses, curated by Dr. Clare Hutton and on view through July 17, 2022. Subscribe to eNews to receive all the articles in this series.

Jane Heap worked tirelessly to ensure that Ulysses appeared regularly in The Little Review between March 1918 and December 1920. In New York, in February 1921, she stood trial alongside Margaret Anderson for the offence of publishing the final part of Ulysses, chapter 13 (“Nausicaa”). She was deemed guilty of publishing an “obscene” text, finger-printed, and fined $50. Joyce therefore had reason to inscribe this copy of Ulysses “in token of gratitude” on Heap’s first trip to Paris, and their first meeting in person, in 1923.

It is not clear what Heap and Joyce really made of each other. The published and unpublished correspondence leaves no record, and Joyce did not even know who Heap was when she first wrote to him on January 9, 1920, to explain that she felt The Little Review was “making an audience for your work.” Archival evidence suggests that it was Heap, not Anderson, who did the lion’s share of the considerable work involved in getting the content of The Little Review through press and mailed to subscribers. Anderson could be antagonistic and disengaged, and Heap was often left with the practical tasks of working with the printer, attending “to the door and telephone” and scraping together the money needed to pay for paper, postage, and printing.

Of the women associated with the publishing of Ulysses, Heap is the most difficult to get to know. Her absence from the record stems, initially at least, from the fact that her writing is either unsigned, or only signed with italicized lower-case initials—jh—as though to emphasize in typographical language the insignificance of her role, and to conceal her gender and identity more generally. As editor of the “Reader Critic” column in The Little Review that published the responses of readers to Ulysses as it was being serialized, Heap defended Joyce on multiple occasions, telling readers firmly that Joyce “has no concern with audiences and their demands.”

Even before the case against The Little Review came to trial, Heap published “Art and the Law,” a pre-emptive defence that pointed to the “heavy farce and sad futility” of “trying a creative work in a court of law.” However, with respect to the specifics of Leopold Bloom’s activity on Sandymount Strand, Heap skirts the issue of its specificity. She claims not to understand “Obscenity” and suggests that “Girls lean back everywhere, showing lace and silk stockings; wear low cut sleeveless gowns, breathless bathing suits; men think thoughts and have emotions about these things everywhere—seldom as delicately and imaginatively as Mr. Bloom.” What she sees in Bloom is “unpreventable” and “unfocused sex thoughts.” Heap knew there was more to the fireworks but turned a blind eye, given that the matter was sub judice. Joyce may not have been aware of Heap’s defence, which is ultimately also a plea for more openness about sexuality, and particularly better education for “young girls” beyond what is characterized as “a few obstetric mutterings.”

In addition to Anderson, Heap’s other female lovers included Florence Reynolds, Djuna Barnes, and Elspeth Champcommunal, the editor of Vogue. Joyce appeared not to notice that Heap was gay and did not make any comment on the blatant homophobia expressed by John Quinn, who defended The Little Review in the Ulysses trial of February 1921. Heap was one among a circle of gay women who supported Ulysses (others include Margaret Anderson, Sylvia Beach, and Adrienne Monnier). That they did so can be attributed to a belief in the power of Joyce’s vision, a willingness to engage in championing libertarian causes, a collective desire for greater candour about sexual preferences and sexual experience, and broad support for the fight against censorship.

“In token of gratitude” is the exact phrase Joyce used to inscribe his number 1 copy of Ulysses to Harriet Weaver, a prized object now on display at the Museum of Literature Ireland in Dublin. It is interesting to see Joyce using the phrase again in inscribing this copy for Heap. This is the Egoist edition of Ulysses, published by John Rodker in Paris for Weaver in London in October 1922. It is therefore an association copy in several senses, and points to the nexus of feminine material support which Joyce’s Ulysses was so fortunate to secure.