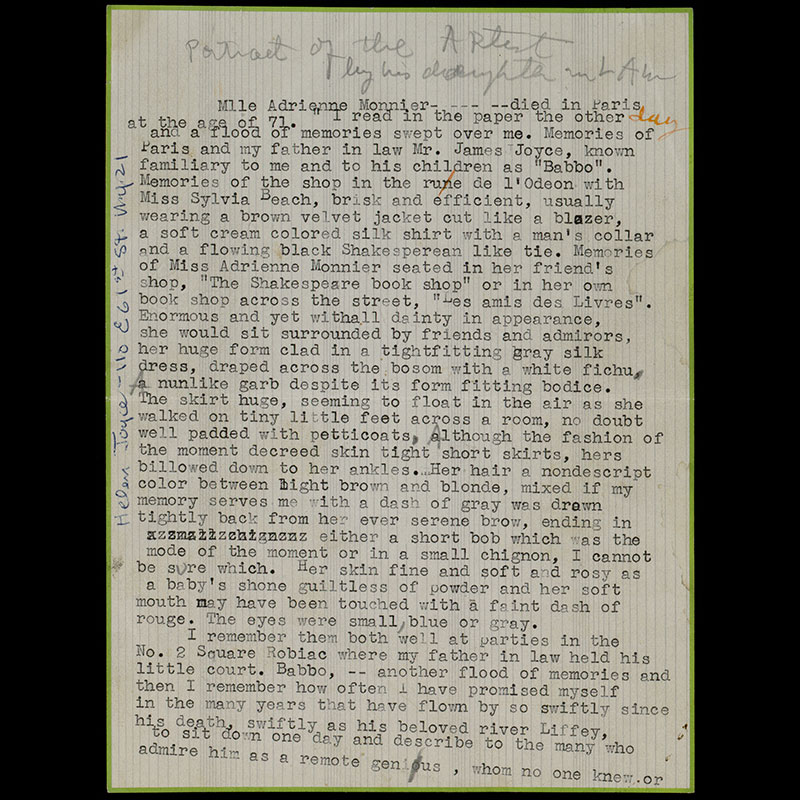

#9: A single page from Helen Joyce’s “Portrait of the Artist by his Daughter-in-law,” begun in 1955. James Joyce Collection, Harry Ransom Center, 7.3

by CLARE HUTTON

This is the ninth article in a series devoted to objects that tell the story of women who supported author James Joyce and the publication of his landmark novel, Ulysses (1922). Learn more in the exhibition, Women and the Making of Joyce’s Ulysses, curated by Dr. Clare Hutton and on view through July 17, 2022. Subscribe to eNews to receive all the articles in this series.

In chapter 9 of Ulysses when Haines asks Buck Mulligan whether Stephen Dedalus has written anything “for your movement,” Mulligan responds with derision, saying that Dedalus is “going to write something in ten years.” Writing is something that can always be put off, and writers who commit to writing regularly and for publication are the exception not the rule. Writing is difficult, after all. Difficult, but necessary: particularly if you want certain things to be remembered.

Helen Kastor Fleischman (1894–1963) married Giorgio Joyce, Joyce’s son, on December 10, 1930. She was more than 10 years older than Giorgio and the marriage did not last, following her nervous breakdowns in 1938 and 1939. In the intervening years there were, however, many happy moments, particularly with Giorgio’s parents, and these are remembered here, in an unpublished typed memoir begun after seeing an obituary notice for Adrienne Monnier, who died in June 1955.

The memoir begins by evoking the atmosphere and personalities of the rue de l’Odeon, where Adrienne Monnier ran La Maison des Amis des Livres and Sylvia Beach ran Shakespeare and Company. Helen Joyce made Joyce’s acquaintance while dining out with her first husband and remembers an evening of drinking and casual chitchat. Before long she had become a regular visitor to tea in the Joyces’ apartment, a “pleasant and informal affair” served by Nora while “Babbo” (as he was known within the family) “sat in his favorite chair”.

Evening parties tended to be rather wilder, and were attended by “the Stuart Gilberts, the Eugene Jolas’s, Sam Beckett, McGreevy” and so on. With whiskey and cognac flowing, there would be singing and dancing, and “old melodies” played at the upright piano, with everyone joining in. Sylvia Beach and Adrienne Monnier did not fit in easily at these parties, and Harriet Weaver, “a small and mousey woman of indeterminate age,” appears to have found them particularly trying. Her annual or bi-annual trips to Paris were dreaded by the family, if this account is to be believed.

Helen Joyce was aware that Weaver “had turned over a huge fortune” to Joyce and noted that “the best tea service” was brought into play on the occasion of her visits, when she would “insinuate herself into the life of the Joyces.” “Miss Weaver would be staying at some obscure little Hotel” and “would appear promptly at four every afternoon,” and opted not to dine “in the restaurants that the Joyces frequented.” Little details like this, the stock-in-trade of memoir writing, help to fill out a sense of Joyce’s world, and the separation he maintained between the women who helped him as a writer, and those with whom he preferred to socialize.

Memoir is a particularly important component in the evidence needed to write biography. Aside from Weaver, three other women were particularly important for the first publication of Ulysses: Margaret Anderson, Sylvia Beach, and Jane Heap. Anderson was the first to write her account. Her My Thirty Years’ War appeared in 1930 and is full of facts and opinions about Joyce and The Little Review. Beach struggled to write her memoirs which she began to commit to paper as early as 1927. Shakespeare and Company, her account of her business and relationship with Joyce, was published in 1959. Neither Heap nor Weaver ever wrote an account of their encounters with James Joyce, an absence which has shaped biographies and existing criticism.

The absence of memoir is only part of the issue. Joyce appears not to have kept the correspondence which he received from the many women who supported him. By contrast, there’s a significant archive of Joyce’s correspondence. A feminist approach to Joycean biography needs to attend to the skewed and imbalanced nature of the evidence, and work out how to appropriately recover the achievements and significance of women that are all too easy to forget.