Do you ever look at old photos and wonder what it would be like to take the photo, or to be in the photo? Would there be blinding lights? A stiff pose held for uncomfortably long? Was smiling allowed?

I recently sat for a modern tintype photo at Lumiere Tintype here in Austin. Tintypes were a popular format from the 1860s through the early 20th century. A tintype is made with light-sensitive silver media in a wet collodion binder on a plate of tin or another metal. Tintypes were created formally in the studio or casually on the street. Oftentimes, they were varnished to protect the image.

Tintypes are not created from a film negative; they are one-of-a-kind. The camera must physically hold the photo plate during exposure, and that can mean a big camera! Here’s the camera at Lumiere. The back of the camera is where the photographer inserts the plate.

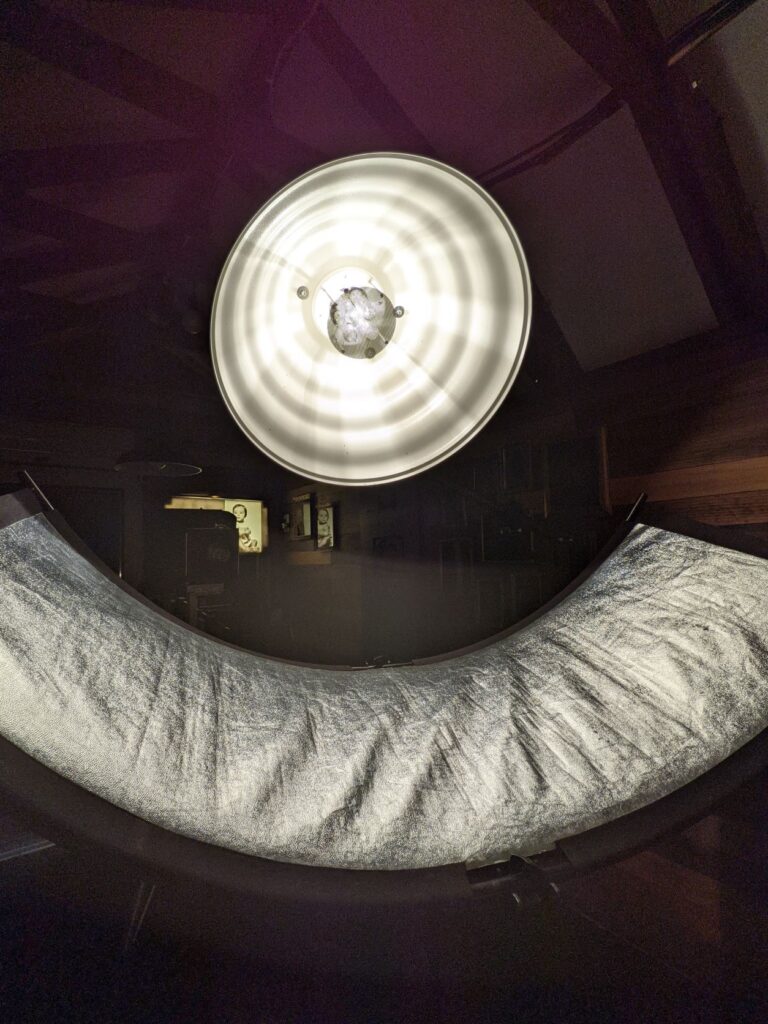

A tintype does require a lot of light, either through a long exposure or a bright blast. Here’s where I stood during my session, with a large reflector positioned just out of the frame. The exposure time was short, but the flash rattled my brain a bit.

The idea that historical photo processes took a long time is overgeneralized and not always correct. Photographer Adrian Whipp prepared my photo plate while I waited, and then moved quickly to shoot the photo in about five minutes. Afterwards, he demonstrated rinsing the image with sodium thiosulfate fixer, which dissolves away unexposed silver salts.

Last, Whipp applies a shellac-based resin varnish. High relative humidity can create streaks and bubbles in shellac, so he works in a closed space with a dehumidifier to apply this protective coating.

Finally, here is the result. Smiles are, in fact, allowed.