Lucy Prebble’s ENRON examines the fall of the Houston-based energy giant – but what happens when roles traditionally cast as men, are presented by a cast of female and non-binary actors? Artistic engagement strategist, Jess O’Rear and director, Hannah Wolf discuss the importance of casting, gender, power and toxic masculinity in Texas Theatre and Dance’s production of ENRON.

“In the late 19th century, a few notable actresses took on the roles of Shakespeare’s leading men in performances that impressed and scandalized critics in equal measure,” explains Jess O’Rear, a Ph.D. in Performance as Public Practice candidate and the artistic engagement strategist for ENRON. “Sarah Bernhardt’s Hamlet and Charlotte Cushman’s Romeo were praised for tapping into depths of emotion that, at the time, would have been considered improper for a man to display in public – the boys’ wild, lashing emotions, their longing and heartache. At the same time, Bernhardt and Cushman were criticized for taking on these “breeches roles,” accused of using the performance to show off their bodies in tights (hence the term).”

“What critics identified in these performances, perhaps unbeknownst to them at the time, was the performative nature of gender expression. Seeing and believing a woman playing a role such as ‘Romeo’ or ‘Hamlet,’ considered to be two of the most coveted roles for men, reveals that masculinity can be executed convincingly without the biological pre-requisites associated with manhood. To put it simply: if a woman can portray a man on stage with the same, if not more, success as a man, what is to say that she couldn’t do the very same thing in life? What does that mean for the concept of masculinity, or gender as a whole?

What does this mean, also, for the knowledge and power that people who are not men can wield? Critics reduced Bernhardt’s and Cushman’s performances to superficial attempts at drawing attention to their bodies for titillation. Skilled performances of relatable, believable masculinity by talented women were accused of being scandalous spectacles of impropriety. This seems a narrative not unknown to us today – women on the red carpet being asked about the designers of their dresses, instead of the emotional depth of the performance for which they are being honored.

How can we see this reactionary impulse by critics as a subtle sign of a power shift? A woman is on stage performing such a believable Romeo that some thought they’d never want to see a man in the role again – a Romeo so convincing, a performance so strong, that the sight of the actress’s ankles did not, for many audience members, detract from her performance at all. The actress does not have to hide herself in order for Romeo to be believable – and so what does that mean for the man who watches her and feels out-manned?

This is one of the ways in which theater is dangerous. By “dangerous,” I don’t mean harmful or violent. The danger of theater is the light that it sheds on the parts of us and our society which are so often hidden in shadow – a light that can reveal either a beauty often overlooked or an insidious menace.

In this production of ENRON, the talented women and non-binary performers reveal to us the artifice of the connection between maleness and masculinity assumed to be inextricable by our culture. The reverence paid to men who embody the harmful ideals of American masculine identity – greed, violence, ruthless competition, unstoppable arrogance – is indicted by the performance of these traits by actors who are assumed by hegemonic standards to be outsiders to this world.”

We spoke to Hannah Wolf, M.F.A. in Directing candidate and director of ENRON, about the choice to cast traditionally male roles as female and non-binary actors and the ways that choice lends itself to a better understanding of masculinity, power and gender.

“The idea for casting all women and non-binary actors in ENRON has been the root of this production since pitching it in October 2016,” explains Wolf. “With each turn in the news cycle, this casting concept and production becomes more and more relevant. This play has been historically cast with an ensemble of mostly white, cisgender men, but our production at UT is opening up a deeper conversation about power and toxic masculinity by casting an ensemble of performers who are not white cisgender men. This non-traditional casting asks the audience to question the links between power, toxic masculinity and big business. I believe that we can no longer talk about power without talking about gender and race. Our production seeks to critique the holders of unearned power and asks the audience to question role of toxic masculinity in our ‘too big to fail’ business culture.

The majority of the characters in the show are male, which was typical for the corporate sector in 90s (as well as today). The play takes us through their deceits and mistakes in attempting to game the system. I don’t know about you, but I’m sick of watching stories of powerful white men who destroy others for their own gain, especially when those stories don’t examine the core of the drive for more. Why do we automatically accept white men in positions of power and why do we accept tactics of toxic masculinity as success?

There is a sea change right now, as toxic masculinity is being more readily recognized and called out. I don’t think that there is anyone, regardless of gender, who can state that their life hasn’t been affected by toxic masculinity in some way. I believe that seeing the traits of toxic masculinity in the hands of performers who aren’t immediately recognized as power-holders allows the audience to identify these harmful characteristics. I question what attributes our society deems as ‘successful’ and how those fit onto men who are high on toxic masculinity. In this production, we cannot dismiss the actions of these men simply because ‘boys will be boys.’

In subverting the historical record and keeping the actors at an arm’s length from their characters, I hope that the audience will be able to look at the big picture of this story. ENRON infamously flopped on Broadway in 2010 because it was ‘too close to home.’ Now that ‘too big to fail’ corporate collapse is a common occurrence, it’s my desire that through holding the story and the characters at a distance, the audience will be able to see themselves in the traits of this system.

There is an undeniable power in this cast of 20. In giving powerful roles to people who don’t usually get them, these actors become the ‘authors of critique.’ This is a process of learning to take up space and allowing themselves to be seen and heard.”

ENRON

February 21-March 4, 2018

Oscar G. Brockett Theatre

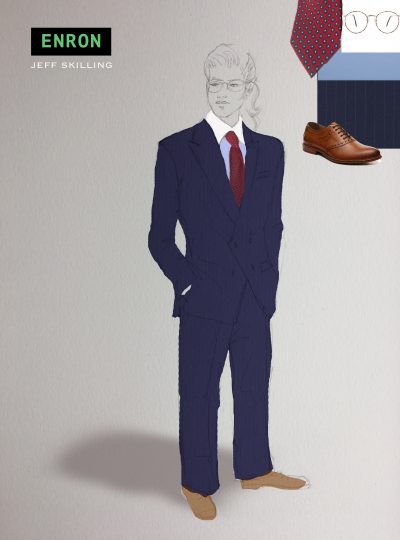

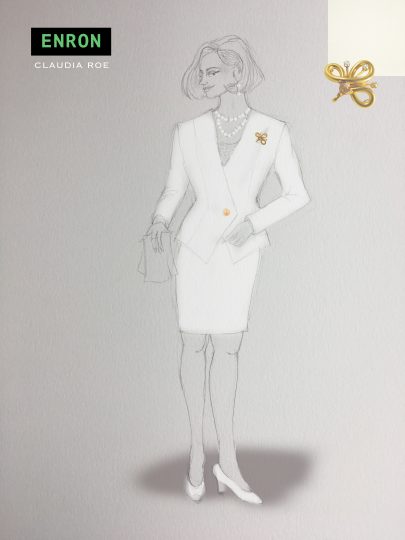

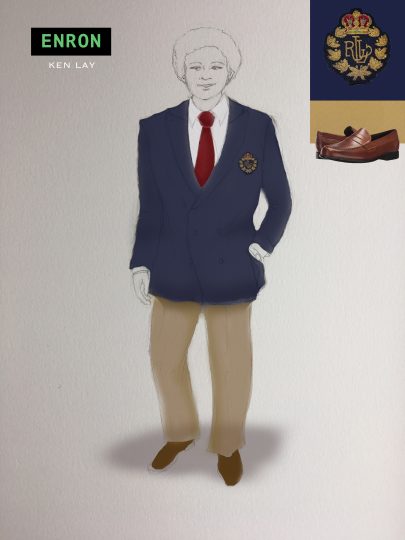

Photography by Lawrence Peart; Costume design renderings by Cait Graham.