The European Union (EU) has a well-regulated market for wildlife hunting trophies and live wildlife trade, but there are some loopholes that allow increased wildlife trafficking to enter the EU. Therefore, the EU is reviewing its regulation to combat trafficking. This reform process might influence the global status quo on wildlife trade and conservation since the EU, like the US, is one of the major players in the CITES regime and domestic regulations have spillovers worldwide. This article gives an overview on how EU wildlife trade regulation works, which are the main agents, what are the problems, and the changes foreseen. EU WILDLIFE TRADE REGULATIONS All EU member states ratified the Convention on International Trade of Endangered Species (CITES) and in 1984 the EU approved the core regulation of the EU Wildlife Trade Regulations that replicates the CITES system of permits for wildlife trade. The Council Regulation (EC) No 338/97 on the protection of species of wild fauna and flora by regulating trade thereinspecifies the rules for importing, exporting and re-exporting wildlife, for intra-EU trade and for movement of live specimens. It creates procedures and obligations for Member States and designs sanctions in case of infringements.

The Council Regulation is developed in the Commission Regulation (EC) No 865/2006 of 4 May 2006 laying down detailed rules concerning the implementation of Council Regulation (EC) No 338/97 on the protection of species of wild fauna and flora by regulating trade therein and it is amended by the Commission Regulation (EU) No 1158/2012 in order to include in the EU system species incorporated in CITES.

The Regulations create the Committee on Trade in Wild Fauna and Flora, the Scientific Review Group and the Enforcement Group that are chaired by the European Commission and attended by representatives of Member States’ CITES Management Authority. These bodies aim to coordinate Member States duties to issue permits and control trade; they can advise and even ban trade on species that are consider endangered. However, the lack of a single authority in the EU creates coordination and contradictions that make it more difficult to prosecute wildlife trafficking persecution. To diminish these problems, the EU implemented a system for information exchange to EUTWIX (Trade in Wildlife Information eXchange) since 2005.

Like the US Endangered Species Act and CITES, the EU wildlife trade regulation listed species in four annexes (A, B, C and D) regarding their level of protection. Member state Management Authorities issue trade permits in cooperation with their own national Scientific Authority. Like CITES Annex I-listed species, Annex A specimens cannot be imported for commercial purposes and require an import permit if they are personal items such as hunting trophies. Annex B specimens have a stronger protection than Annex II CITES-listed. The table below summarises the overlap between CITES and the EU regulations.

Permits are required to import Annex A and B-listed species; export Annex A, B and C-listed species; or re-export Annex A, B and C-listed species. Moreover, the EU certifies that the trade of animal or plants does not create any health risk, under the Council Regulation (EC) No 338/97 and Commission Regulation (EC) No 865/2006. In general terms, an import permit is issued only if there is no risk to conservation of the specie, the imported specimen was legally obtained, the accommodation is adequate for live animal specimen, the EU Commission has not published an import restriction, and the Scientific Authority has not given a negative opinion on the risk of importation for the species. For species in transit in the EU, Member States Management Authorities have to check that the species has the required CITES-export permit, but the EU does not issue any permit or certificate (Art 7.2 of the Council Regulation 338/97). The follow diagrams illustrate the procedure to import and export specimen of species listed in Annex A and B.

CHANGES IN THE EU WILDLIFE TRADE REGULATIONS In July 2013, the Commission opened a consultation process to revise “the EU rules governing trade in hunting trophies in species included in Annex B of Regulation 338/97.” In that document the European Commission recognized one of the major problems of the EU system:

import of hunting trophies of Annex B specimens into the EU is not conditional upon the presentation of an import permit delivered by the importing country. EU residents introducing into the EU for the first time a hunting trophy of an Annex B specimens are only required to present to Customs a CITES export permit issued by a third country.

This implies that national and European authorities have no registration of Annex B hunting trophies, reducing efficiency in the global efforts to conserve wildlife. For example, rhino horns have been entering the EU as hunting trophies without an import permit from the EU, since they were listed in Annex B. But afterwards, those horns have entered the illegal market, contributing to the growing poaching of rhino in Africa, jeopardizing the role of hunting as a positive instrument for global wildlife conservation.

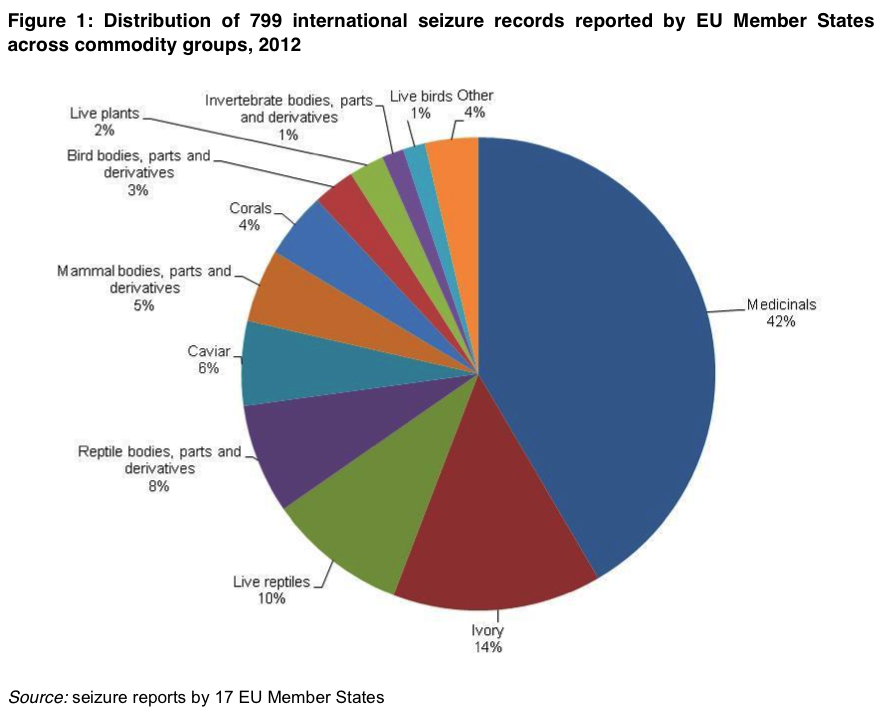

The EU reacted by modifying the rules for hunting trophies in 2014, banning importation of certain hunting trophies and listing other species in Annex A in order to request import permits. In January 2014, the European Parliament passed the European Parliament resolution on wildlife crime (2013/2747(RSP)) asking the “Commission to establish without delay an EU plan of action against wildlife crime and trafficking, including clear deliverables and timelines” (art 1). The resolution calls on the Commission to further strengthen the fight against wildlife trafficking within CITES and demands Member States to implement a system of penalties for prosecuting crimes against wildlife. The European Parliament based its demands on the evidence provided by the TRAFFIC 2013 report on EU trafficking. The report indicates that in terms of numbers of seizure records, the main types of commodity seized at EU borders in 2012 were wildlife for medicinal purpose, rhino horns (over 3500kg), ivory (70kg), live reptiles (812 specimens), reptile bodies and derivatives (1629 specimens) and caviar (51kg). The report includes the follow figure summarizing the information:

Following the Parliament recommendations and given the evidence of wildlife trafficking in the EU, in February 2014, the European Commission launched its COMMUNICATION FROM THE COMMISSION TO THE COUNCIL AND THE EUROPEAN PARLIAMENT on the EU Approach against Wildlife Trafficking. The communication recognises the UN definition of wildlife trafficking as “serious organised crime” and the links with money laundering and fraud and calls for global action and states that:

The EU remains a major destination market for illegal wildlife products, with a significant demand notably for species which attract high prices on the black market. At the same time, the major ports and airports of the EU are important transit points for trafficking activities, in particular between Africa and Asia. Some 2500 seizures of wildlife products are made every year in the EU.

The communication opened a public consultation process between February and April 2014 where European citizens, public and private organizations and institutions could participate. The consultation asked whether the EU wildlife trade regulation is sufficient, if an action plan is needed, how the EU should cooperate to end wildlife trafficking and how the EU should contribute to peace and security, how to improve wildlife crime data and how to implement a more efficient system of penalties.

The consultation was answered by some national environmental ministries, by the CITES secretary, by the UN, by businesses associations, by research groups and by NGOs (including TRAFFIC, WWF and WCS). Now, the Commission is reviewing its policy framework. The European elections in May 2014 and the constitution of the new European Commission with new Commissioners might have delayed this process, but a new proposal should enter the European Parliament and Council in the following months.

The process is not over, but as a preliminary conclusion we can say that the global community (scientific community, environmentalists, policy makers and activists) should follow closely the EU process of modifying EU wildlife trade because if the process is done correctly, it can considerably diminish wildlife trafficking. In so doing EU policy can contribute to global wildlife conservation and may provoke changes in the US legislation or even in the CITES framework.

Leave a Reply