Sport hunting by definition reduces an endangered species’ population. However, if wildlife managers charge hunters a substantial fee and use the revenue to support the remaining species’ population, sport hunting may be justified as a conservation tool. An example of the successful implementation of sport hunting as a conservation tool occurred in the remote mountains of Pakistan. A rare mountain goat, the markhor, was brought back from the brink of extinction and has re-inhabited much of its original range.

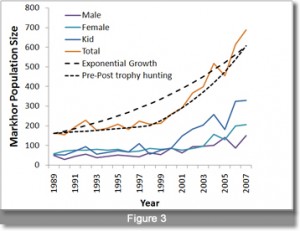

In 1984, political unrest, heavy artillery use and poaching nearly extinguished a key population of the wild goat living in the remote mountains of Pakistan. However, a community controlled conservation program that used limited trophy hunting to raise funds for markhor conservation succeeded in increasing the goats’ population from 200 to 3,500. In response and in an attempt to encourage U.S. hunters to contribute to the markhor conservation project, the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service reclassified the markhor from endangered to threatened and thus allows import of certain markhor hunting trophies. In the markhor’s case, a combination of variables convened to set the stage for the goat’s recovery: the local community actively supported and enforced hunting regulations, political unrest in the region subsided, the markhor range was remote, difficult to access, and limited, and conservationists used the hunting revenue to directly promote the markhor population. By changing the status of the markhor, the Fish and Wildlife Service (FWS) encouraged American hunters to pursue the goat, and the FWS was confident that American hunting expenditures were promoting the goat’s survival and the Pakistani conservation group was using American hunting revenue for conservation. A graph depicting the markhor’s population growth in the Chitral Gal region of Pakistan is below. Of note, following the implementation of a community based hunting conservation program in Chitral Gal in 1998 the markhor population has grown by nearly 12% a year.

The FWS can play a unique role in supporting foreign conservation efforts. By allowing hunting trophy imports, the FWS can play a unique role in encouraging American hunters to pursue certain species and thus support effective conservation programs. However, the FWS is also faced with a specific problem: determining which conservation programs are effective and honest.

In an effort to counter successful sport hunting conservation anecdotes, anti-hunting groups point to cases where unregulated hunting resulted in the extinction of a species, such as the tasmanian tiger. Some conservation programs are not effective and the fees charged hunters are not used for the conservation of the hunted species. In these events, American hunters can unwittingly contribute to the compromise of a species’ survival. Thus, the FWS must be deliberate and thorough in determining which trophies to allow hunters to import and which conservation efforts are supported.

To conclude, while studies and statistics support both sides of the argument, the current, available data is not sufficient to determine how much sport hunting revenue is used for wildlife conservation. Any attempt to determine the contribution of sport hunting revenue to conservation must address an individual species in a specific location. As in the markhor’s case, numerous variables, including location, community support, political unrest, and international demand determine the viability of sport hunting as a conservation tool.

Leave a Reply