“Is it ever OK to defend a policy that can mean the loss of human life in order to protect wildlife?”

Save the Rhino International poses this question in an informational piece on shoot-to-kill (S2K) policies, defined as a ranger’s right to fire back at poachers even if doing so endangers lives.

This question is overly simplistic and misleading.

It obfuscates the more truthful and important dimensions of S2K policies, mistakenly implying that loss of human life is effective at protecting wildlife. It also neglects the negative consequences, which extend beyond ‘externalities’ and into the realm of unethical policy.

Evaluating S2K requires justifying the loss of human life–an exercise in morality and efficacy. How does fear of arbitrary injury and death affect communities where S2K policies exist? How can we begin to quantify the costs of an increasingly militarized society in which poachers, rangers, and villagers back up their distrust of each other with poisoned arrows and automatic weapons?

Before we determine if the costs in human life justify the benefits of protecting wildlife, we must first assess if wildlife is benefitting from S2K policies in the first place.

Arguments for S2K

Save the Rhino recommends “shoot-to-kill only as a last act and in self-defence. Anti-poaching rangers must first do all they can to avoid this.” This stance strips S2K down to normal self-defense and does not represent the more militarized S2K policies practiced by some African and Asian range countries. At Kaziranga National Park in India, a ranger is awarded a cash bonus and guaranteed legal indemnity for each suspected poacher he kills—whether in self-defense or proactively. In October 2013, Tanzania’s tourism minister Khamis Kagasheki defended S2K policy with forceful language:

“The only way to solve [the poaching] problem is to execute the killers on the spot.”

Proponents of S2K cite several advantages to the policy:

- S2K policy can compensate for weak judicial systems, which are plagued by corruption, low conviction rates, and inadequate evidence.

Save the Rhino notes, “Time and time again, poachers are acquitted at trial.” In certain range countries such as South Africa, poachers are prone to recidivism when freedom can be exchanged for a small fee.

- S2K policy protects park rangers.

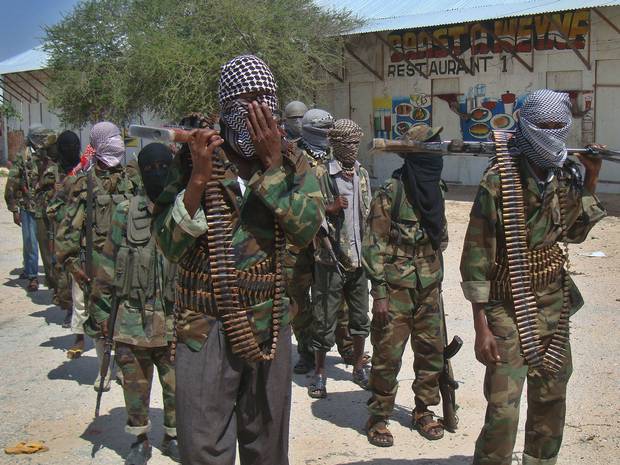

The Thin Green Line Foundation estimates that over 1,000 rangers have been killed on the job over the last decade. Rangers are likely facing increasing risk as militant groups like Al Shabaab and the Lord’s Resistance Army are using weapons with greater frequency and sophistication.

- Killing on the spot effectively protects rhino and elephant populations.

Fight for Rhinos, another rhino conservation nonprofit, poses a basic question: Does it work? The organization cites S2K policies in Swaziland, India, Zimbabwe, and Tanzania to demonstrate how S2K suppresses poaching to remarkably low levels.

Does S2K Work?

Swaziland’s Big Game Parks is often cited as a successful model for anti-poaching efforts. Ted Reilly, who led efforts to establish Swaziland’s first wildlife sanctuaries and reintroduce 22 large animal species into the wild, supports the shoot-to-kill policy integrated into Swaziland’s Game Act. He prescribes to the ‘war on poaching’ mentality and states, “We prefer not to put people in jail and we want to keep our rhinos alive. People say our law is draconian, but it’s worked.” It is true that Swaziland has lost a much smaller percentage of its rhino population to poaching than neighboring South Africa—where rangers are not automatically granted indemnity for killings.

However, it would be myopic to attribute Swaziland’s success solely to shoot-to-kill policy—a fact that even Ted Reilly admits. The Game Act also establishes a minimum jail sentence of 5 years and requires a convicted individual to pay back the value of a poached animal. Factors such as political will, harsher penalties, the absence of paramilitaries, and distinct socioeconomic factors are indivisible from the equation.

For example, when local socioeconomic factors are taken into account, we see that poachers and poaching vary throughout Africa and Asia. Michael Schwartz, consultant and freelance writer, asserts that the Kenyan ranger who wards off Al Shabaab militants is far removed from the South African ranger who is more likely dealing with “impoverished men simply trying to make a better living and feed their families.” Schwartz advocates education and rehabilitation along with poverty reduction as policies to stem poaching in South Africa. More generally, variation in conditions across regions, countries, and regimes suggests that conservationists and policymakers should vary their approaches.

Going one step further: should we attribute any success to S2K policies when there are other factors in play? Some argue that S2K policies clearly do not work in the long term and can exacerbate challenges and risks. Conservationist and author Robert Pierce emphasizes the need to reject a war mentality on poachers and poaching. He points out that Kenya intended to protect wildlife and promote tourism with an S2K policy, but poaching escalated and became harder to tackle as poachers adopted smarter methods to hunting animals and evading capture. As ivory becomes more dangerous to acquire, its price increases—solidifying a ‘vicious circle’ that draws in sophisticated criminal gangs, paramilitary groups, and poorer locals.

Others argue that the objective of rooting out poachers is futile as criminal gangs and paramilitaries are able to consistently replenish poaching teams as long as ivory remains a lucrative product. There is an additional risk that park rangers, lured by the high payout from poaching, can use their weapons and training to aid poachers or conduct poaching themselves. Heavily arming rangers can assist them in protecting themselves and animals on the job, but it also perversely alters the risk and incentive structures involved in poaching.

Lastly, Wendy Annecke of SANParks warns that “military ethos is a different ethos to conservation.” She asserts that militaristic policies such as S2K invite individuals with little wildlife appreciation into conservation and this influx necessarily harms the environment.

Beyond Practicality

The answer to ‘Does S2K policy work?’ remains murky and divided thus far. But investigation of how S2K policies work reveals that it imposes unacceptable costs on innocent civilians and societies. It becomes clear that S2K is morally indefensible and an unacceptable tool for governance.

To reiterate, S2K is not the same as self-defense. Proactively shooting a person with intent to kill, without proper evidence and trial, are antithetical to rule of law. In countries where the death penalty applies to murder and treason, government is still obligated to afford a trial. S2K policies cannot compensate for weak judicial systems when, in reality, they further erode any semblance of law.

A ‘war on poaching,’ fueled by increasingly weaponized and militarized anti-poaching tactics, side-steps fundamental civil rights and allows governments to promote arbitrary violence in a gloves-off manner. During Tanzania’s one-month, violent crackdown against poachers in October 2013, thirteen civilians were killed and more than 1,000 were arrested. First glance suggests an effective campaign: Fight for Rhinos finds the S2K policy “extremely effective” because only 2 elephants were killed that month. But the Tanzania case demonstrates the extreme moral and physical costs of S2K policies. It is more likely that pervasive fear and suffering disrupted poaching throughout the country just as they disrupted the daily lives of innocent civilians. An investigation conducted by Tanzanian officials reveals that innocent civilians were subjected to arbitrary murder, rape, torture, and extortion during this month of terror.

A similar story plays out in Swaziland where only three rhinos have been poached since 1992. Thuli Makama, Swazi lawyer and winner of a 2010 Goldman Environmental Prize, exposed extra-judicial killings and maiming that occur when rangers from private game reserves feel empowered to act beyond self-defense. She reports:

We are finding incidents where people are being pursued to their homes…[w]here people are taken from their houses and all sorts of things are done to them.

Exploring how shoot-to-kill policies ‘work’ exposes their human costs, which also debunks the idea that shoot-to-kill policies work at all. It is unacceptable to regard a policy as effective when—at best—animal lives are traded for human lives, when excessive and arbitrary violence is shielded from justice in the name of conservation. Poaching is a brutal and destructive activity, and shoot-to-kill policies simply extend this brutality and destruction onto local populations.

So, is it ever OK to defend a policy that can mean the loss of human life in order to protect wildlife?

The answer: Not when the policy is both unsustainable and unjust.

Leave a Reply