Policing ivory trafficking is hard for many reasons – but one of the biggest barriers is understanding the trafficking supply chain. In August of 2014, the Center for Advanced Defense Studies’ (C4ADS) published a report that helps frame how ivory trafficking works, including who is involved, how goods are moved and where they start and end up.

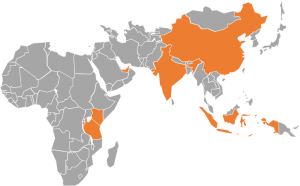

Like many trafficking operations, ivory traffickers have sophisticated logistical and operational capabilities and rely on either active or passive involvement of governmental officials. The global, sophisticated nature of this crime is underscored by the number of countries’ citizens, assets and/or territory that is involved in this incident, visible on the map below. It can be hard to understand how trafficking works from the outside, so I’ve summarized a particular “bust” highlighted in the report, with the goal of increasing appreciation for the challenges inherent in policing trafficking.

Map highlighting all countries involved in Mombasa ivory seizure in 2013.

The Ivory Seizure

C4ADS undertook an investigation of a January 15, 2013 Mombasa port seizure of over 3800 kg of ivory. Through their investigation of the actors, logistics, companies and routes that led to the seizure in Mombasa, C4ADS was able to reconstruct two important components of the ivory supply chain: 1) the supporting network that enabled the poaching and transit to the export port and 2) the path the shipment likely would have followed into Asia. The post-Africa part of the likely transit route was traced by other seizures of ivory and arrests of affiliated people along the way.

The January 2013 Mombasa seizure led to the arrests of two men, one of whom was allegedly linked to a seizure of ivory in Singapore eight days later. A third man was also implicated; he had previously been arrested on charges of smuggling ivory out of Mombasa into Bangkok, where it was seized. Individuals in the trade stay in the trade, even after arrest.

The shipping and logistics strategies reveal the sophistication of the actors involved. The ivory seized on January 13 was transported and trucked by a consignment company based in Mombasa that may or may not have known it was handling contraband. A Kenya-based company served as the clearing agent, despite not actually being registered as a Kenyan business. In fact, it was listed as a suspended clearing agent by the Kenyan revenue authority. Two different companies served as exporters – one based in Mombasa and the other in Nairobi. The consignees were Indonesian. Three different import companies were used, at least two of which were shell companies. This demonstrates that many business entities, whether registered or not, legal or illegal, are required in order to move goods.

The ship was owned by an Indian company, while the shipping line that would have been used if the seizure had not occurred is listed with a multinational container leasing company. The container leased for the January shipment was linked to another container that was seized in Hong Kong two months earlier. The same containers, consignees, transporter, clearing agents and exporters were all involved in that previous seizure.

The Hong Kong seizure originated in Dar es Salaam and traveled through Dubai before arriving in Hong Kong. Seven men were arrested in conjunction with the Hong Kong seizure. One man was a prominent Tanzanian businessman who served as Acting Managing Director of a trucking company that transported illicit copper from Zambia to Dar; the copper had been seized one year earlier in August 2011. He was acquitted, along with a politician who was a member of Tanzania’s ruling political party who was also involved.

Larger Trends

According to the research undertaken by C4ADS, this seizure is simply a single example of commonly conducted activities. Supporting evidence includes the volume of the trade in illegal ivory, the size of seizures along the trafficking supply chain and qualitative evidence from discussions with those involved in the trade.

Furthermore, during interviews with Washington-based government and non-governmental officials and experts, all observed that wildlife crime follows patterns observed in the trafficking of other illicit goods. The general idea conveyed in these interviews was that these sorts of trafficking practices are common and endemic to the trafficking of high value goods.

Other literature on trade routes also supports the findings in the C4ADS report and my interviews. Tom Milliken’s research reflects the same general pattern of illicit ivory leaving primarily African seaports and heading to Asian markets. However, he also notes that some of the ivory consignments bound for China are transited through Europe. A report resulting from the inter-agency cooperation of UNEP, CITES, IUCN and TRAFFIC similarly finds that most ivory is shipped in containers on ocean vessels from seaports in West and South Africa. The report also notes that smaller fishing vessels that travel from Africa to Asia may also be involved in smuggling ivory, though these types of vessels are not subject to inspection.

“… either active or passive involvement of governmental officials …” Like in India, in many parts of Africa the remuneration of officials, esp. lower rung civil servants, is calculated to be so frugal as to invite bribes to make a true living. The governments actually kind of invite (!) their staff “to live off the land”. However, once you change this and corruption already runs rampant in a country, the then higher wages for civil servants tend not to phase out the original corruption but replace it with nepotism, whereby the better paid positions go to political appointees and in the end entrenched oligarchies rule (similar developments bedeviled the Ebola campaign of the WHO where everyone knows that well-paid international assignments in UN affiliated organizations regularly go to the “well-connected” and not to those who understand the subject matter). These oligarchies tend to overlap with the traffickers in the human, arms and drug trade. You could really only change this with international involvement that would likely not be tolerated by these very national elites though. It still amazes me that there is such a thing as the “mani pulite” anti-Mafia police arm in Italy who risk their lives for measly pay. Something along those lines would have be be installed in these African countries (and the rain forest regions against illegal logging too).