The current debate about Confederate memorials in the United States highlights their importance in terms of current symbolic meaning, location, and original intent. The equestrian statue commemorating the conquistador Sebastián de Belalcázar (1479/80-1551) in Popayán, Colombia, can help us understand what these monuments signify today and why they have become objectionable.

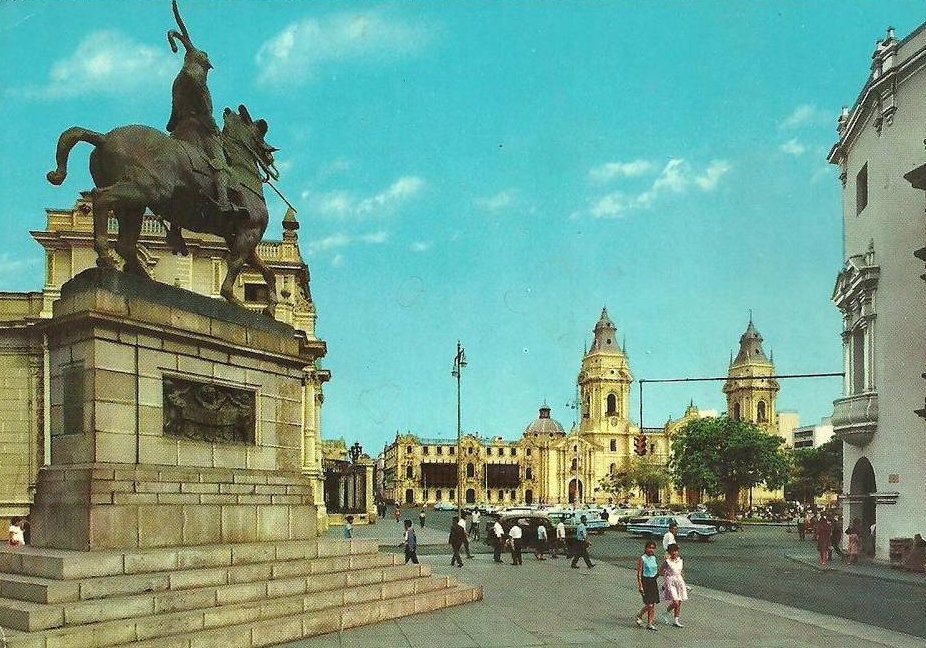

In Latin America, there are many statues in honor of liberators from Spanish colonial rule, like Simón Bolívar, José de San Martín, and others, just as there are monuments to George Washington and Thomas Jefferson in the United States. Colonizing powers are known to have erected monuments remembering colonizers, like the Columbus monument in San Juan, Puerto Rico, erected in 1893. However, there are also are a handful of statues commemorating conquistadors that were erected in the post-colonial period. Notable examples are the Columbus monument in Santo Domingo and the Pizarro monument in Lima, about which I wrote earlier. The Belalcázar monument in Popayán belongs to that list as well.

Sebastián de Belalcázar and his mercenaries arrived in Popayán in 1537, claimed the territory for the Spanish crown and founded the city of Popayán. Belalcázar already had founded the city of Quito, and he went on to found others, like Cali, and is considered a co-founder of the city of Bogotá. Creating colonial settlements was the most important method for the Spanish to establish control over newly subjugated territories. So why was the colonizer honored with a monument in 1937?

The Belalcázar monument was created by the Spanish sculptor Victorio Macho (1887-1966) in 1937 to commemorate the quadricentennial of Belalcázar’s conquest and the founding of the city of Popayán. It was first placed in the center of town in the Plazoleta de San Francisco. In 1940, it was moved to the top of the Morro de Tulcán, a hill ad the edge of the colonial core of Popayán that offers a great view of the city. The poet Rafael Maya (1897-1980), a member of the conservative and anti-modernist literary movement Los Nuevos, told Macha that the statue should symbolize Popayán’s best: “a heroic race, wisdom, beauty, holiness, poetry and song.” It is evident that the the statue was intended to celebrate hispanidad –that is an Iberian and Catholic identity with affinities to contemporaneous Spanish fascism.

El Morro del Tulcán is a poorly researched pre-hispanic pyramid, perhaps dating back to 500 CE, although some archeological finds point to use as late as the early colonial period. During road construction at the foot of the pyramid in 1928, adobe structures, vessels, bones and other pre-hispanic objects were found. When the top of the pyramid was removed to create a level space to place he equestrian statue of Sebastián de Belalcázar in 1940, it was well known that this was a sacred Indigenous site.

Thus the quadricentennial of the founding of Popayán only served as a nominal pretext to erect this equestrian statue. Its real purpose was to assert the rule of Colombians of Spanish descent over Indigenous Colombians. Placing the equestrian statue on top of a sacred pyramid was a conscious act of desecrating a native site, of staking a claim to the land, and of establishing cultural primacy. Only the amount of graffiti on the base of the monument seems to indicate that its placement is controversial in contemporary Colombia.

And herein lies the obvious connection with the Confederate monuments. They were mostly created between 1900 and 1920, decades after the end of the Civil War. Their purpose was not primarily to celebrate the accomplishment of the Confederate leaders but rather to reassert White supremacy in the Jim Crow South. Their intent was to put the White brand on public spaces and to intimidate Blacks. The point is not that the monuments of Sebastián de Belalcázar and Robert E. Lee might offend some people today. The critical point is that they were erected with the intent to offend and to intimidate.

PS: The Belalcázar monument in Popayán was toppled by an Indigenous group on 16 September 2020.